The book you are holding came about in a rather different way to most others. It was funded directly by readers through a new website: Unbound.

Unbound is the creation of three writers. We started the company because we believed there had to be a better deal for both writers and readers. On the Unbound website, authors share the ideas for the books they want to write directly with readers. If enough of you support the book by pledging for it in advance, we produce a beautifully bound special subscribers edition and distribute a regular edition and e-book wherever books are sold, in shops and online.

This new way of publishing is actually a very old idea (Samuel Johnson funded his dictionary this way). Were just using the internet to build each writer a network of patrons. Here, at the back of this book, youll find the names of all the people who made it happen.

Publishing in this way means readers are no longer just passive consumers of the books they buy, and authors are free to write the books they really want. They get a much fairer return too half the profits their books generate, rather than a tiny percentage of the cover price.

If youre not yet a subscriber, we hope that youll want to join our publishing revolution and have your name listed in one of our books in the future. To get you started, here is a 5 discount on your first pledge. Just visit unbound.com, make your pledge and type SATDV5 in the promo code box when you check out.

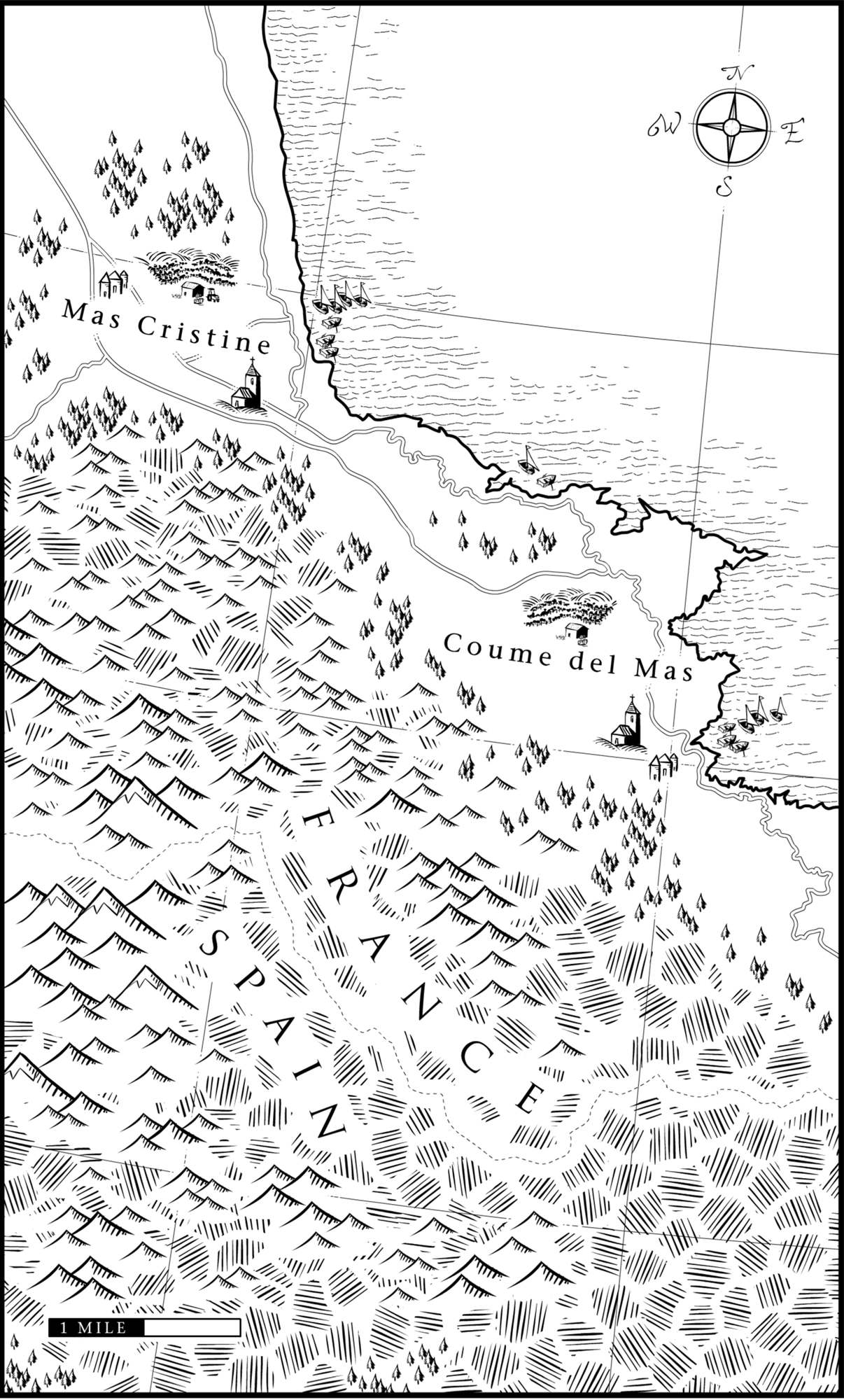

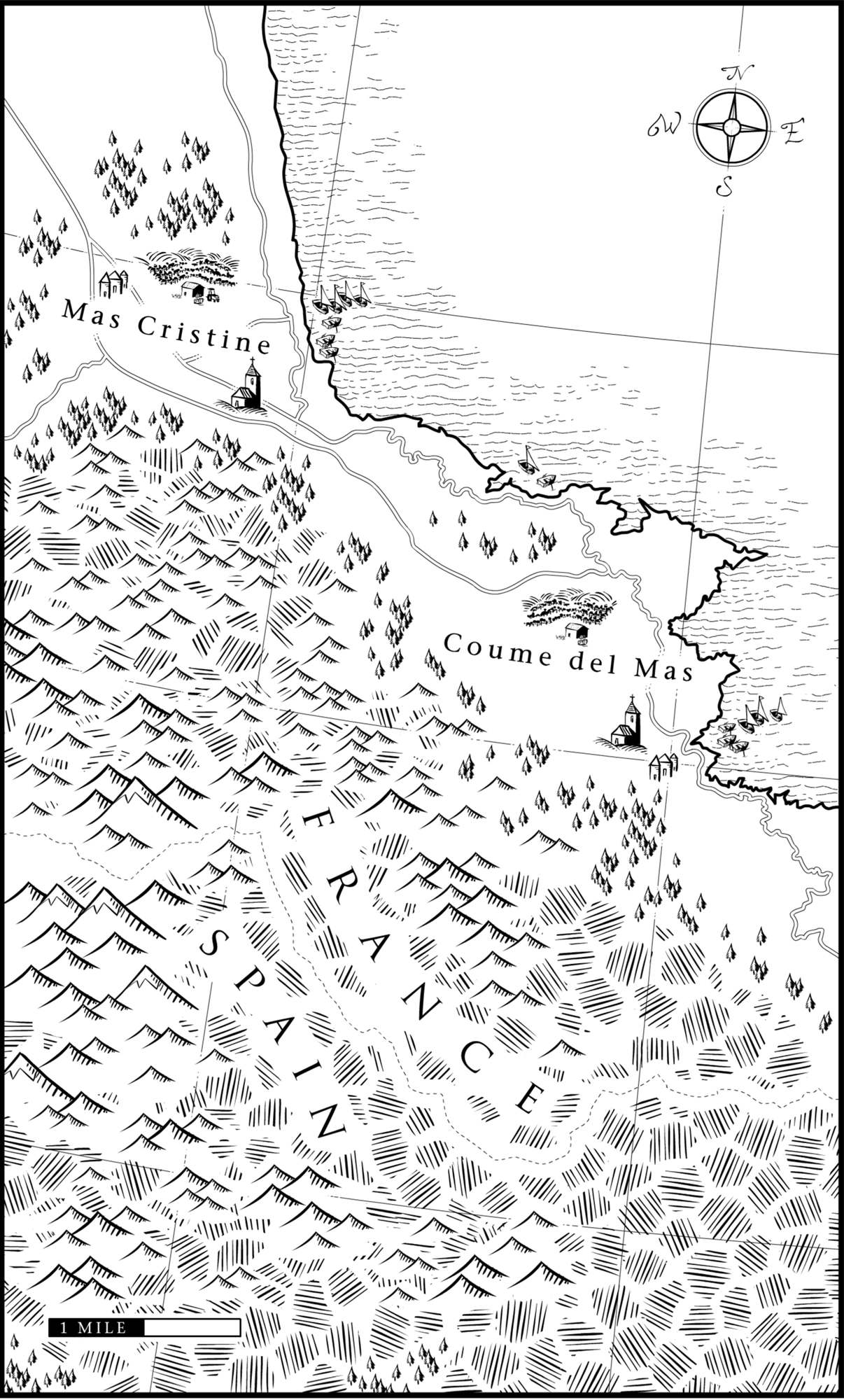

The south-eastern coast of the Roussillon

INTRODUCTION & EXPLANATION

Th is is the second book that came to me on a roundabout. The first one is another story, for another time.

