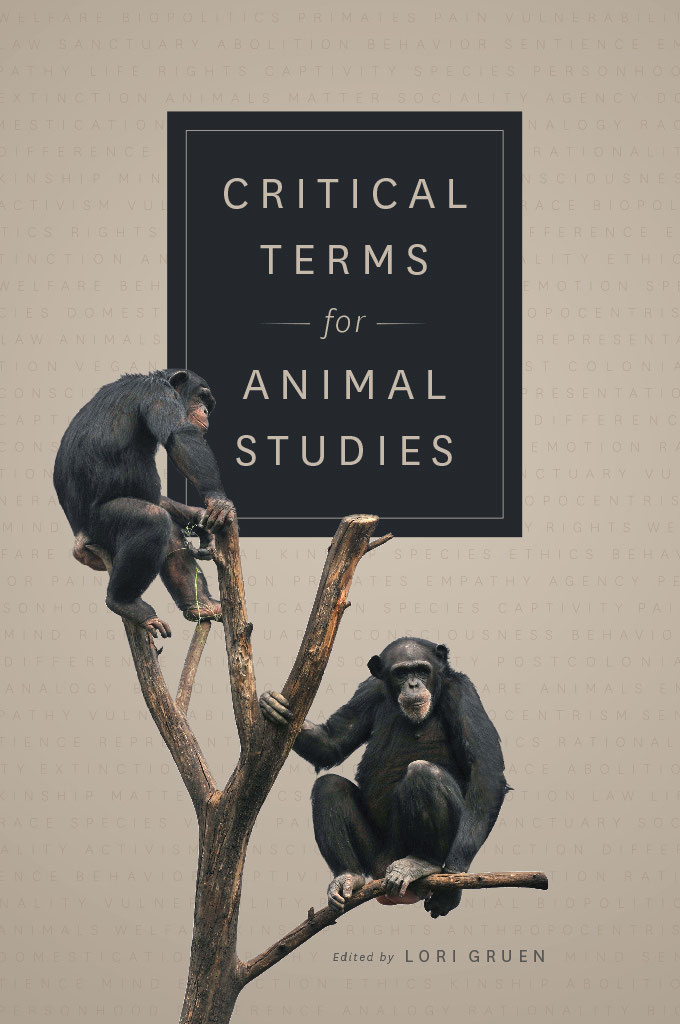

CRITICAL TERMS for ANIMAL STUDIES

CRITICAL TERMS for ANIMAL STUDIES

Edited by LORI GRUEN

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2018 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-35539-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-35542-9 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-35556-6 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226355566.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gruen, Lori, editor.

Title: Critical terms for animal studies / edited by Lori Gruen.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018008776 | ISBN 9780226355399 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226355429 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226355566 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Human-animal relationships. | AnimalsSocial aspects. | Animals (Philosophy). | Human-animal relationshipsMoral and ethical aspects. | Animal rights. | Cognition in animals.

Classification: LCC QL85 .C75 2018 | DDC 591.5dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018008776

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

10 Ethics Alice Crary

11 Extinction Thom van Dooren

12 Kinship Agustn Fuentes and Natalie Porter

13 Law Kristen Stilt

14 Life Eduardo Kohn

15 Matter James K. Stanescu

16 Mind Kristin Andrews

17 Pain Victoria A. Braithwaite

18 Personhood Colin Dayan

19 Postcolonial Maneesha Deckha

20 Rationality Christine M. Korsgaard

21 Representation Robert R. McKay

22 Rights Will Kymlicka and Sue Donaldson

23 Sanctuary Timothy Pachirat

24 Sentience Gary Varner

25 Sociality Cynthia Willett and Malini Suchak

26 Species Harriet Ritvo

27 Vegan Annie Potts and Philip Armstrong

28 Vulnerability Anat Pick

29 Welfare Clare Palmer and Peter Sande

Lori Gruen

Animal Studies is almost always described as a new, emerging, and growing field. A short while ago some Animal Studies scholars suggested that it has a way to go before it can clearly see itself as an academic field (Gorman 2012). Other scholars suggest that the discipline is a couple of decades old (DeMello 2012). Within cultural studies as well as the social sciences, there have been multiple attempts to locate the beginning of Animal Studies in the 1990s, and each proposed origin story is accompanied by specific aspirations for the field. The various hopes evoked by Animal Studies are part of what makes the field so exciting and at times contentious.

