The University of Illinois Press

is a founding member of the

Association of American University Presses.

________________________________

University of Illinois Press

1325 South Oak Street

Champaign, IL 61820-6903

www.press.uillinois.edu

MUSIC IN AMERICAN LIFE

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

CHAPTER 1

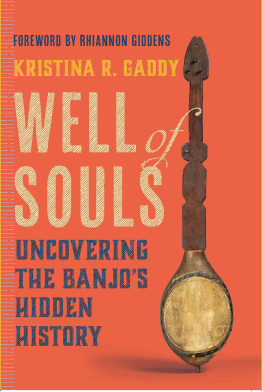

Banjo Roots Research

Changing Perspectives on the Banjo's African American Origins and West African Heritage

Shlomo Pestcoe and Greg C. Adams

Editor's Headnote

This chapter began as a response to the historic challenge issued by the late Dena J. Epstein in her 1975 article The Folk Banjo: A Documentary History to systematically investigate the historical record for period documentation tracing the banjo's roots, origins, and early history. Shlomo Pestcoe and Greg C. Adams have combined Epstein's research techniques with those of ethno-organology (the scientific study of music instruments and their musical-cultural contexts) to create an innovative scholarly approach, which they term banjo roots research. Here Pestcoe and Adams explain how this approach works, and share some of the crucial findings of this research that broaden the narrative of the banjo's history. They outline issues that will be dealt with in greater depth in following chapters covering the early history of the instrument, from its roots in West Africa to its origins in the Caribbean and its early history as an African American folk instrument, and then move on to the development of the modern banjo family and the current globalization of the banjo as a popular instrument in vernacular music forms the world over.

Banjo roots research is the empirical study of the banjo's early history, its origins in the early African diaspora in the Americas, and its deep roots in West Africa, the wellspring of the banjo's African heritage. Our work in this area of banjo studies is based on the trailblazing efforts of Dena J. Epstein (19162013), the mother of early banjo scholarship.

The principal focus of our approach to banjo roots research is the original African American gourd-bodied genus of the banjothe early gourd banjo, our general term for what Epstein called the folk banjo. It was the immediate forebear of the wood-rimmed five-string banjo (see This connection makes the early gourd banjo the ancestor of the modern banjo family we know today.

The scholarly infrastructure of our work is founded on two platforms: Epstein's application of library science principles to historical research; and ethno-organology, the study of music instruments and their musical and cultural contexts. Ethno-organology combines ethnomusicology's key principles, the study of music within any cultural context (or, as Jeff Todd Titon calls it, the study of people making music), with organology, the study of the historical development, classification, technology, and use of instruments. The synthesis of these two distinct research approaches facilitates multifaceted investigations of the historical record, combined with explorations of living traditions.

In this context, ethno-organological precepts and methodologies provide support for cross-cultural analysis and field research, on the one hand, and modern organological classification of music instruments, on the other. This approach enables us to identify and trace what we call the banjo genomethat is, the sum total of the various design concepts, morphological characteristics, and musicological factors that have defined the banjo family over the course of its historic continuum, stretching back to its African ancestors. At the same time, it also allows us to better study the traditions of the people who created and played these instruments, as well as the historic conditions and sociocultural matrices in which the banjo family, its ancestors, and its extant relatives first emerged.

First Banjos: The Early Gourd Banjo

The historical evidence shows that the banjo first appeared in the seventeenth-century circum-Caribbean, emerging from the harsh crucible of slavery and the transatlantic slave trade. The first banjos were plucked spike lutes, that is, plucked lutes on which the neck goes through or over the wall of the instrument's body. Akin to several traditions of plucked spike lutes still found throughout West Africa, they typically had a drum-like body, made of gourd (Lagenaria siceraria, also referred to as Cucurbita lagenaria L., which grows on vines)or, in certain cases, calabash (Crescentia cujete, which grows on trees)topped with a taut animal hide soundtable; a fretless full-spike neck that extended the full length of the body to pass through its tail end; and a floating (moveable) bridge that sat on the instrument's animal hide soundtable (see figures for these contrasting features).

Recognizing these distinctions, it is clear that the early gourd banjo was unique to the African diaspora in the New World. As such, it was the product of creolization (also referred to as interculturation), the same self-determined, internalized process that combined diverse African and European influences and admixtures in a syncretic fusion to create all other forms of early African American culture throughout the Americas.

Toward Greater Clarity

In the past, the banjo and its African forebears and kin were only considered in vague generalized terms as string instruments, without any real sense as to what kind of string instruments they were or where they fit in the greater music instrumentariumthe vast spectrum of all instruments of every description the world over throughout history. This inability to characterize the banjo and its relatives more precisely severely hampered serious analysis and study of these instruments. In order to surmount this obstacle, we use the organological analytical criteria and terminology provided by the system of instrument classification developed by the pioneering musicologists-organologists Erich Moritz von Hornbostel (18771935) and Curt Sachs (18811959) in 1914. Today the Hornbostel-Sachs (HS) classification system is the standard in the fields of musicology, ethnomusicology, organology, anthropology, museology (museum studies), and other scholarly disciplines.

According to HS categorization, the banjo and related instruments are lutes, that is, chordophones (string instruments) with a distinct neck and body. On most types of lute, various notes are made both by playing open strings and by stopping some or all of the strings at different places along the neck. Lutes are divided into two major categories based on how their strings are sounded: plucked lutes, which are played by plucking and strumming the strings with the fingers and/or plectrums; or bowed lutes (fiddles), which are played by drawing a bow across the strings. The banjo and its kin are, therefore, plucked lutes.

Using the HS classification we can further determine that the early gourd banjo, like its West African forebears and present-day kin as well as its North African cousins, was a spike lutea lute that has its handle (neck) pass through its

We can achieve greater specificity and accuracy in our classification of plucked spike lutes by subdividing them into two main categories based on the span of their necks in relationship to their bodies: full-spike, where the neck extends the full length of the body to pass over or through the body's tail end (see ). Recognizing that the early gourd banjo was a full-spike lute helps us to better refine and sharpen our comparative analyses of the vast family of West African plucked spike lutes and any potential relationships with the early gourd banjo.

At this point, we should clarify that another key element of our approach is to increase knowledge of the many plucked spike lutes still found throughout West Africa today. This aspect of banjo roots research first emerged in 2000, when the independent researchers Daniel Laemouahuma Jatta of The Gambia and Ulf Jgfors of Sweden introduced the banjo community to two traditional West African plucked spike lutes that were largely unknown outside the Senegambian region. They are the

Next page