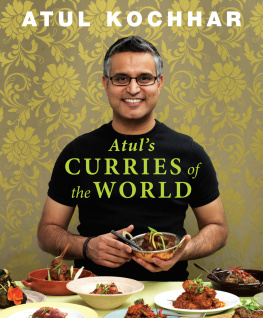

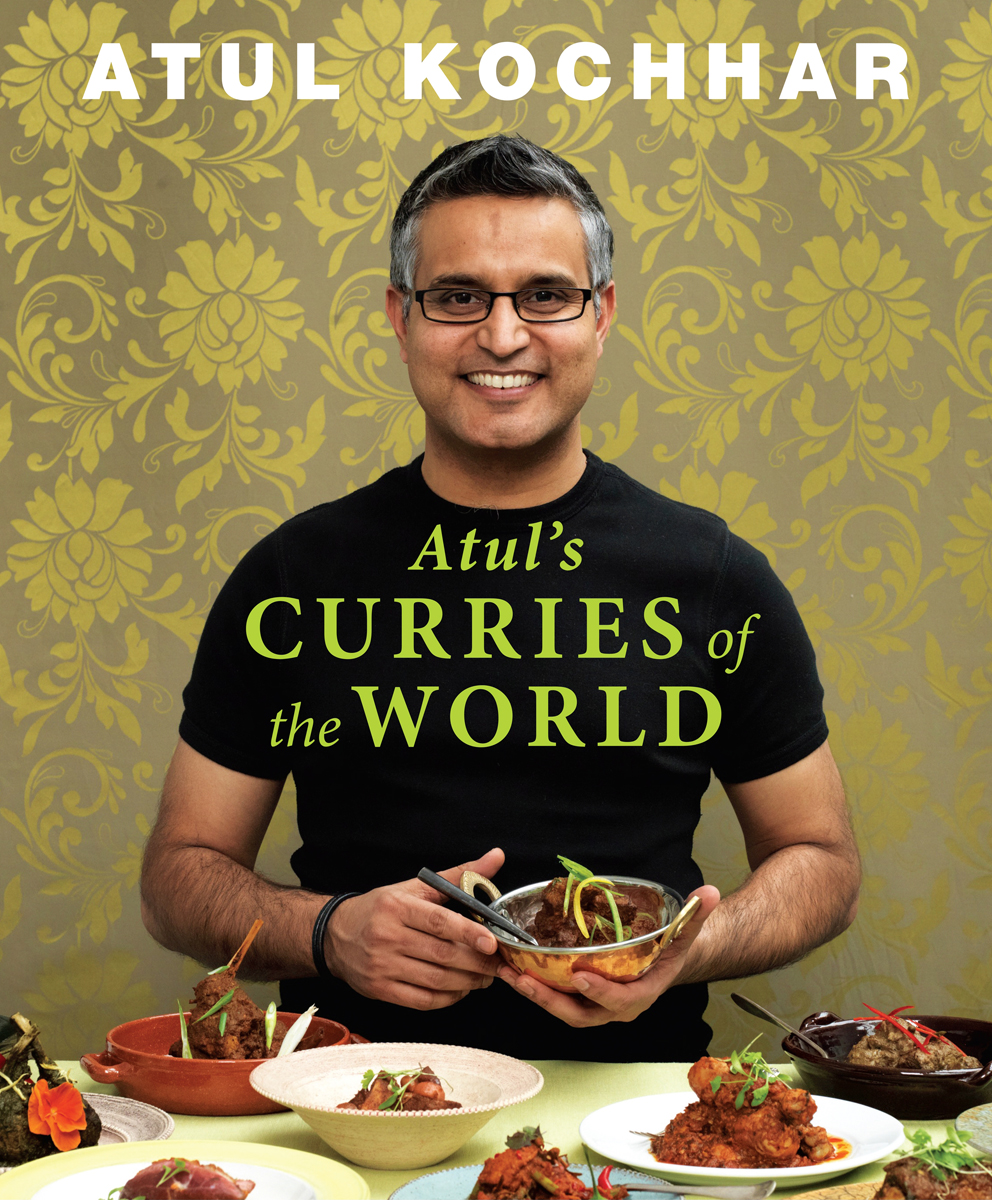

This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Absolute Press, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Absolute Press Scarborough House 29 James Street West Bath BA1 2BT

Phone 44 (0) 1225 316013

Fax 44 (0) 1225 445836

E-mailwebsite www.absolutepress.co.uk Text copyright Atul Kochhar, 2013 This edition copyright Absolute Press Photography copyright Mike Cooper

Publisher Jon Croft

Commissioning Editor Meg Avent

Art direction and design Matt Inwood

Editor Imogen Fortes

Assistant Editors Norma Macmillan and Gillian Haslam

Indexer Zoe Ross

Photography Mike Cooper

Food Styling Atul Kochhar

ISBN: 978-1-9066-5079-7

ePub: 978-1-4729-3277-8 The rights of Atul Kochhar to be identified as the author of this work have been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library. To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square London WC1B 3DP www.bloomsbury.com

A note about the text This book is set in Minion and Helvetica Neue.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square London WC1B 3DP www.bloomsbury.com

A note about the text This book is set in Minion and Helvetica Neue.

Minion was created by Robert Slimbach, inspired by fonts of the late Renaissance. Helvetica was designed in 1957 by Max Miedinger of the Swiss-based Haas foundry. In the early 1980s, Linotype redrew the entire Helvetica family. The result was Helvetica Neue. I would like to dedicate this book to my mother, Mrs. Kochhar. Kochhar.

