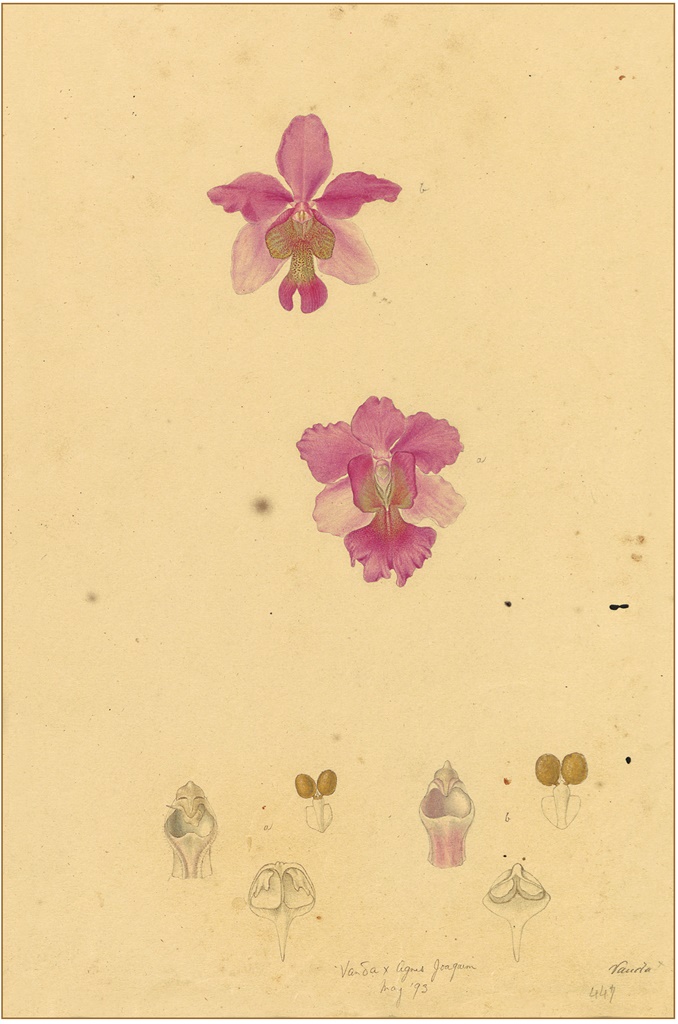

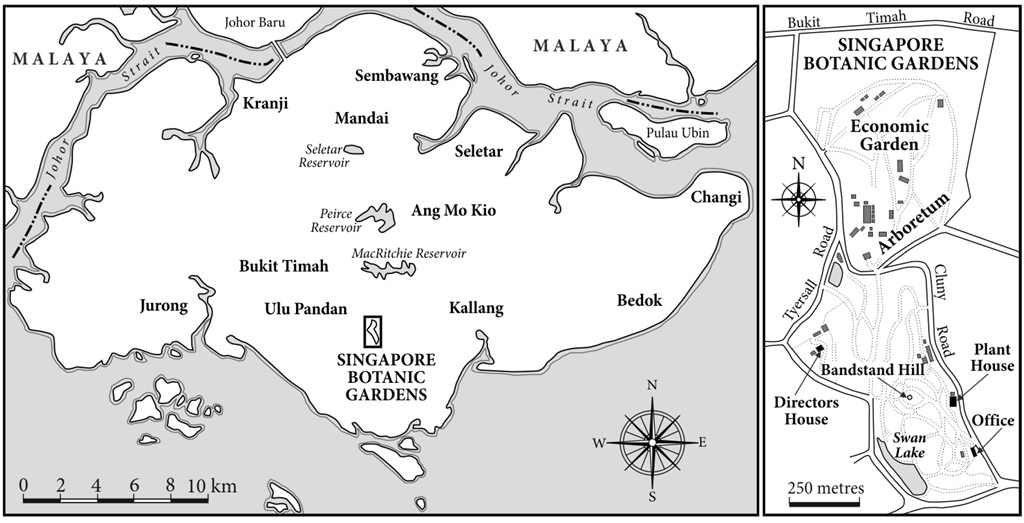

Illustration of Vanda Miss Joaquim. The work is unsigned, but is dated from 1893. Image courtesy of the Library and Archives of the Singapore Botanic Gardens.

