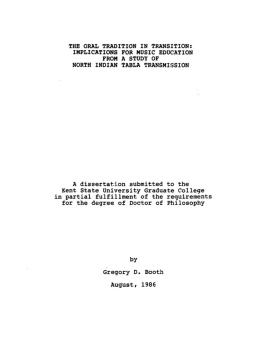

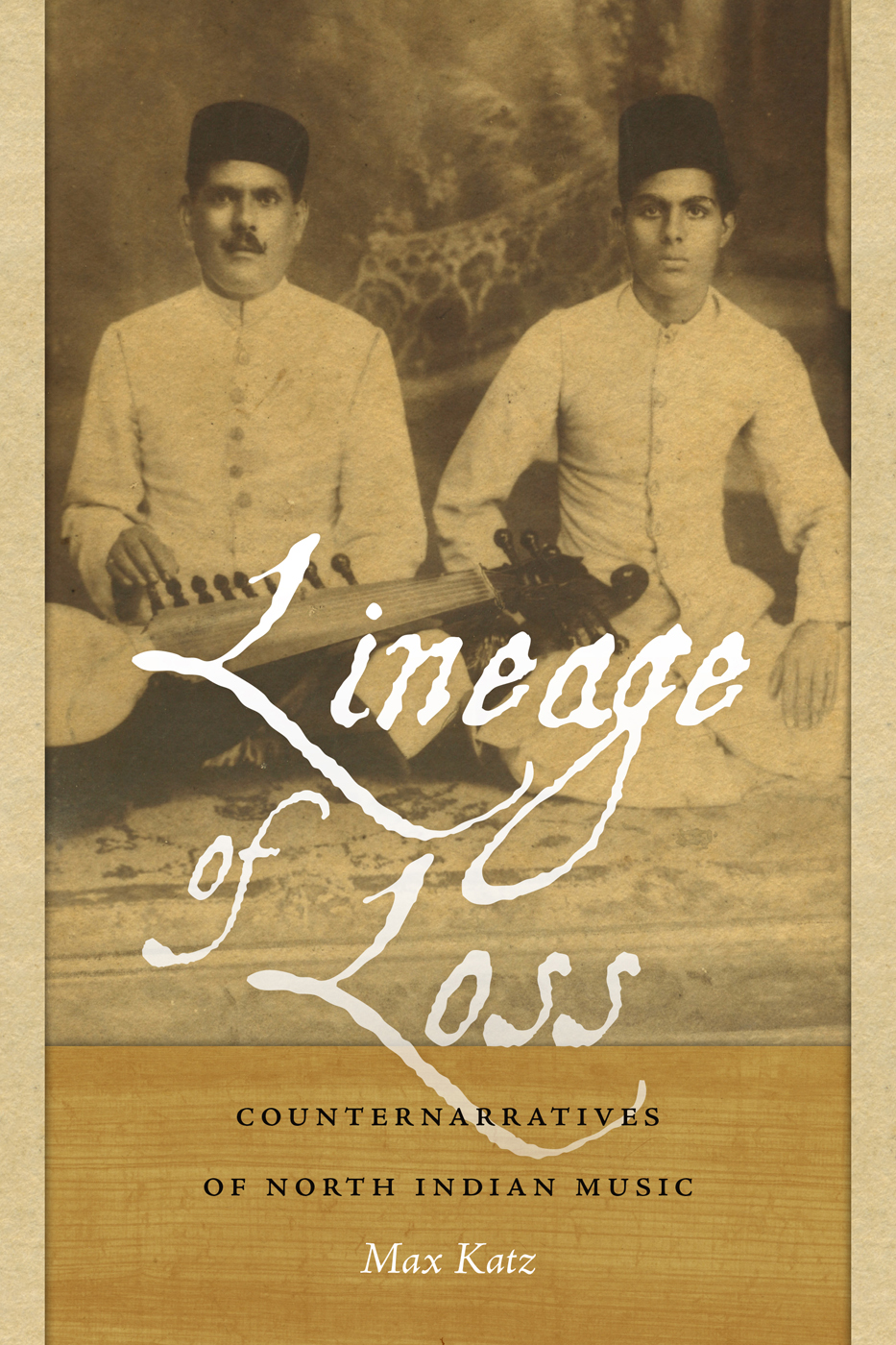

Lineage of Loss

Max Katz

LINEAGE OF LOSS

Counternarratives of North Indian Music

Wesleyan University PressMiddletown, Connecticut

Wesleyan University Press

Middletown CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2017 Max Katz

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by Mindy Basinger Hill

Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Sections of have been excerpted by permission of the Society for Ethnomusicology from my 2012 article Institutional Communalism in North Indian Classical Music, Ethnomusicology 56(2): 27998.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Katz, Max, 1976 author.

Title: Lineage of loss: counternarratives of North Indian music / Max Katz.

Description: Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, [2017] | Series: Music/culture | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2017019097 (print) | LCCN 2017031327 (ebook) | ISBN 9780819577603 (ebook) | ISBN 9780819577580 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780819577597 (pbk.: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Hindustani musicSocial aspectsIndiaHistory. | MusiciansIndia, NorthLineageHistory. | Hindustani musicIndiaLucknowHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML3917.14 (ebook) | LCC ML3917.14 K37 2017 (print) | DDC 780.954/5dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019097

54321

Front cover photo courtesy of Irfan Khan.