This particular roundabout is the one that sits just off the first exit for Argels and Le Racou after you leave Collioure on the autoroute headed towards Perpignan. Its still in the hilly bit, before the flat bit. We were going the other way; towards Collioure, from Argels. Andy was driving. He features quite heavily in this book, as its him that I make wine with. We were heading back towards Collioure from the winery and as we were crossing the roundabout and curling off on the exit towards town, I mentioned that some day I wanted to write a book about wine and this place, that I wanted to call it Where the Mountains Meet the Sea . I was telling Andy because hed mentioned the phrase that I wanted to be the title a few vintages before and I felt that quietly mentioning it without him saying, Hey, thats my fucking line would be his tacit approval of the title. As we took the coast road into Collioure, up and down the hills covered in terraced vines, the sea on our left, and the taller foothills of the Pyrenees rising in front of us to the right, it seemed a good title. At that point thats all it was, just a title and a mention of intent.

Its not even that title anymore.

And some day turned out to be somewhat sooner than I expected.

This isnt a wine book, not really. It has quite a lot of wine in it, both made and drunk. It has some vinous vocabulary, and even a glossary to provide some manner of guide to words like remontage and residual sugar. But the intent is not to teach you everything about wine in the Roussillon, Collioure and Banyuls. Its not a reference guide; I dont even give the addresses of the wineries that I work at (you can probably find them online). Nor is it a collection of tasting notes or maps or diagrams. There are no photos of pristine grapes bathed in the Mediterranean sun. Instead there are stories; the stories about the place and the people that take wine from grape to bottle.

I should also point out that the experiences written here are mine. I dont know of any winery that does things exactly the same as any other winery. The comportes we use hold kilos worth of grapes, the comportes they use in Chablis hold kilos worth. Many wineries dont use comportes; everything just gets bunged into the back of a tractor. Nothing contained in these pages should be considered ubiquitous in the wine world, save perhaps the difficulty of the work and the devotion of those that do it.

While it is a book of stories, it is not without points of reference. Some are scientific, some are historical and some are geographical. I have asked for advice and clarification from several people, though all of the research Ive done is my own work. Andy Cook provided the vast bulk of technical knowledge and advice regarding winemaking, but any errors are mine, not his.

RWHB

June, 2013

MOUNTAINS & WINDOW SEATS

I used to go straight for an aisle seat. The aisle seat meant that, if I had to, I could get up and down without bothering anyone. A good flight was one where I sat down, buckled my seatbelt, pulled my hat over my eyes, fell asleep before take-off and woke to the bump of touch down at our destination. If my eyes did open, I might plug my headphones in and shift a little to get more comfortable; kick my shoes off and make fists with my toes. Im not chatty on planes, and want them to simply bring me from one place to another. Cocooning myself in sleep, music and maybe a book seemed the best way to do that. Sightseeing could wait until landing.

Perhaps a part of it is growing up. Rightly or wrongly, I viewed the window seat as a feature of an excited childhood. The image of huge tracts of the earth passing in what seems to be slow motion, and in miniature, fires the imagination. Tiny towns, patchwork farmland, mountainous clouds obscuring all of them; more than any other experience of youth, looking out the window of an airplane gives the most incredible glimpse of the wider world around you. Its your first introduction to the scale of the earth.

Somewhere along the way, I stopped caring about the scale of the earth. I wore my callousness to it like a badge of honour, and my cocoon on flights made me impervious to whatever might go on in the rest of the world.

In January 2008 , after a flight from London to Perpignan, I decided to start sitting in the window seat again. I felt the plane begin its descent, and as our path got steeper and steeper, I kept looking towards the window, over the two people sat next to me. Through the porthole on one side, I saw a plain, dotted with the odd inland sea, stretching out alongside a slate, angry Mediterranean. On the other stood snow-capped mountains, dark forests and the singular peak of what I would later discover was the Canigou, the , foot mountain sentry that stands guard over the Plaine du Roussillon.

Lone mountains strike a nerve. Whether its the peak of the Matterhorn, the Paramount Pictures logo or Tolkiens evocative description of Smaugs lair, we feel some sort of deep awe when presented with such natural monuments. Like looking out of an airplane window, they provide a sense of scale.