THE STORY OF

KEW GARDENS

IN PHOTOGRAPHS

LYNN PARKER AND KIRI ROS-JONES

Acknowledgements

We have drawn on the knowledge and experience of many of our Kew colleagues and would like to thank all of these for their assistance and support. In particular we would like to thank the following for helping locate images: Barbara Lowry, Trishya Long, Stephanie Rolt, Emma Latham, Elisabeth Thurlow and Marie Humphries. To our colleagues Julia Buckley, Marilyn Ward, Lorna Cahill and our other Library, Art and Archives colleagues, who along with the above mentioned have been kept extremely busy whilst we have been working on this book! To Fiona Ainsworth, Jonathan Farley and all our other colleagues who have helped with the proof reading. To Stewart Henchie, Nigel Hepper, Martin Staniforth and Mark Nesbitt for letting us pick their brains and sometimes their photographic collections.

A special thank you to Paul Little for dealing with the deluge of photographic requests and to Andrew McRobb. To Hina Joshi for her help with the cover design. To Gina Fullerlove and Tessa Rose and their teams for their input and expertise and turning the idea into a reality. And a big thank you to Christopher Mills, for providing the idea behind the book, reading our many edits, keeping a calm head and enabling us to have the time to work on such an interesting project. And finally we would like to thank Andrew Davis and Raymond and Dominic Weekes.

This edition published in 2013 by Arcturus Publishing Limited 26/27 Bickels Yard, 151153 Bermondsey Street, London SE1 3HA

Copyright 2013 Arcturus Publishing Limited

Text and images The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person or persons who do any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

ISBN: 978-1-78212-748-2

Contents

Introduction

T his book is not a comprehensive history of Kew, but rather seeks to reveal stories of a much-loved garden through its photographic collections. For some it will evoke fond memories of a place well known, while for others it will provide the chance to encounter Kew for the first time.

The blossoming of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, into a public institution in 1841 coincided with the arrival of photography, and through this book we witness the development of both. Photography was introduced to the public in the first half of the 19th century, born out of the experimentations of inventors such as William Henry Fox Talbot in England and Louis-Jacques-Mand Daguerre in France. While this new, constantly evolving technology was to become the ideal tool to chronicle a rapidly changing era, Fox Talbot initially used it to explore his passion for botany, disclosing that the first subjects of his photogenic drawings were flowers and leaves.

There are many stories to be told, charting Kews evolution into a major public institution through its landscape and architecture, but also through its staff and visitors. Many of these photographs have never before been published, and through this book we are pleased to share them with a wider audience. The photographs document periods of expansion, prosperity and adversity and place Kew in an international context through its colonial links and response to global conflict and the aftermath.

Kews substantial photographic collections have been gathered from a number of different sources, from commercial postcards to expedition albums, spread across the Archive and Art collections. Kews first official photographer, Gerald Atkinson, joined Kew in 1922; before this time, self-employed photographers were commissioned to capture the gardens for a range of purposes, producing postcards and illustrations for publications such as The Journal of the Kew Guild. The largest influx of images came in 1928, when Kew purchased 5000 negatives from the photographer Edward Wallis, and this now forms the core of the historic collections. During the 1960s, the Gardens established a photographic unit, which still contributes new material to the collections.

In the days preceding photography, naturalists would sketch the plants that they botanised, the landscapes they witnessed and the different cultures they encountered. As the new medium of photography emerged during the 19th century, so botanists gained access to a fresh way of documenting their experiences. In the early years of photography, equipment was heavy and cumbersome; glass negatives were easily damaged and vulnerable to light exposure and insect attack, and the cameras themselves were susceptible to moisture damage. Later, even as equipment became more portable and easier to use, many of the same difficulties remained. Yet while drawing continued to be an important tool in the plant-hunters oeuvre, and is still the preferred medium with which to record specimens, the photographs that were brought back provide us with a valuable insight into what life was like in the field.

Photographic collections have also been a valuable teaching tool at Kew in the Museums of Economic Botany and, later, in the School of Horticulture, both of which have amassed large and varied picture libraries. The latters slide library includes images of horticultural practice as well as student life, while the Museums collections are a mixture of images of colonial botanic gardens, photographs by private individuals and records of economic crops and plantations taken by government employees, as well as promotional material provided by industry.

