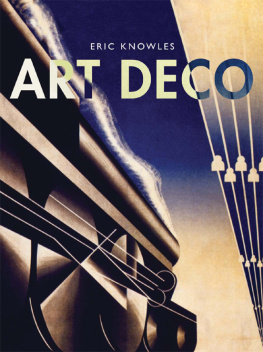

ART DECO

Green patinated art-metal figure by Fayral, of a young woman in a loose tunic dress holding a large hoop; c. 1930. Height 45.5 cm.

CONTENTS

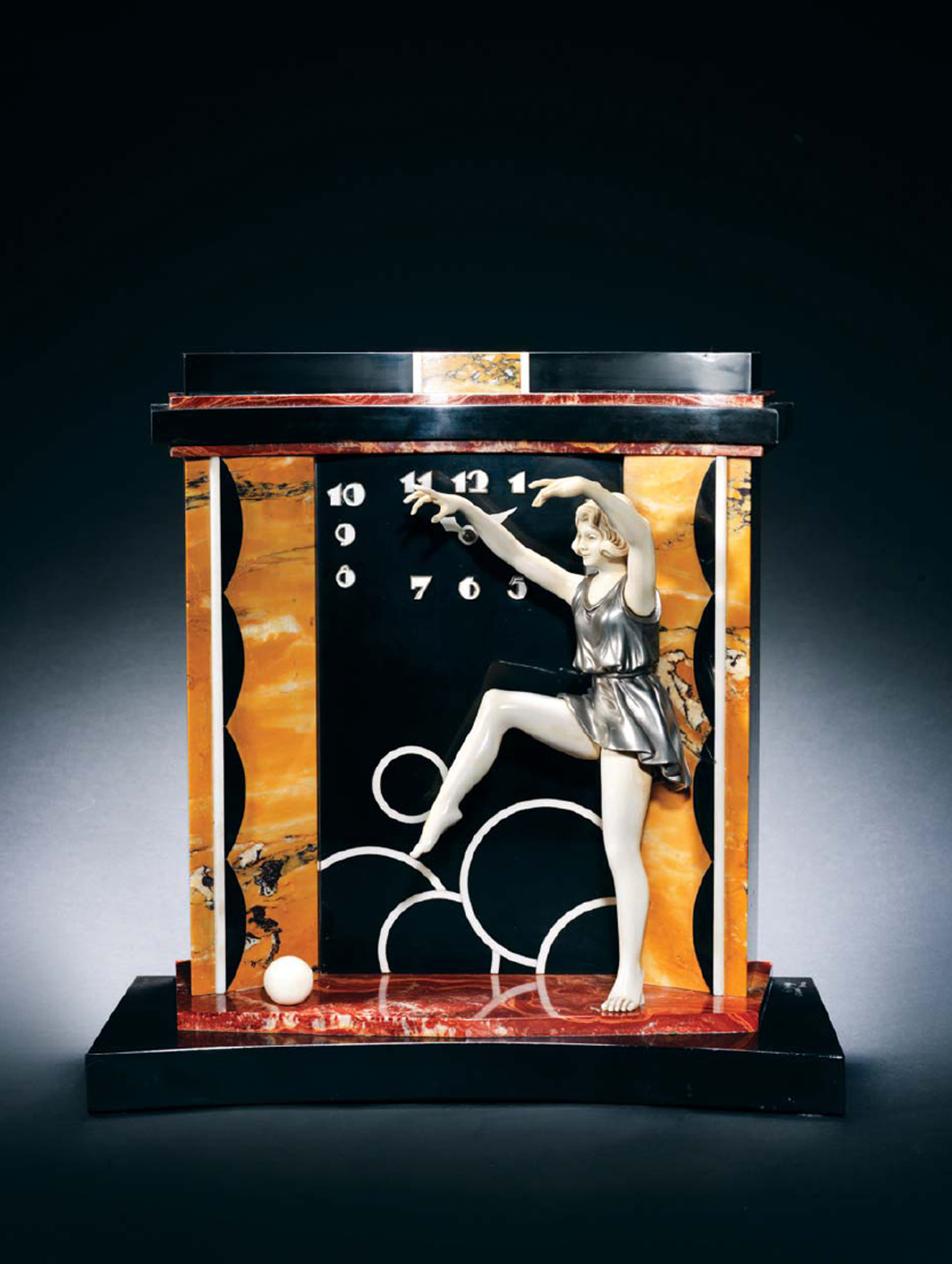

A cold-painted carved-ivory marble clock, c. 1930, by Armand Godard for Etling of Paris. The young female dancer is in a short tunic and the marble clock face has stylish geometric detailing. Height 34.5 cm.

FOREWORD

I N 1968, WHEN I was twenty-eight, I wrote the first little book on Art Deco. I still have a soft spot for it, as it effectively popularised that name, on both sides of the Atlantic, for the decorative style of the inter-war years. I called Deco the last of the total styles something that influenced virtually everything, from powder compacts and letterboxes to luxury hotels and ocean liners.

