Suzanne Marrs - What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell

Here you can read online Suzanne Marrs - What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell

- Author:

- Publisher:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Suzanne Marrs: author's other books

Who wrote What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE CORRESPONDENCE OF

Eudora WeltyandWilliam Maxwell

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT

BOSTON NEW YORK

2011

Copyright 2011 Suzanne Marrs, Emily Brooke Maxwell and

Katharine Farrington Maxwell, and Eudora Welty, LLC

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Welty, Eudora, 19092001.

What there is to say we have said : the correspondence of

Eudora Welty and William Maxwell / edited by Suzanne Marrs.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-547-37649-3

1. Welty, Eudora, 19092001 Correspondence.

2. Maxwell, William, 19082000 Correspondence.

3. Authors, American20th centuryCorrespondence.

I. Marrs, Suzanne. II. Title.

PS 3545. E 6 Z 48 2011

813'.52dc22

[B]

2010042105

Book design by Greta D. Sibley

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Permissions credits appear on .

To Timothy Seldes

INTRODUCTION

1. "Never Lose Letters from an Editor": 19421943

2. "Wonderful to Be a Writer. Wonderful to Grow Roses.

Wonderful to Care": 19431954

3. "Similar Discoveries": 19541959

4. "Stubborn Enough to Be a Writer": 19601966

5. "Your Heart Down on Paper": 19661970

6. "So Much Honor Coming Down on My Head": 19711980

7. "What There Is to Say We Have Said": 19811996

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

INDEX

LETTERS, reading them and writing them, claimed the rapt attention of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell throughout their adult lives, and books of letters by fellow authorsLord Byron, Anton Chekhov, Roger Fry, William Faulkner, Robert Louis Stevenson, and H. L. Mencken, for instancethey found particularly engaging. In 1983, Maxwell collected and edited a book of his friend Sylvia Townsend Warner's letters, and eight years later Welty included many letters when she coedited The Norton Book of Friendship. In the introduction to that book, she noted:

All letters, old and new, are the still-existing parts of a life. To read them now is to be present when some discovery of truthor perhaps untruth, some flash of lightis just occurring. It is clamorous with the moment's happiness or pain. To come upon a personal truth of a human being however little known, and now gone forever, is in some way to admit him to our friendship. What we've been told need not be momentous, but it can be as good as receiving the darting glance from some very bright eye, still mischievous and mischief-making, arriving from fifty or a hundred years ago.

For both Welty and Maxwell, letters provided a way of expanding the range of their friendships. Letters provided a more comprehensive sense of the person who, whether or not that person was someone they had actually known, stood behind the stories, poems, and essays they valued or found interesting. Although Welty and Maxwell awarded letters a modest place in the hierarchy of literary genres, it was a place of importance to them. So it is not surprising that in 1976, when a second volume of Virginia Woolfs letters came into print, both Welty and Maxwell, two longtime admirers of Woolf and two of America's most distinguished fiction writers, separately reviewed the book.

These reviews (by two old friends whose literary opinions rarely diverged) struck dissonant tones but had a common focus. Welty opened her review by quoting from Woolfs novel Jacob's Room: "Life would split asunder without letters." That statement, Welty went on to suggest, described the role correspondence played not only for Woolf's characters but also for the writer herself. "A need for intimacy," Welty asserted, "lies at the very core of Virginia Woolf's life. Besides the physical, there are other orders of intimacy, other ways to keep life from splitting asunder. Lightly as it may touch on the moment, almost any letter she writes is to some degree an expression of this passion, of which the eventual work of art was The Waves." To Welty, even letters filled with lacerating wit were a way of reaching for connection.

Maxwell did not fully agree with this assessment. Instead of discussing a desire for intimacy in Woolf's letters, he described a lack of self-assurance: "Even though Virginia Woolf was, I think, a writer of the first rank, she could not rest secure in the knowledge of her talent; the prevailing tone of the letters written in her maturity is disparagement." Particularly distasteful to Maxwell was Woolf's habit of ridiculing others, and he felt that "strangers get off lightly compared to what happens when she is writing about friends." Though he sought to avoid moral judgments based on material not intended for publication and though he recognized that no friendship is without its prickly moments, Maxwell felt that Woolf could take "pleasure in being cruel." Still, there were letters of a different sort, and Maxwell particularly lauded one that Welty also admired. In that 1922 letter, Woolf acknowledged her own vulnerability to doubt and sent encouragement to a young, then unpublished Gerald Brenan.

The Virginia Woolfs who emerged from the Welty and Maxwell reviews were strikingly different people, but undergirding both reviews was a belief that letters should be a way of embracing, supporting, and uniting with friends and that letters communicate most profoundly when they do not mask vulnerabilities. This shared belief is everywhere evident in the letters Eudora Welty and William Maxwell themselves wrote. "Orders of intimacy" other than the physical are often tragically missing from the lives of characters in their stories and novels. There the powerful need for friendship is typically defined by its lack. Not so in their correspondence.

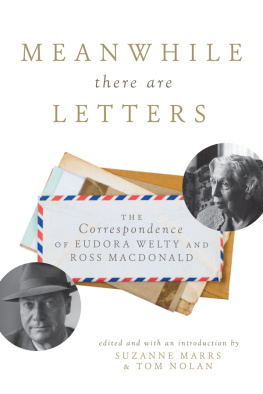

Welty shared intimate and voluminous exchanges of letters with many friends, including her agent Diarmuid Russell; fiction editor Mary Louise Aswell; childhood friend Frank Lyell; and the two men she loved over the course of her life, John Robinson and Ross Macdonald. Welty and these friends saved the letters they exchanged, and as her friends faced death, they stipulated that the letters Welty had written be returned to her. Although Welty at one point considered destroying these two-sided correspondences she came to possess, she ultimately willed them to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Maxwell's correspondence with friends was as extensive and generous as Welty's. He corresponded with fellow writers such as Frank O'Connor, Sylvia Townsend Warner, John Updike, John Cheever, and Larry Woiwode. He allowed his correspondence with Warner and O'Connor to be published. In the late 1990s, he gave his alma mater, the University of Illinois, a huge collection of his papers, including many letters from Eudora Welty. His estate has made his remaining letters from Welty available for this book, and Maxwell's letters to her are preserved as digital scans at the Eudora Welty House, a museum in Jackson, Mississippi.

For more than fifty years, Welty and Maxwell wrote to each other, sharing their worries about work and family, their likes and dislikes, their griefs and joys, their moments of despair and hilarity. Reading their letters admits us into the friendship of these two intellectual, imaginative, and erudite individuals. We learn that they were great in-takersat times fascinated, at times appalled by the world about them, but always describing it vividly with deft turns of phrase. Their letters often sparkle with humor, but their humor can also take on an ironic dimension. A generosity of spirit pervades the correspondence but is never saccharine. Although literary friendships are famous for going bad, Welty and Maxwell weathered inevitable moments of discontent. Issues of jealousy, resentment, cruelty, or condescension never threatened their relationship, which began in 1942, deepened over time, and found eloquent expression in their letters. In those letters, neither engaged in posturing or affectation. Instead, they both achieved the "triumphant vulnerability" that can result from daring to trust, empathize, and communicate.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell»

Look at similar books to What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.