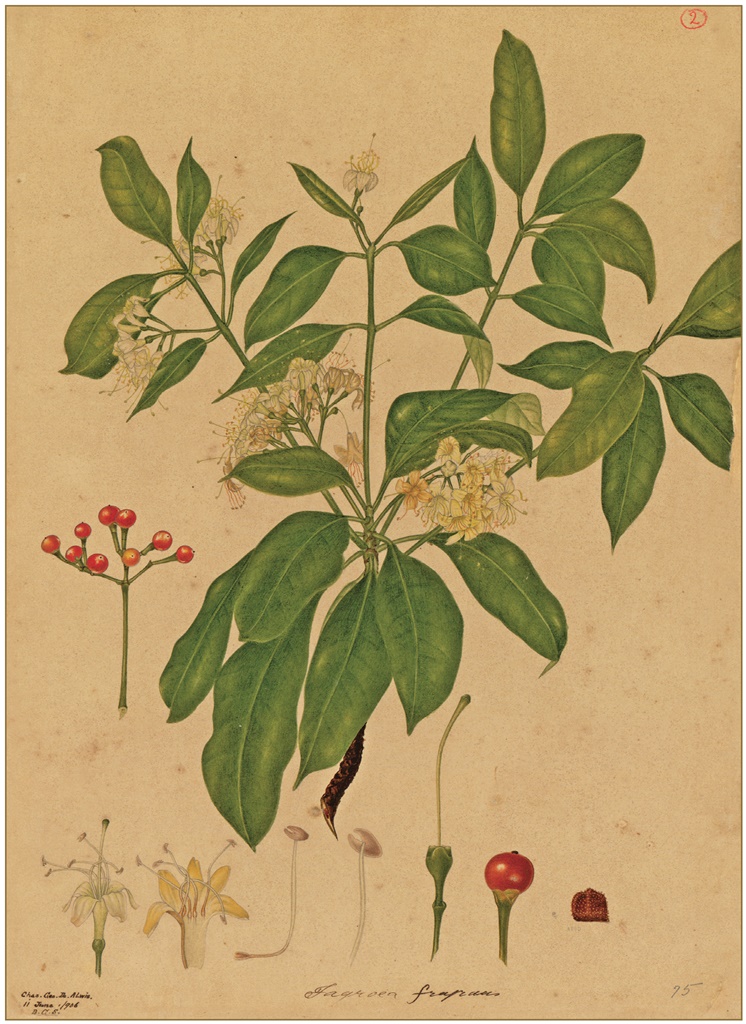

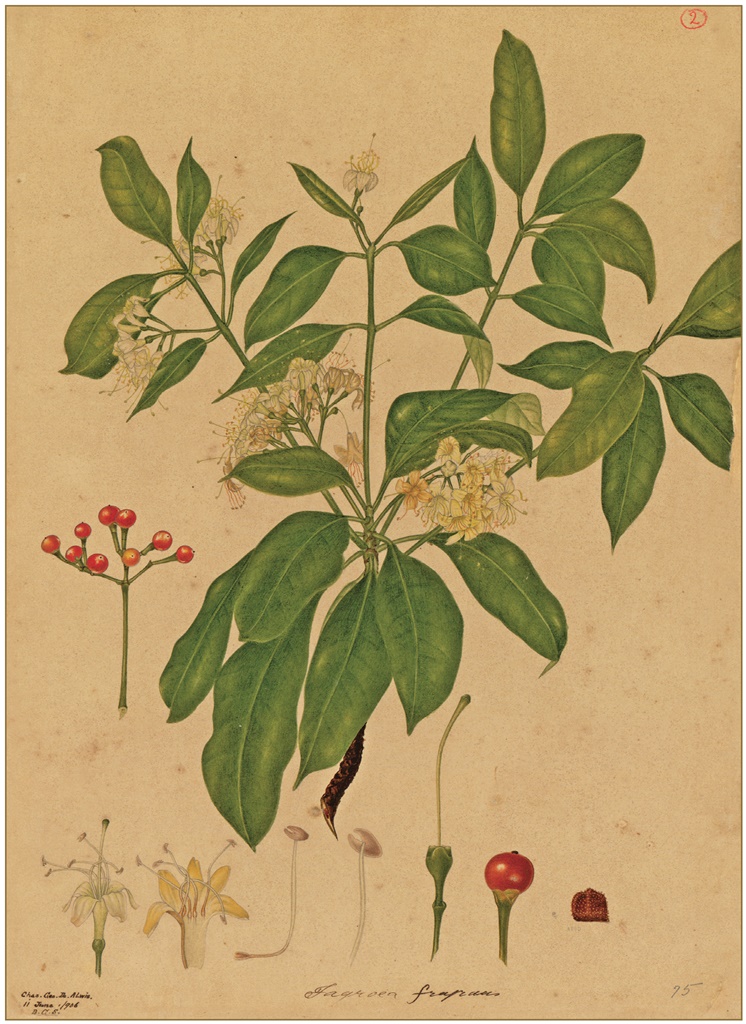

Botanical illustration of Cyrtophyllum fragans, better known as the Tembusu tree, by Charles De Alwis. As early as 1888 H.N. Ridley argued that this species held great potential for forest conservation programs in Singapore. Image courtesy of the Library and Archives of the Singapore Botanic Gardens.

