A WORLD OF GARDENS

For EMILY

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2012

Copyright John Dixon Hunt 2012

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by Toppan Printing Co. Ltd.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Hunt, John Dixon.

A world of gardens.

1. Gardens History.

2. Gardens Design History.

3. Gardens Styles.

4. Gardens Social aspects.

I. Title

712.09-dc22

eISBN: 9781780233789

A World of Gardens

John Dixon Hunt

REAKTION BOOKS

Contents

Introduction:

The Garden World and the World of Gardens

Gardening, after all, is one index of the history of men.

GEOFFREY GRIGSON

G ardens of all sorts come in all sizes and guises. And our interest in them also takes many approaches. We study the process of their design, their built forms, their materials and plantings, their meanings, their use or how they are experienced on the ground and represented in word and image, their decay and maybe their recuperation. We are interested in who their designers were, who commissioned them, and the motives of both designers and patrons, along with the political and social contexts in which gardens came into being. But sometimes we also construct our own memories of these places.

A history of gardens is best undertaken as a cultural history, even if its primary focus is design, botany, hydraulics or sculpture. People engage in place-making because our choice of habitation is of supreme importance, as we find our identity and a sense of belonging in the process of colonizing and cultivation, which the word culture (derived from Latin colere) implies. It is not enough to look at gardens for their style (endlessly and emptily touted as formal or informal, baroque, picturesque, arts and crafts), nor even enough to assess their visual appearance. We need to ask why they came into being, what advantages and pleasures (including the visual, to be sure) accrue from them, and how and why they have survived, changed or vanished.

The range of places that can be envisaged within the category of garden is also enormous and various, and it changes from locality to locality, and from age to age. Yet this diversity does not wholly inhibit us from knowing what it is that we want to discuss when we think of gardens. Above all, it is useful to think of the garden as typically a place of paradox, being the work of men and women yet created from elements of nature, the two held in some precious and often precarious tension. And while a garden is often acknowledged to be a total environment, a place that may be physically separated from other zones, it also answers and displays connections with larger environments and concerns, not least agriculture and cities. Gardens, in short, are both entities within themselves and a focus of human speculations, propositions and negotiations, concerning what it is to live in the world.

Therefore this book will not be a conventional history, following the garden from its earliest to the latest manifestation in a series of waves, each gathering strength, then cresting and falling backwards, sometimes passing their energies from one to another; nor will it attempt to allude to every significant designer or every known garden. It seemed less interesting to chronicle design innovations, which are always premised on the elaboration or even rejection of previous models; but as Joseph Brodsky noted about Ezra Pounds famous declaration Make It New, the true reason for making it new was that it was fairly old. Rather, this book focuses upon mens and womens continuing responses to rural and urban forms and their re-workings of both the natural world and the spaces of human habitation. Even a modest survey of gardens from China to Peru will notice the recurrence of types and uses of gardens in many different times and places: sacred landscapes, landscapes of play and amusement, scientific gardens, gardens for urban life, gardens for private seclusion and meditation, prosaic and practical sites, poetical and symbolic places, creations that celebrate locality or establish nationhood. Certainly cultural assumptions and local geography have always shaped such sites and their meanings, and those particular forms and local associations will be explored. Yet equally instructive is the fashion in which gardens are hospitable to a cluster of archetypal human needs and behaviour. So, while the structure of this sequence of essays does move chronologically from early examples to the most recent (and even future) ones, it also chooses to explore a more lasting, because synchronic, aspect of many types and sites. Since narrative process per se is not its ambition, an agenda of alternative issues will be canvassed: the recurrence of garden themes, topoi or commonplaces; the cross-cultural reception and exchange of forms and usage; the planning and development of gardens created for generic human activities; and the fashion in which gardens have shaped as well as given expression to basic human conditions and concerns.

While the chapters are offered largely in chronological order, readers may readily explore them in a different order, which is why occasionally quotations or sites recur in different discussions.

Each essay aims to be of similar length, despite the temptation to vary them: a kind of Procrustean measure has been applied, as it has been to the illustrations. These are also limited in number, though the images have been made as varied as possible in order to provide the fullest range of perspectives on garden art a mixture of plans, engravings, contemporary imagery and modern photographs. There will be a minimum of notes (or references), but there must be opportunities to suggest further readings as well as my own need to record debts to many other garden writings; since the study of gardens has exponentially increased in the last decade, readers must be made aware of these recent resources as well as of established authorities.