This book contains a selection made from the thousands of images held at Kew, intended to give an insight into its history in the 19th and 20th centuries. These photographs document the substantial changes and momentous events which influenced its progress as it grew from a small, private, royal botanic garden to the internationally important scientific centre and leading visitor attraction that we know today.

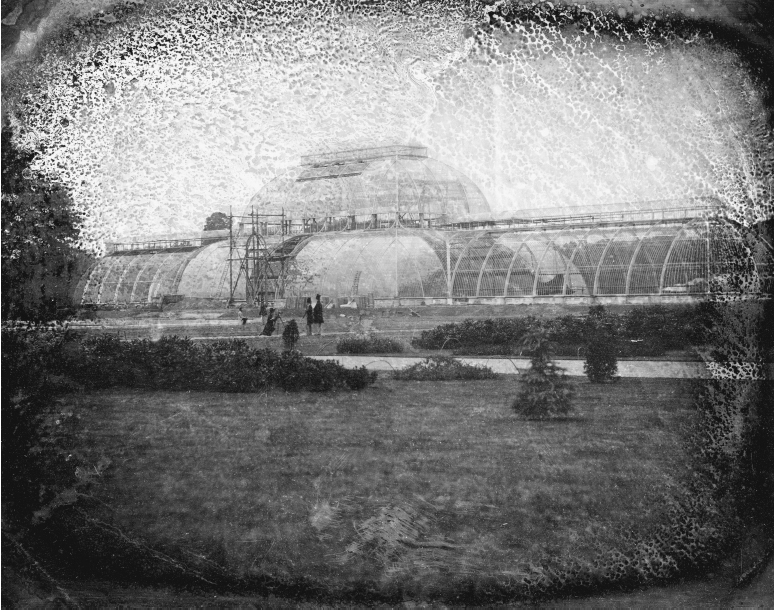

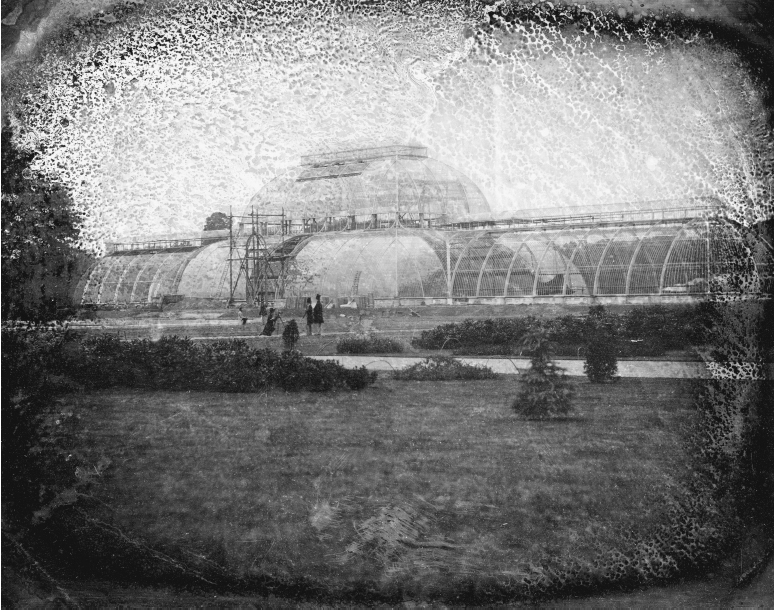

The earliest image of the exterior of the Palm House was made using the daguerreotype process, which was perfected in 1839 and remained popular until the 1850s. Images were produced on a copper sheet, thinly plated with highly polished silver, and their size, determined by the cameras used to produce them, was relatively small. Extremely fragile and particularly sensitive to being handled, the surface is mirror-like and has to be viewed at an angle. As well as being susceptible to abrasion, it is also vulnerable to tarnishing.

Constructing Kew

Kew Gardens, now a World Heritage Site and one of the most famous botanic institutions in the world, developed from a large stripfarmed field belonging to a private estate. It was neighbouring Richmonds royal connections that brought prosperity to the area from the 16th century onwards, with courtiers who wished to live in proximity to the newly constructed Richmond Palace, building resplendent homes such as the Dutch House (later Kew Palace) on land leased from the Kew estate.

Next page