But, like all pioneers, I made mistakes. Can you believe that I wrote a book on Deco with not a single mention or illustration of the pottery of Clarice Cliff? I really regret that. Also at that stage I had not seen any of the great Deco buildings of New York or Los Angeles, which now strike me as the finest flowering of the style. All that changed when I was asked to organise a huge Deco exhibition in Minneapolis for the summer of 1971. I met Sonia Delaunay, Andy Warhol and Barbra Streisand, all of whom lent classic Deco from their collections. Streisand was so late for our appointment that I missed my plane home. I later realised that Streisand is an anagram of tardiness.

Since those early days of Deco scholarship, dozens, if not hundreds, of books have been published on every aspect of the style silver, china, glass, architecture, jewellery, plastics, you name it. Eric Knowles has had the benefit of all those studies. But, more than that, he has lived with Deco, as a leading auctioneer and one of the nations favourite experts on the Antiques Roadshow television programme.

You only need to watch him in action to realise that Eric is not only deeply knowledgeable but has absorbed the very essence of Deco and has a love for the artefacts that goes way beyond bookish scholarship. To him, its surviving relics are not just works of decorative art or collectables. They are talismans that conjure up that time which Noel Coward characterised as cocktails and laughter even if the period was also coloured by the rise of totalitarianism and the other darker aspects of the era.

For the beginner collector of Deco and even for collectors who have spent years amassing Deco objects, Erics sparkling text offers a unique introduction to the period and its dominant style, gloriously amplified by the rich illustrations. It is a delectable feast, by someone who not only knows his onions, but knows how to serve them in the most appetising way possible.