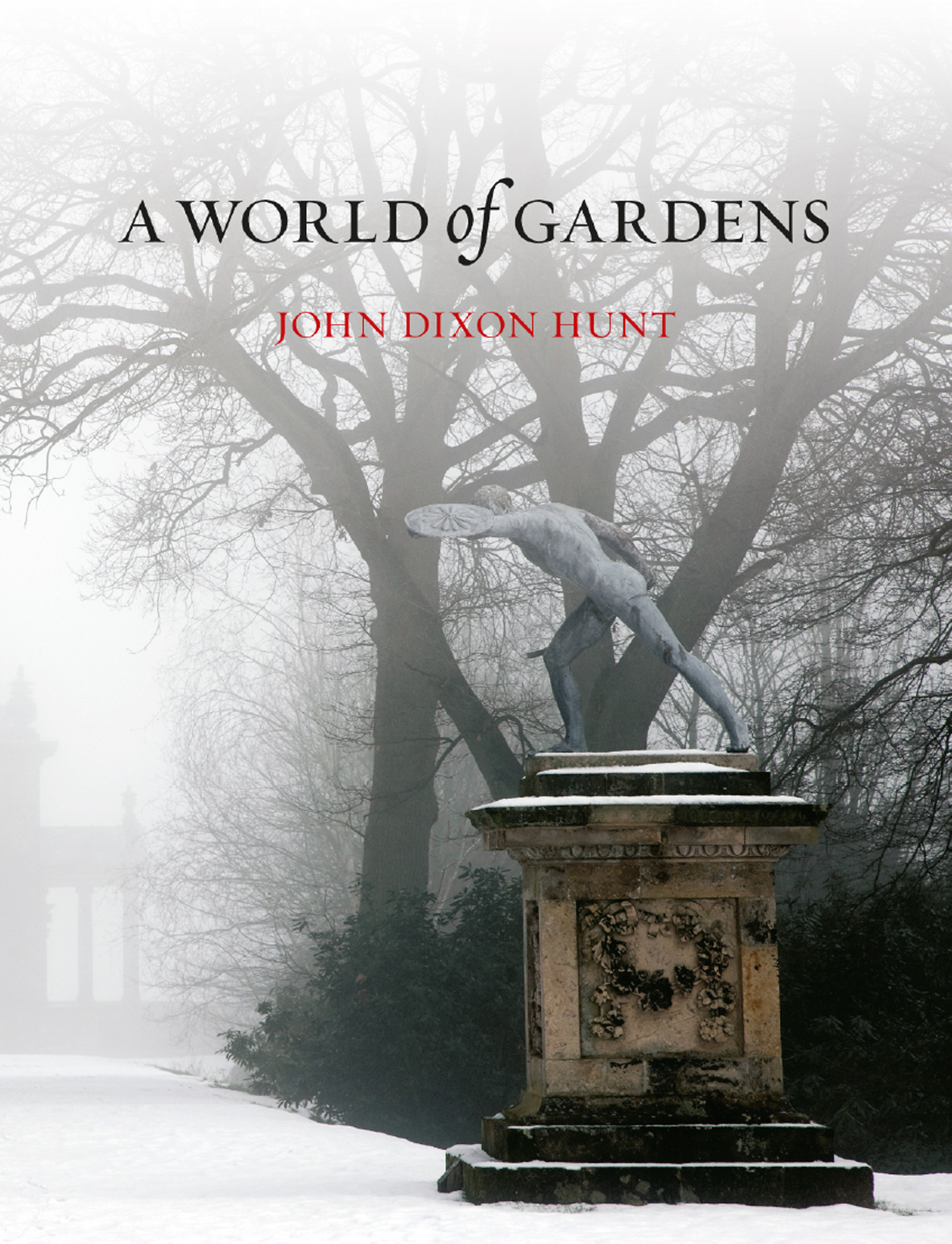

1 The fighting giants in the Parco di Mostro at Bomarzo, near Viterbo, Italy.

Sacred Landscapes from Delphi to Yosemite

T hroughout the world of gardens there are occasions when something particularly special about a place focuses and shapes both its design and its reception. This may be what was once called the sacred, as many early cultures declared. But in a modern world, grown secular and global, this often seems an inappropriate term. Nonetheless, there are places both old and new that call out for some recognition of this special site and its meanings. It may be that a particular place is mysterious, uncanny, even unsettling, because it is somehow removed from the ordinary world from which one has entered. We might think of Bomarzo, the wooded valley near Viterbo, where the items carved in the living rock giants, mythical beings, strange inscriptional injunctions, leaning houses still give one a strange feeling of disquieting puzzlement (