Histories

In one of the first journals dedicated to Animal Studies, Society and Animals, editor Ken Shapiro wrote in 1993 that the main purpose of the journal is to foster within the social sciences, a substantive subfield, animal studies. And he described this subfield as primarily concerned with providing a better understanding of ourselves; through animal studies we wish to understand our varied relations to them, and to assess the costseconomic, ethical, and most broadly, culturalof these relations (Shapiro 1993, 1). Social scientists also assessed the benefits of these relations, insofar as they existed, for both humans and other animals.

Around the same time that Society and Animals was launched, in literary studies, according to Robert McKay (2014), very few scholars were concerned with the near omnipresence of nonhuman animals in literary texts or how they formed part of a much longer story about creatural life that the humanities, in dialogue with other disciplines, could document and interpret(637). This paucity of attention may have been the result of a discomfort that emerges when, as Susan McHugh (2006) describes it, a systematic approach to reading animals in literature necessarily involves coming to terms with a discipline that in many ways appears organized by the studied avoidance of just such questioning. But that avoidance was beginning to dissipate by the late 1990s, when we find the peculiar correlation that gave birth to Animal Studies at that time: the commitment to developing both scholarly knowledge of an as yet unthought subject of inquiry (always a serious business) and also the responsibility needed to show the proper respect for, to take seriously as subjects of experience, the animals whose lives are represented in cultural texts (McKay 2014, 637). Cary Wolfe (2009) reflects further:

One would think animal studies would be more invested than any other kind of studies in fundamentally rethinking the question of what knowledge is, how it is limited by the over determinations and partialities of our species-being (to use Marxs famous phrase); in excavating and examining our assumptions about who the knowing subject can be; and in embodying that confrontation in its own disciplinary practices and protocols (so that, for example, the place of literature is radically reframed in a larger universe of communication, response, and exchange, which now includes manifold other species). (Wolfe 2009, 571)

Within the broad rubric of cultural studies, there was a different focus than that of the social scientists, and different types of questions were being asked. And even within cultural studies we can see tensions. Is the project of Animal Studies to take animal representations seriously within literature or to take animals seriously as subjects or to come to new understandings by recognizing the difficulties and possibilities of moving beyond the human as the only subjects of cultural knowledge?

Though these questions were being asked by a growing number of literary scholars, animals were not quite unthought subjects of inquiry in other disciplines. Important books had already been published: Donna Haraways Primate Visions (1989), Harriet Ritvos The Animal Estate (1987), Carol Adams The Sexual Politics of Meat (1990), and Donald Griffins Animal Minds (1992) are just a few, representing quite different perspectives on the question of the animal. The 1990s marks an important moment in the growth of work in Animal Studies to be sure, but I hesitate to call it the origin. Thinking about and with animals has been a central concern across a number of academic disciplines going back a very long time.

Within philosophy, for example, two of the most well-known scholars thinking about ethical and political obligations to other animals, Peter Singer and Tom Regan, published before the 1990s (Singers Animal Liberation first appeared in 1975 and Regans The Case for Animal Rights appeared in 1983), but animals as subjects of philosophical inquiry can be found all the way back to antiquity. Henry Salt, in his 1892 book Animal Rights: Considered in Relation to Social Progress, draws readers to his immediate questionif men have rights, have animals their rights also?and notes,

From the earliest times there have been thinkers who, directly or indirectly, answered this question with an affirmative. The Buddhist and Pythagorean canons, dominated perhaps by the creed of reincarnation, included the maxim not to kill or injure any innocent animal. The humanitarian philosophers of the Roman empire, among whom Seneca and Plutarch and Porphyry were the most conspicuous, took still higher ground in preaching humanity on the broadest principle of universal benevolence. (Salt 1892, 23)