Bevis Hillier

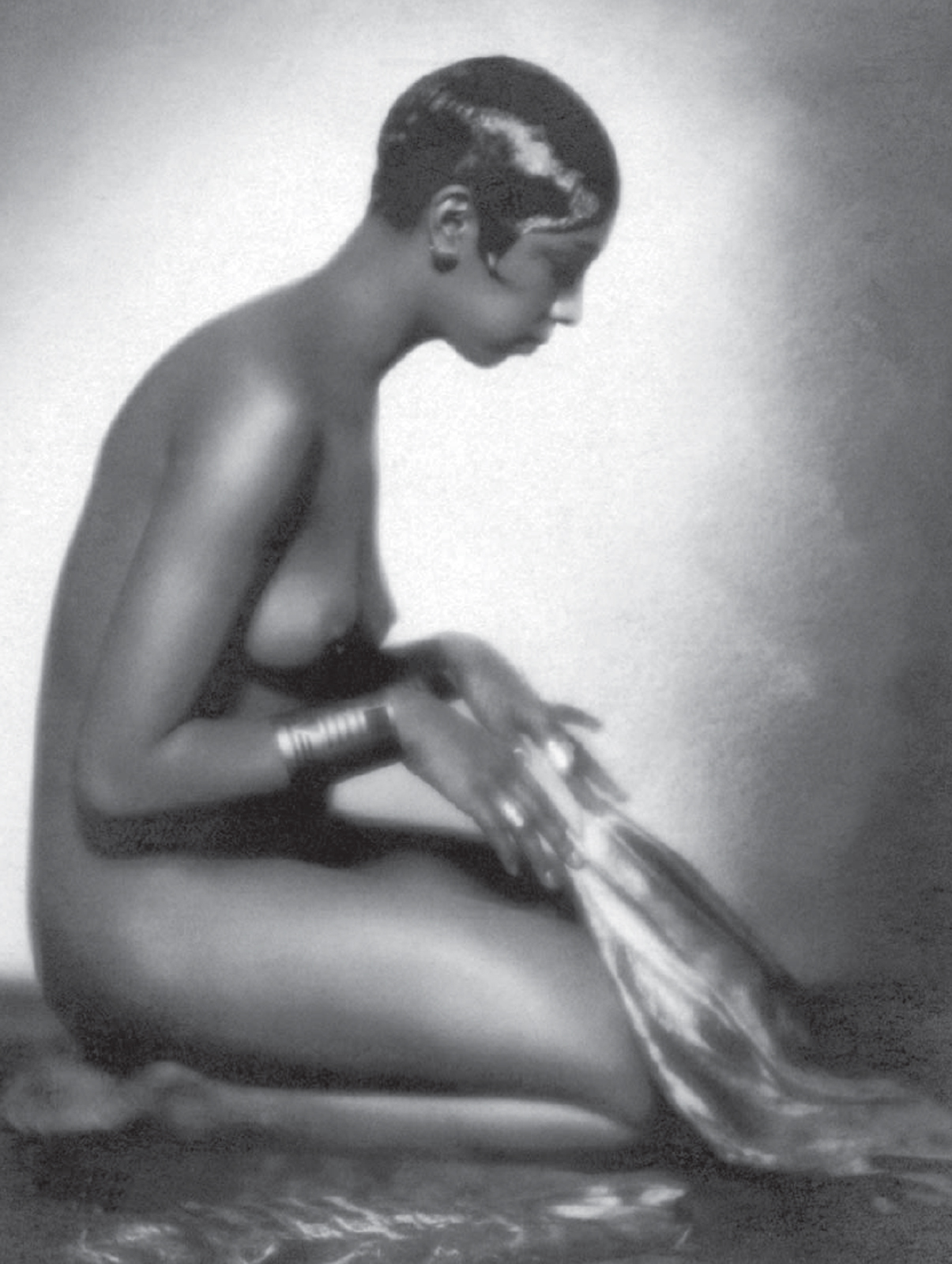

Photographic portrait study of Josephine Baker c. 1928. (Getty)

INTRODUCTION

I T WAS THE age of skyscrapers, air travel, fast cars and luxury liners, one forever associated with bobbed hair, shimmy dresses, cocktails, jazz music, and lively American dances typified by the Charleston not forgetting the sultry tango introduced from Latin climes. It was the age of the Schneider Trophy and of pioneering aviators such as eminent Americans Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart and Britains Amy Johnson.

It should also be remembered as an age when above all else it was important to keep young and beautiful that is of course if you trusted in the rest of the lyrics and wanted to be loved, while striving like a certain Millie to be perceived as being nothing less than thoroughly modern.

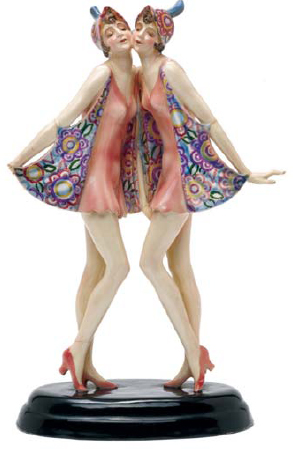

It was the age of Josephine Baker and Mistinguett, not forgetting a suave Maurice Chevalier and the alluring Dolly Sisters. Janszieka and Roszicka Deutsch known as Rosie and Jenny were Hungarian twins raised in New York who found international fame as dancers. They toured the United States with the Ziegfeld Follies and performed in Paris at the Moulin Rouge and the Casino de Paris as well as other leading European venues. Several deep-pocketed members of the social elite were to succumb to their alluring personality, and both married wealthy patrons and lived a life of total luxury, amassing large fortunes at the casino tables and accumulating lavish jewellery collections.

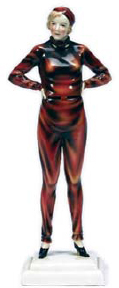

Goldscheider pottery figure of Amelia Earhart, c. 1930, modelled by Stefan Dakon, the aviator in flying suit and beret with goggles around her neck. Height 38.5 cm.

It was the age of Hollywood, when the Silents were to give way to the Talkies introducing a constant parade of glamorous film stars to an insatiable public on both sides of the Atlantic, as epitomised by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. It was the age when women swooned at the very sight of Rudolf Valentino, while both sexes marvelled at the Busby Berkeley song-and-dance spectaculars, performed on an epic scale and aided by inventive camera angles and a chorus line of leggy lovelies.

Goldscheider pottery of The Dolly Sisters, the dancers modelled cheek-to-cheek and wearing short tunic dresses and feathered headgear; c. 1925. Height 39 cm.

It was the age of geometric decorative motifs such as the chevron, the zig-zag, the lightning bolt and the coloured and leaded glass sunburst motifs that offered the promise of a brighter tomorrow in many a suburban home of the time.

Above all else, it was the age of the machine, with the fear of its potential played out in the futuristic prophecy of Fritz Langs film Metropolis, set in a densely built city that parodied the emerging skylines of New York and Chicago.

Portrait of the Dolly Sisters (see also ).

Following the mayhem of the First World War, it was also an age of great expectations, epitomised by a growing optimism and by a party atmosphere that roared right through the 1920s until the Wall Street Crash of 1929 brought the festivities to an abrupt halt and ushered in the Depression, and with it years of international political uncertainty and financial suffering for millions. Ensuing events led inexorably to yet another unwanted world war, come the fateful year of 1939.

Both Europe and America had emerged from the war clouds of 1918 with the structure of society irrevocably altered. Not least was the emergence of the nouveaux riches who had benefited from the needs and misfortunes of others but whose dealings had not gone unnoticed in the contemporary observations of such writers as Siegfried Sassoon.

However, it was role of women in the war, not only serving their country but also advancing towards emancipation and eventually the right to vote, that might be considered the most profound social outcome. The modern woman was to bear little resemblance to the ethereal