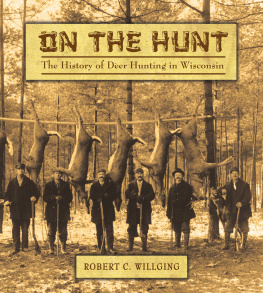

I have spent all of my fifty-six deer seasons hunting out of the same hunting camp and wouldnt have it any other way. Although Ive read numerous books and magazines about white-tailed deer hunting, Ive noted that very little is ever mentioned about the activities that go on in hunting camps after the hunt has concluded, and what compels generation after generation to revisit their beloved deer hunting camps each fall.

When the trees start changing colors in the autumn and the leaves begin to fall, I yearn to return to our deer camp. The closer we get to deer season, the more intense those feelings become. I long to smell the familiar aroma of gourmet comfort food cooking in the antique wood stove, and to dine on the time-tested meals that we have served year after year. I am anxious to spend long evenings in the warmth of the camp, sitting around a large table with the people I love, playing cards, exchanging stories, and enjoying the multitude of snacks and beverages that are always available. I look forward to getting away from things most people consider civilized and necessaryno television, no blaring radios, no telephones, and no computers.

You will find some interesting deer hunting stories contained herein, but this is not just another book about hunting white-tailed deer. What these stories demonstrate is that the deer hunt is actually only a small portion of what it means to gather together every fall. To all of us who hunt out of a deer camp or belong to a hunting group, deer hunting is much more than tramping through the woods to shoot a deer. It is about gathering with the same people year after year and strengthening the bonds that develop between fathers and sons, family members, friends, and other hunters with whom one has the privilege of sharing the woods. The memories, the stories that are told time and time again, the camaraderie, the laughter, and the time one is able to spend away from the normal routine of daily life, reacquainting oneself with the joys of natureI consider all of these things more important than the hunt itself.

In the mid-1950s, Sawyer County, along with many other counties in Wisconsin, began to issue Recreational Use Permits on a first-come, first-served basis to people who wanted to construct cabins on county forestland for the purpose of hunting.

These permits were allowed based on Wisconsin State Statute 28.11, which authorized Sawyer County and the other counties in the state to provide recreational opportunities to the public. The statute was vague and, as a result, Sawyer County began issuing permits for hunting cabins at a cost of ten dollars per year, while limiting the number of permits to one hundred.

A permit allowed the permittee to rent county forestland on which to place a hunting cabin. The guidelines for the size of the cabin were dictated by the county, and the cabin was not to be built on a permanent foundation. The permit was conditional and required that the permittee not cut any green timber, commit waste, or do any damage to the county forest lands. The only privilege given the permittee was to use the cabin for hunting purposes and to cut dead timber for the purpose of providing heat to the cabin. Although the permits were very restrictive, many hunters in the area found them to be ideal for establishing hunting camps in the forest at an affordable cost.

In Hayward, Wisconsin, in 1954, my dad and several of his friends had talked about starting a deer-hunting camp. At that time, memories of World War II were still fresh in peoples minds. The members of the Greatest Generation were optimistic, though many didnt have anything but their youth and the belief that prosperity could belong to anyone who worked hard in America. Thats what my father and his friends believed. My father, Marvin Hanson, married Violet Erickson, whom he met at the Smith Lake Pavilion while performing in the Jack Olson Orchestra in 1939. He entered the navy and returned to his hometown of Hayward after the war ended. At thirty-seven years old, he and my mother, along with my sister Marilynn and me, lived in a house on Fourth Street, which he built under the G.I. Bill.

Sometimes at my dads grocery store, sometimes on Saturday or Sunday evenings when families would get together and pass a dish for a potluck get-together, sometimes in the backyard, but most often while sitting around the kitchen table sipping on a beer, my dad, Merle Dunster, Kenneth Sugrue, Howard Nystrom, and Alvin Adder Madson would talk about their dream of building a hunting camp. That dream would become a reality in November 1955 and would become known as Blue Heaven, named after the popular song My Blue Heaven. Adder loved that song and suggested they call the camp by that name.

The group of men who dreamed it, built it, and hunted from it until the day they died called themselves the Jolly Boys. This book is a recounting, as best as memories and written testimony allow, of the traditions, camaraderie, and love of the hunt that developed in the rustic atmosphere of a Wisconsin deer camp. This is the story of the legacy of one of Haywards original hunting camps, which lives on, now more than half a century later.

I was ten years old in 1954, and life was a lot less complicated than it is today. My family didnt own a television set. We couldnt afford one, and those who could found very little to watch on their TVs because Hayward was too far from any metropolitan area to get reception. Very little was purchased on credit back then. Everyone tried to make ends meet with what they had. In Hayward, everyone knew everyone else. Nobody locked their doors at night or when they were away. Most families owned one vehicle, and most were old clunkers, no longer capable of long trips. Very few cars had radios, so when you did go somewhere, you made your own entertainment by singing, which seemed to make the trip shorter. Children spent lots of time outside and entertained themselves with games of make-believe war or cowboys and Indians. We were never bored and neither were our parents. The adults entertained themselves by getting together with friends, relatives, or neighbors. And people always sang at these get-togethers. Everyone worked at least six days a week. Some worked even more. My parents owned a grocery store that stayed open from 7 a.m. until 7 p.m., and sometimes later.