Throughout my journey, my father was my inspiration; my mother has been my strength. She was my teacher at school and my mother at home but more importantly, a very good friend who I could talk to in all my hours of need. Her strong will has given me and my siblings a strength and belief that we can achieve anything that we desire. My journey from home to here has had lots of doses of encouragement from her words, such as: Success without struggleis absolutely useless; Believe in yourself and peoplewill believe in you; Failure is a very importantfeeling to be able to enjoy success. All of these have had a deep impact on my formative years. I hope that I can pass my mothers values on to my own children and guide them as she has guided me through life as a brilliant parent and as an amazing friend.

Thank you for being there when I need you most. Mom! I love you! C ONTENTSI NTRODUCTION It is now widely acknowledged that a chicken tikka masala trounces good old fish and chips and steak and kidney pie as the winner of Britains favourite dish. But aside from knowing that the dish sits alongside an Indian repertoire and is generally found in a curry house, have any of us ever stopped to think about the origins of the dish and why we have developed such a love of spiced food in this country? Where does our relationship with the curry come from and why is knocking up a Thai green curry so different to sitting down to an Indonesian korma (see all at their base curry dishes? This book aims to answer all these questions but above all to share with you my recipes for this wonderful dish and its countless interpretations. Even the very meaning of the word curry causes confusion and is often misinterpreted. In the UK, the use of the term appears to date from the mid-seventeenth century, around the time of the spice trade, when British merchants first encountered spiced food on their travels to Asia and adopted the word to denote any type of savoury dish that was prepared using spices. In India, a curry refers to something more specific: it is a spiced dish with a sauce or gravy or masala base.

Other spiced food would never be referred to as curry. Yet to confine it to such a simplistic definition would be a misrepresentation of the complexities of the dish. For a curry is part of an Indian cuisine that has been influenced by over 5,000 years of a rich and diverse history, involving interaction with many different cultures and religions. The Indian ability to adopt and adapt has meant that the cuisine has changed accordingly and has been enriched by the ingredients and eating habits of these exchanges; but it has also meant that other cultures and nations have borrowed from Indian customs, the result of which has been the creation of curry dishes of their own. The modern-day curry is thus a global term to describe the culmination of this past and now includes manifold varieties across the world. You will find that throughout the book I have often referred to the Indian subcontinent, rather than just to India, by which I mean the entire historical region prior to the Partition of India and Independence in 1947 (modern-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka).

From a culinary perspective this is how it needs to be considered as much of the traits and influences I describe pre-date todays frontiers. Similarly, within the subcontinent it is common to distinguish between the North and South in terms of their styles of cuisine, while also acknowledging that within that there are innumerable variations according to region, religion and culture. Very broadly speaking, the commonly used spices are perhaps the biggest distinguishing factor. In the North, favoured spices include coriander, cumin, turmeric, chilli powder, cardamom, cloves, cinnamon and fennel warming, colourful spices that bring visual vibrancy as much as heat and flavour. In the South, curry leaves, tamarind, fenugreek, chilli and peppercorns dominate giving rise to some of Indias spiciest dishes. Northern Indians tend to prepare their whole spice mixes (khada garam masala) and add it to the pan at the beginning of cooking then layer the other elements of the dish around it, while in southern India, the spices may be added towards the end of cooking as spice powders (or podi) sometimes being fried in oil separately (known as a tarka in the North) and simply poured over the dish right at the end.

Naturally, the styles of cuisine are influenced by the geography and produce of the regions. Southern Indian food leans heavily towards seafood so it is that Goans enjoy fabulous coconut-laden fish curries; and while northern Indians favour unleavened breads as their main starch (this region is home to the tandoor oven and thus to tandoori naan and roti, and parathas), no southern Indian meal would be complete without rice. Rice is the base around which the meal is built and only one curry should be tasted with each mouthful of rice in order to appreciate the individual spicing of each dish. Trade and colonisation have played a huge part in the evolution of the curry. The use of native spices on the Indian subcontinent can be traced as far back as pre-historic times yet it is really once the trade of spices began that we can start to see some of the culinary divisions and variations emerge and the birth of the styles of regional cuisine we can distinguish today. The early sixteenth century saw the establishment of the Mughal, or Mughlai, dynasty across the northern Indian subcontinent.

This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Absolute Press, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Absolute Press Scarborough House 29 James Street West Bath BA1 2BT Phone 44 (0) 1225 316013 Fax 44 (0) 1225 445836 E-mailwebsite www.absolutepress.co.uk Text copyright Atul Kochhar, 2013 This edition copyright Absolute Press Photography copyright Mike Cooper Publisher Jon Croft Commissioning Editor Meg Avent Art direction and design Matt Inwood Editor Imogen Fortes Assistant Editors Norma Macmillan and Gillian Haslam Indexer Zoe Ross Photography Mike Cooper Food Styling Atul Kochhar ISBN: 978-1-9066-5079-7

This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Absolute Press, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Absolute Press Scarborough House 29 James Street West Bath BA1 2BT Phone 44 (0) 1225 316013 Fax 44 (0) 1225 445836 E-mailwebsite www.absolutepress.co.uk Text copyright Atul Kochhar, 2013 This edition copyright Absolute Press Photography copyright Mike Cooper Publisher Jon Croft Commissioning Editor Meg Avent Art direction and design Matt Inwood Editor Imogen Fortes Assistant Editors Norma Macmillan and Gillian Haslam Indexer Zoe Ross Photography Mike Cooper Food Styling Atul Kochhar ISBN: 978-1-9066-5079-7