Acknowledgements

A single-authored monograph is never written alone. It requires the help and support of a countless number of people, and this is true with this work. Over the past few years I have incurred numerous personal debts of gratitude to numerous individuals and institutions.

The assistance of staff members from various libraries and archives has allowed me to collect materials, and without their help this work would not have been possible. The most influential was Christina Soh at the Singapore Botanic Gardens Library and Archives. Christina and her staff, particularly Zakiah binte Agil, have always been there to provide help and suggestions as I bothered them to help find another annual report or a botanical illustration. Their assistance has been invaluable. This also extends to many others at libraries, archives and herbaria scattered around the world. Among those who went beyond the call of duty were David Middleton and Siti Nur Bazilah Mohamed Ibrahim from the Herbarium at the Singapore Botanic Gardens, as well as Miriam Hopkinson and Lorna Cahill at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew Library, Annabel Teh Gallop at the British Library, Rohayati Paseng of the University of Hawaii Library, Michael Palmer at the Zoological Society of London and Tim Yap Fuan from the Library at the National University of Singapore.

Numerous individuals have also assisted me by providing moral support and engaging in discussions that greatly contributed to my knowledge and understanding of the history and culture of the Singapore Botanic Gardens and its role in regional and imperial societies. In hallways, libraries and classrooms, friends and colleagues such as Brett Bennett, Brian Farrell, Ian Gordon, Andrew Goss, Ho Chi Tim, Sandra Manickam, Tony ODempsey, Sandeep Ray, Fiona Tan, John van Wyhe, Yong Mun Cheong and Alan Ziegler allowed me to think through my arguments and then defend them while providing their own insight into local history, science and culture. In addition, students at the National University of Singapore, particularly Eugenia Chin Jiamin, Jonathan Lau, Loh Pei Ying, Christabelle Ong, Poh Yu Hui, Suen Jiamin and Wong Yeang Cherng, introduced me to a variety of unexplored topics in the history of the Singapore Botanic Gardens through their own research interests. In Europe and the United States Ryan Bishop, Cynthia Chou, Will Derks, David Lihani and Jan van der Putten provided moral support and place of respite where I could think through my ideas. Philip Barnard, Cheryl Lester, Julia Barnard, Jordan Wade and particularly Maureen Danker provided the support only family can. Finally, Martin Bazylewich, Michael Daly, Patrick Daly, Mark Emmanuel, Bertrand Grandgeorge, Jon Hammond, Alvin Hew, Li Hongyan, Mok Mei Feng, Joanna Tan, David Teague, Ted Wong and Chris Yong were good friends during this process and have made living in Singapore enjoyable. Their prodding and advice played a much larger part in the process of developing this book than they can imagine.

There were also a handful of individuals who made an extra effort and greatly influenced this work. Primary among them is Nigel Taylor. As the Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens he has been an ambassador of science and heritage in his efforts to instill a curiosity about its wonders. His continual support for this project has allowed it to proceed as quickly as it has, and it would have been impossible without his presence at every stage of its development. I also would like to thank John Elliott and Tan Wee Kiat for the insight they provided into the role that orchids and the modern nation-state have played in the history of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, as well as Lawrence Wood and Christopher Yong for helping me with images that appear in this book.

Finally, special attention should be given to those closest to me. My parents, Harry and Wanda Barnard, have provided moral support throughout my life and have been living examples of curiosity and the desire to learn more, while my wife, Claudia Ting, has provided love and encouragement throughout this project. This book is dedicated to them, as Claudia always enjoys a walk in a garden while Harry and Wanda always enjoy reading about one.

CHAPTER ONE

Natures Colony

Gardens are artificial. They are self-contained entities in which flora and fauna are cultivated, controlled and manipulated to serve the interests of the gardener. They reflect attempts to influence nature, ultimately to shape it, and are created to serve those with power over their grounds. Inside these gardens the interests of the gardeners are multifaceted. A garden can be for recreation, where the visitor strolls, exercises or relaxes while escaping the daily stresses of life. On another level a garden can function as an educational center, where plants are grown, animals kept and ecosystems conserved while visitors learn more about the natural world. The efforts to maintain the flora and fauna of these gardens can also be transferred to larger society to create a more pleasant environment throughout a city, state or region. Finally, a garden can function as a center for research that is vital to the development of scientific knowledge, which often influences the economics, politics and cultural matrix of states and societies. Gardens on all of these levels are artificial, in that they are created and reflect the needs and desires of the society and people that cultivate them.

