gardenlust

A BOTANICAL TOUR of the

WORLDS BEST NEW GARDENS

CHRISTOPHER WOODS

TIMBER PRESS

PORTLAND, OREGON

For Mary.

I could not have done this without you.

And for the gardeners of the world.

You with the crazy eyes and rough hands.

You who are so much in love with growing things.

You artists and scientists, poets and painters, protectors and advocates.

You who fall in love again and again.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I FELL IN LOVE WITH PLANTS when I was very young. Every autumn, my father and I would travel from our home in London to a small village in Northamptonshire. We would walk for miles, he picking mushrooms in the morning and blackberries in the afternoon, and I eating them. Britain had not yet fully recovered from the Second World War. Farms were small and wheat fields were full of poppies. Thousand-year-old hedgerows contained a garden of hawthorns and dog roses, and skylarks sang so high in the sky they were all but invisible.

Much later, like so many of my generation, I considered moving away from the city to live an idealized life in the country. I took a small step first and became a gardener at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. I planned on working there for just a few months, but on the first day, I was hooked. It takes hold quickly, this plant addiction.

I then went on to work in a succession of gardens: Portmeirion in Wales, where I discovered the wonders of Himalayan rhododendrons; Batemans in Sussex, and Cliveden in Berkshire, where I learned about the history of gardens and the bureaucracy of management. All the while, I was falling deeper and deeper in love with growing things.

I am a restless man at heart, though, so eventually, feeling confined by Britain, I moved to the United States. A whole new world of plants and gardens was mine to explore. There was even sunshine. I spent twenty years working in a garden in the suburbs of Philadelphia, Chanticleer, before finally giving in to my desire to have a long-term affair with California. I initially moved to a two-room shack on the edge of Los Padres National Forest. My Zen credibility was high. I learned many things in the West, from how to remove rattlesnakes from my kitchen to which California lilac turned the mountains from white to pale blue, then to deep blue and back to white again. I never learned to surf.

At this point in my life, I have more or less replaced constant resettlement with near-constant travel. I continue to fall in love with this extraordinary world and its botanical marvels. Blue poppies in the Himalayas. Aloes in the desert. Banksia in the Blue Mountains of Australia. Orchids in Laos. I am a romantic fool. Its a curse and a blessing. It probably makes me look at things from a somewhat nave perspective, but the perspective is mine.

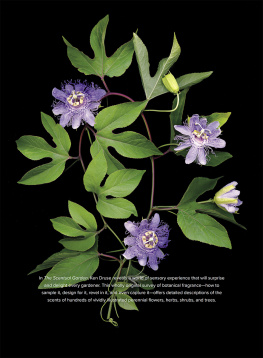

I want everyone else to fall in love with our world too, and with gardenings potential for adding beauty to the world. Hence this book. After a life spent in public horticulture, I began traveling the world in search of gardens that intrigued me by offering a particularly modern take on using inherently interesting plants, fresh approaches to how to place them that result in the creation of something new or at least unconstrained by the weight of tradition, and faraway places where I could touch, feel, and breathe in mass gatherings of the plants I had too often only experienced as lonely specimens in the old-fashioned and ecologically clinical settings favored by too many Western botanical gardens. I moved from conformity to chaos, only to find out it wasnt chaotic at all.

I set myself a criterion of visiting only gardens created in the past two decadesI was in search of true twenty-first century gardens. So in short, this is a book about contemporary gardens and landscapes, but with every word, it is a love letter to the planet and to the people who have dared to create beauty, who have devoted their lives to helping others learn to see that beauty.

This book therefore naturally projects a quite personal opinion of what constitutes good innovation in garden design. I ask the reader to trust that my qualifications permit me to share my opinions. Brazen modifications of iconic historic gardens, such as Alnwick in the U.K., are always good. Imagining an entire forest smack in the middle of a crowded Tokyo business district, also good. Turning the bark of scribbly gum trees into inspiration for fanciful pathways, such as at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Cranbourne, in Australiagreat. Gardens that envelop you in moody botanical opulence, such as the gardens of Juan Grimm in South Americafantastic.

Fifty designers work is presented here. Many fine gardens are undoubtedly not included. Even I, with my enthusiasm for travel, am aware of my limits. I have chosen from among botanical gardens, public parks, private residential gardens, and corporate landscapes to illustrate the diverse range of thinking and expression that permeates contemporary design. I have asked myself what forms gardens can take now, what needs they must fulfill, and what the indicators are of how garden design will progress as the century advances. Each selection answers one or more of these questions in a significant way. Many new and important gardens have been created in the past eighteen years, but which successfully illustrate possibility?

Our view, our interest, and our understanding of what gardens and landscapes can accomplish have changed radically in the past few years. What makes modern landscape design different from most other forms of contemporary art is our growing understanding of the effects of deforestation and climate change, the lessons to be learned by studying ethnobotany, the importance of an urban forest, and the impulse to use what we hope are ecologically appropriate or native plants. Several themes run through the stories that follow, threads that make an interwoven pattern. No garden touches on just onemost have all of them.

BEAUTY The desire for beauty, often expressed as a deep need to embrace nature in our daily lives, has become more important than ever. Its technology backlash.

We continue to visit the grand palace gardens of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries but the modern palaces are now global corporate and government centers. A question rarely asked is how beautiful should they be?

The country garden has become a postmodern collection of clean lines and smooth surfaces, geometric shapes and repeating patterns, in an attempt to create a garden that has a controlled and organized appearance. Conversely, it has become a tiny prairie, a meadow, a memory of wildness and a metaphysical murmur.

Often, people grow quiet when they enter a garden. In the face of so much beauty, there is often not much to say. In the Garden of Five Senses in India, even the young lovers are quiet, and the meditators, sitting in the shade of a tree, come to a place of beauty to sit in peace.

In the Naples Botanical Garden in Florida, visitors write down the name of plants and marvel at the color of bromeliads. They go out on a boardwalk overlooking the wetlands and their posture changes, backs straighten, mouths open, as they absorb the sun on the grasses and the flash of a heron taking flight.

In a small residential garden in the Netherlands, a mother says, This is my house, this is my garden, this is my life. I want it all to be beautiful.