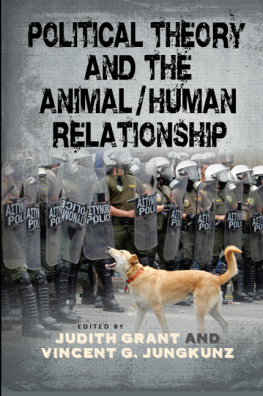

COVER: A dog barks at a formation of riot police near the Greek parliament in Athens, June 15, 2011. REUTERS/Pascal Rossignol.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2016 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Jenn Bennett

Marketing, Anne M. Valentine

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Political theory and the animal/human relationship / edited by Judith Grant and Vincent G. Jungkunz.

pages cm. (SUNY series in new political science)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5989-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4384-5990-5 (e-book) 1. Animals (Philosophy). 2. Human-animal relationshipsPhilosophy. 3. Human-animal relationshipsPolitical aspects. 4. Power (Social sciences) I. Grant, Judith, 1956 II. Jungkunz, Vincent.

B105.A55P65 2016

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Introduction

The Importance of the

Animal/Human Question

for Political Theory

JUDITH GRANT AND VINCENT G. JUNGKUNZ

T raditionally, political thinking has separated mankind from animals in that it has understood and accepted humans as fundamentally different from and dominant over other animals. Modern technologies and political developments have left nonhuman animals more, and potentially less, vulnerable to the whims, fancies, desires, and needs of human animals, as well as to the continuing environmental changes on which all sentient beings depend for survival. The discipline of Western political theory has been rooted in a canon that ranged from Plato to Marx; this canonical understanding conceptualized politics as an anthropocentric activity. In some ways, it continued in the Aristotelian vein by defining political engagement and thinking as at least linked to, if not actually defining, what it means to be human. Self-consciousness was linked to Reason in that self-consciousness required the ability both to formulate abstract thoughts and to have an understanding of an individual self as distinct from the species. In virtually all of the humanist philosophies in which political theory finds its roots, language and grammar have also

This human exceptionalism turns on the difference between the brain and the mind, as thinkers as far back as Aristotle have indeed contended. For while all animals, it has been argued, have the former, only humans have the latter. Likewise, instinct is different from and inferior to reason. While instinct traps animals in a servile relationship to their restrictive natures as well as to nature as a whole, it is reason that enables humans to control their own destinies, and to conquer the natural world, including of course, animals. Ideally, the body and its needs must be transcended by the mind, which, when freed from its base animality, can access the Universal, justice, wisdom, truth, and all the rest of the baggage of the rationalist humanist tradition.

The use of the male pronoun in the above summary is not accidental, as the tradition holds that not all humans possess these qualities in equal measure. The rub has always been that the very features that defined man were almost immediately turned back against him to divide and create hierarchies within the human species. For not all humans possessed the full complement of those most essential human traits, and most fell somewhere on a continuum between those who could achieve mankinds highest potential (i.e., free-born men) and the line that was drawn somewhere just above the animal. As Kant wrote about womens inferiority, it is not enough to keep in mind that we are dealing with human beings; we must also remember that they are not all alike.

The emergence of racialized slavery, as well as the perpetuation of modern racism, was and is, substantially constituted through the animal/human binary. Slaves were dehumanized, as were free blacks, in the postCivil War United States. Notions of animalistic and savage have been deployed in efforts of social control surrounding differential racialization of nonwhite groupings. The animal/human binary has had an enduring and broad influence on what humans are, how power meanders, and what we do to one another. About Africans, Kant writes in a similar vein, but with more vitriol: The Negroes of Africa have by nature no feeling that arises above the trifling. Mr. Hume challenges anyone to cite a single example in which a Negro has shown talents, This ploy demonstrates, of course, the role of the animal in making the case for differentiations among humans.

This rationalist/humanist discourse has been thoroughly trounced, interrogated, and deconstructed at least since Nietzsche: What is humanism but a bladder full of hot air? Decades of work in feminism, multiculturalism, queer theory, structuralism, and poststructuralism show that political theorists, along with the rest of academia, are well acquainted with many varied and trenchant critiques of rationalist humanism. Still, until relatively recently, the animal/human distinction continued to be treated as axiomatic, even though it was, in many ways, the cornerstone of humanism. In this way, even many of the staunchest critics of humanism remained anthropocentric.

Since the 1970s, the field of animal studies has become an increasingly important part of academia, especially in fields such as philosophy, literary studies, and law, though it has remained relatively distinct from those social theoretical critiques of humanism made familiar by structuralists, multiculturalists, and the rest. Exceptions to this include works by Giorgio Agamben and Jacques Derrida, which have been concerned with the way in which the human has been produced in relation to the animal. At least one reason why Singers work made such an impact is that philosophers had so often rooted the category human in rationality. That is, to gain entry into a host of rights, privileges, duties, responsibilities, and protections reserved for humans, a being had to pass muster as rational. The task for animal rights, therefore, was to find empirical proof of animal rationality. Singer changed the terms of this discussion.

Humanist theory has been grounded in a rationalist, foundationalist epistemology that explicitly and repeatedly excises animals from the moral universe on the grounds that they were not rational, and thus not human. Worse, they were the functional equivalent of things. Even if humans were more or differently rational, Singer argued, rational superiority could not legitimately be used as an ethical justification for the kinds of torture and casually acceptable death perpetrated on animals by humans. He used the term speciesism to critique arguments about human exceptionalism, and the beliefs and actions that follow from it. Insofar as speciesist claims began from an axiom about the inherent superiority of humans over animals, he argued, speciesism, like racism and sexism, denoted an arbitrary hierarchy that was held in place by power while masquerading as a natural order.