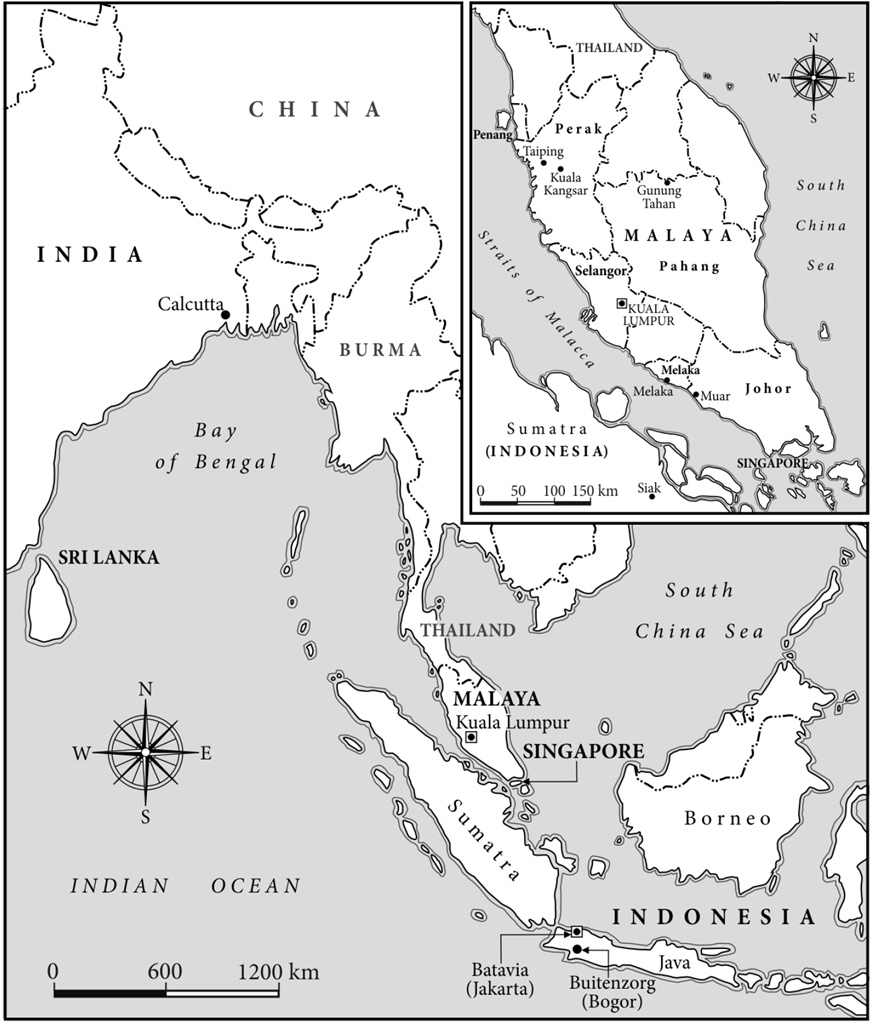

This is the history of one such garden, located on an island in Southeast Asia. Since the mid-19th century, the Singapore Botanic Gardens has operated as a recreational park while also having a far broader impact beyond the boundaries of its grounds in environmental, political and social terms. Fundamentally, the Singapore Botanic Gardens created knowledge and became a site from which its gardeners spread their influence into numerous realms through a mastery of nature, resulting in expanded imperial control over the region and later the functioning of a small, independent nation-state.

The modern botanical garden arose alongside such power gardens. These new institutions were initially associated with medical faculties, as the study of plants was vital to the development of pharmacology and the education of physicians during the period. Located in cities such as Padua, Leiden and Gothenburg, these gardens quickly transformed into playing a role in understanding the flora discovered in the New World and Asia as Europeans moved outward in exploration. A botanic garden thus became a fundamental component in the development of early modern societies and trade empires as commerce focused around a foundation of knowledge of the natural world, particularly plantsranging from pepper to cloves and nutmegthat were key trade products of the pre-industrial global economy. This made botany one of the most important instruments of colonial expansion. An understanding of plants was the basis for power, and the transformation of this knowledge into a control over land and economies in distant colonies occurred in botanic gardens.