Table of Contents

Praise for award-winning writer Eugene LindensThe Parrots Lament

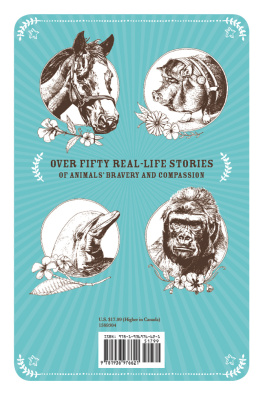

Linden offers entertaining examples of animal behavior ranging from the humorous to the sorrowful ... [His] respect and love for all creatures in the animal kingdom is infectious ... His incisive, informal prose turns even these nonhuman scoundrels into endearing subjects.

The New York Times Book Review

In The Parrots Lament, Eugene Linden reveals how animals demonstrate aspects of intelligence as they escape from, cheat, and outfox humans.

Time magazine

The cumulative impact of these accounts, when interwoven with the authors distillation of the relevant ethological theories, creates a compelling argument in favor of consciousness in animals.

Booklist

If the scientific community remains skeptical about the quality of animal intelligence, Linden leaves no doubt about where he stands. He accepts evidence of animal consciousness and, at the end of his brisk, detailed report, so will many readers.

Publishers Weekly

An award-winning writer on science, nature, and the environment for Time magazine, National Geographic, and other publications, EUGENE LINDEN is the author of six books, including the landmark study Apes, Men, and Language, New York Times Notable Book Silent Partners, and The Future in Plain Sight: Nine Clues to the Coming Instability. He has consulted for the U.S. State Department, the United Nations Development Program, and is a widely traveled speaker and lecturer. Mr. Linden has donated a portion of his royalties from The Parrots Lament to the Humane Society of the United States and to Traffic, a branch of the World Wildlife Fund dedicated to stopping the trade in endangered species.

For Mary

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MY greatest debt is to my parents and most particularly my mother, Gloria Linden, who from my earliest years brought to life for me the individuality and personality of the animals we encountered in the course of the day. This environment of rampant anthropomorphism left a lasting imprint on me, manifested in high school when I chose as my subject for a paper on Greek mythology the minor demigod Melampus, whose singular gift was that he could talk to the animals.

Ive been writing about animals and whether they could talk or think ever since. In the twenty-eight years since I began work on Apes, Men, and Language, Ive had the benefit of conversations and guidance from hundreds of scientists, trainers, and keepers, many of whom I have acknowledged and cited in previous books and articles.

Still, I would like to single out a few scientists and animal people who showed particular willingness to help me understand some of the intelligence, virtues, and vices of various animals. These include Beth Armstrong, Gail Laule, Maureen Fredrickson, Charlene Jendry, Gigi Ogilvie, Rick Glassey, Helen Shewman, and Geoffrey Creswell.

The administrators and keepers at the Woodland Park Zoo, the San Diego Zoo, the Bronx Zoo, the Columbus Zoo, the Tulsa Zoo, and ZooAtlanta, were particularly helpful and cooperative, as were the officials of the American Zoo and Aquarium Association, the American Veterinary Medicine Association, the International Society for Behavioral Ecology, and the Society for Interative and Comparative Biology. Many thanks to Leon Levy and Shelby White, who provided a perfect place for me to hole up when I was making the final revisions to the manuscript. Thanks also to Katherine and Aubrey Buxton, who brought to my attention the extraordinary story of Harriet the leopard.

In the course of this book I revisited a number of scientific and philosophical issues that I have written about previously, and I would like to thank James Gould, Richard Byrne, Sally Boysen, Lyn Miles, Donald Griffin, Thomas Sherratt, Karen Pryor, William Conway, Gail Patricelli, Daniel Dennett, Steve Nowicki, Marion East, and Heribert Hofer for their insights and wisdom.

The book also benefited from the competence and professionalism of the people at Dutton. Id like to thank Claire Ferraro for supporting the book every step of the way, Karen Lotz for her superb editing and boundless intelligence, and Karens assistant, Amy Wick, for fielding problems, questions, and requests way beyond the call of duty. I must thank David Bjerklie for making sure I policed the text for unjustifiable assumptions (a difficult job in a book whose very premise is unjustifiable in the view of some scientists). I would like to thank Cary Ryan for giving me the benefit of her keen eye for lapses in internal logic. And, as always, I would like to thank Esther Newberg for providing me and the book with the best possible representation.

Finally, if a little sentimentality can be permitted, I have to thank the many pets who have come and gone in my life, starting with Cinders, my childhood cat; Zephyr, the heroic Maine Coon cat; Murghatroyd, Philo, and Junior, our present Bengals, and Caruso, an ancient and wise stray cat in our neighborhood who somehow has made friends with all the people on our street even while beating up all of our pets. All have told me something about what it is like to be an animal. Even Bully, my giant bullfrog who, when I was ten, ate all the other frogs in his enclosure, was telling me something, although Im still not sure what particular message he was trying to get across.

PREFACE

ANIMALS appear in so many guises in various aspects of my writing that if a psychiatrist ever got me into analysis, he or she might reasonably assume that apes, dolphins, elephants, birds, felines, and canines have some totemistic importance in my worldviewthat in our fellow creatures I see embodiments of every aspect of the human situation. The shrink would be right, of course. Thats exactly how I view the world. How we treat animals in captivity reflects on our view of ourselves and our humanity. How we treat wild nature gives us insight into whether we are going astray in our dealings with the rest of the natural order.

The course of my writing has taken me to the far corners of the globe, and animals pop up even when my purpose is to write about entirely different matters. For instance, I went to Antarctica in the fall of 1996 with the ostensible mission of writing about the relationship of the frigid continent to the global climate system. Once there, however, I found one of the more compelling ways to convey the delicate balance of climate and life in this extreme environment was to look at the impact of an early breakup of the McMurdo Sound sea ice on the population of emperor penguins. That Antarctic summer, the sea ice broke up two weeks early, forcing fledglings to begin their wanderings through the Southern Ocean before they were ready to embark, probably dooming most to an early death.

More often when Ive headed off to some remote place, Im specifically looking for animals. Ive been to places in central Africa where the animals have never before encountered humans, and Ive been to places in southeast Asia where scientists are discovering large animals previously unknown to science. Ive visited almost every major research station for studying the great apes in the wild. Ive traveled to rain forests in Borneo, India, and various parts of the Amazon to report on the loss of biodiversity as we humans crowd countless species into extinction.