CONTENTS

A NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION

This book employs words from Hindi and Urdu, and to a lesser extent Sanskrit, Persian, and Arabic. In my approach to their transliteration, I have endeavored to strike a balance between the two potential extremes of pedantry and ambiguity. On one hand, it is important to me to present readers with enough information about a given word that they may understand its pronunciation and also its likely spelling should they choose to pursue reference materials. On the other hand, I would not like to overburden readers with excessive diacritical markings from multiple contrasting systems suited to the specific linguistic origins of various terms.

Thus, I have chosen to use only a select number of diacritical markings and to employ them as consistently as possible. To indicate long vowel sounds I have used the macron, as in ashrf and gt. For retroflex consonants I have used the underdot, as in humr and mukh. Nasalization is indicated with an n with an overdot, as in Bhairav and sagt. For fricative sounds I have used a single underline, as in ghazal and khyl. For accuracy of Sanskrit treatise titles, I have additionally marked the palatal s with an accent, as in Nradyaik and Nyastra; I have used the same for patently Sanskrit words such as ruti.

I have in most cases avoided the apostrophe or single open quotation mark often used to indicate Urdus ain because the letter does not carry the unique guttural sound in Urdu that it does in Persian and Arabic. Instead, in Urdu, the ain is most often pronounced as or a. It may also be silent or carry other vowel sounds, such as e, as in sher. For aspirated consonants I have used the single h, as in chuo and Jhinjho. This means, however, that the unaspirated ch is rendered with only a c, as in cc and cikr.

Some Hindi/Urdu words have become part of the English lexicon, for example chai, jungle, and verandah. I believe the word sitar is one of these, so I have not rendered it as sitr but instead left it in its familiar form. Likewise, for most names of individuals I have not included diacritical specifications. By contrast, some terms that occur throughout the text are rendered exclusively with diacritics (such as gharn and rga) but are italicized only on first appearance. My intention is to retain the emphasis on correct pronunciation without continually marking such words as foreign through the use of italics. Some words that appear infrequently in the book are italicized throughout, such as lp, mukh, and gat, which are Hindustani musicological terms: the consistent italicization of such terms marks them as part of a specific technical discourse that I enter in only a few sections of the book. Likewise, rga names remain italicized. For pluralization of transliterated words, I have used the -s as in humr-s and gharn-s. In quotations from previous authors, I have reproduced their own spelling, including their use or non-use of diacritics and italics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The book you hold in your hands is the result of fifteen years of training and research in ethnomusicology and Indian music, an undertaking inconceivable in the absence of countless teachers, guides, colleagues, interlocutors, and loved ones. Their generosity of spirit undergirds every page of this book. With inevitable and regretted omissions, I will attempt to express my gratitude here.

First and foremost I thank my principal scholarly preceptor, Professor Scott Marcus; his commitment to and faith in my work never waivered. I remain forever grateful to Professor Marcus, along with Professors Timothy Cooley, Dolores Hsu, George Lipsitz, and Bishnupriya Ghosh, the members of my doctoral committee at the University of CaliforniaSanta Barbara. I have been especially fortunate to receive feedback, support, and instruction from the broad and international community of senior scholars of Indian music. In particular, I have benefited from the guidance and encouragement of Regula Qureshi, Daniel Neuman, Bonnie Wade, Peter Manuel, James Kippen, Richard Widdess, Helen Myers, Stephen Slawek, Lakshmi Subramanian, Allyn Miner, Franoise Nalini Delvoye, and Brian Silver. I am further blessed to count among my friends, colleagues, and co-conspirators the brilliant Indian music scholars Katherine Schofield, Margaret Walker, Dard Neuman, Jayson Beaster-Jones, Shalini Ayyagari, Aditi Deo, Rumya Putcha, Anna Schultz, Bradley Shope, Anna Morcom, Kaley Mason, Stefan Fiol, Peter Kvetko, Niko Higgins, Meilu Ho, Sarah Morelli, Davesh Soneji, Amanda Weidman, Zoe Sherinian, Matthew Rahaim, and Justin Scarimbolo. The last twoMatty and Justinremain for me not only models of intellectual, musical, and personal integrity, but two of my closest and most cherished friends and confidants. Beyond the realm of Indian music, I have enjoyed the friendship of a number of fellow travelers along the path of ethnomusicology. In particular I thank Denise Gill, Kara Attrep, Lillie Gordon, Sonja Downing, Karen Liu, Ralph Lowi, Kathy Meizel, Eric Ederer, Gibb Schreffler, Revell Carr, Phil Murphy, Laith Ulaby, and Michael Iyanaga.

Over the years many friends and colleagues have given me the gift of close and careful critique of my work, including detailed commentary and numerous discussions that helped shape the present book. In particular, I owe heaping debts of gratitude to Justin Scarimbolo, Matthew Rahaim, Jonathan Glasser, Rob Wallace, Anne Rasmussen, Katherine Schofield, and Allyn Miner. I am likewise grateful to the anonymous reviewers who provided extensive responses to my book manuscript through both the Wesleyan University Press review process and my own tenure review. I am further grateful to the staff at Wesleyan University Press, including Parker Smathers, Suzanna Tamminen, Marla Zubel, and Jaclyn Wilson, and to Susan Abel of University Press of New England and Sara Evangelos. I thank the series editors of the Music/Culture Series of Wesleyan University Press: Deborah Wong, Sherrie Tucker, and especially Jeremy Wallach, who took a keen interest in my project and encouraged me to submit a proposal to the press.

Next page

![Katz - Zombie Slayer Box Set, Vol. 1 [Books 1-3]](/uploads/posts/book/141697/thumbs/katz-zombie-slayer-box-set-vol-1-books-1-3.jpg)