Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

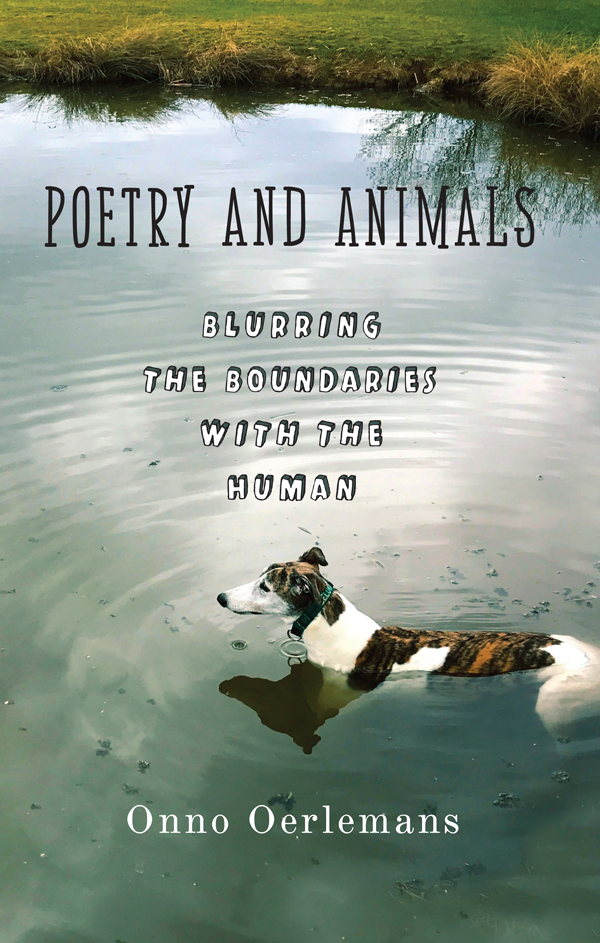

POETRY AND ANIMALS

POETRY AND ANIMALS

BLURRING THE BOUNDARIES with THE HUMAN

ONNO OERLEMANS

Columbia University

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54742-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Oerlemans, Onno, 1961 author.

Title: Poetry and animals: blurring the boundaries with the human / Onno Oerlemans.

Description: New York: Columbia University, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017049986 | ISBN 9780231159548 (cloth: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Animals in literature. | Exempla in literature. | Anthropomorphism in literature. | Human-animal relationships in literature. | Animal welfare in literature. | AnimalsSymbolic aspects. | Poetry, ModernHistory and criticism. | Poetry, MedievalHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC PN1083.A5 O37 2018 | DDC 809.1/9362dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017049986

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Julia Kushnirsky

Cover image: courtesy of the author

FOR SALLY

Nature poetry should not be taken to be avoiding anthropomorphism, but to be enacting it, thoughtfully.

Don McKay, Vis Vis

CONTENTS

I began this book with the realization that while poetry has helped me to see, explore, and understand the complexity of the nonhuman animals in the world around me, there has been relatively little written about the relationship between animals and poetry. I have been inspired too by the rise of animal studies in literature, philosophy, and cultural studies, finding myself in the usual situation of having personal passion and interest align to some degree with what is (or was) new in the world of criticism and theory.

Many people have helped me along the way. Andrew Peart, while a dazzling undergraduate at Hamilton College, worked with me early on to find and collect poems about animals. His deep knowledge of twentieth-century American poetry, and his insight into individual poems, helped me get the book under way and informs my discussions of several specific poems. Tobias Menely, now at UC Davis, has also contributed enormously to the book; discussions with him have deepened my understanding of what matters in thinking about the representation of animals in literature, and his published work has been influential in my own thinking. My colleagues at Hamilton College have given me enormous support, as has the college itself, in terms of sabbaticals and publishing subventions. Wendy Lochner, Christine Dunbar, and Michael Simon at Columbia University Press have also provided much assistance. The anonymous readers to whom they submitted my manuscript gave much valuable guidance as I revised the text.

I especially want to acknowledge and thank the many students at Hamilton who have taken classes with me in which I have discussed animals and their representation in various works of literature. I have tested out many ideas with them, and the ensuing discussions have helped me move forward in my work. The excitement they have had about the general topic and the specific works has sustained my confidence in my own project, and many of the insights I have gleaned from those discussions have made their way into this book.

I also want to thank my wife, Sally Cockburn, on whom I have tested my deepest convictions, including some of my most outlandish ideas. If they survived her rational examination, those ideas are still here. Living with her, and our many companion dogs, these past several decades has essentially formed who I am, complete with my interest in and respect for nonhuman life on the planet.

I n 1936 the scholar Elizabeth Atkins published an article in PMLA called Man and Animals in Recent Poetry. In her essay Atkins presents evidence that in American poetry written since the World War, one of the most significant new developments is now seen to be the fascination which animal life holds for the poet. She notes that in the literary journals she surveyed over a period of fifteen years, 236 poets had published earnest and philosophical poems about animals, and that these poems present intimate portraiture with fidelity of detail worthy of the old Dutch portrait painters. In contrast to the depictions of animals in poetry of the Victorian and romantic periods, she argues, this new animal poetry is carefully literal. With copious references to poets and poems, Atkins argues that poetry about literal (as opposed to allegorical) animals is a genuinely new phenomenon. She offers several reasons for the rise of this new kind of animal poetry: the Darwinian revolution and the awareness it brings of the evolutionary kinship between humans and animals; the influence of Emily Dickinson; that most readers of poetry live in cities and so feel the absence of actual animals in their lives; that World War I and the new science of psychoanalysis have offered plentiful evidence of a sick civilization, which spurs a turn to the soundness in the primitive life of the beasts; and that human interest in animals is in any case immemorial. Echoing a Shelleyan notion of the relationship between poetry and intellectual progress in society, Atkins insists that this new animal poetry simultaneously reflects and anticipates a more general cultural awareness of the significance of animals. So too Atkinss article impressively anticipates the recent rise of animal-oriented criticism, which is also a response to the Darwinian revelation of our evolutionary kinship with animals.

There is a paradox revealed in the essaythat although animals have been curious to us beyond the myriad ways in which we have used them, their own interests and actual nature have always been marginal and unrecognized. Our awareness of animals is simultaneously bound by human history and culture and outside of that history and culture, which is true too of animals themselves. Yet there may now be something new under the sun. That animal studies is now truly interdisciplinaryand includes history, philosophy, and literary and cultural studies, rather than being only a relatively lowly branch within biology and psychologymeans that there is a growing cultural awareness of what animals mean, of what the animal as a concept means, and that animals have some form of inalienable value to and for themselves. Recent developments in evolutionary psychology have contributed to this growing awareness as well, helping to narrow the seemingly unbridgeable gap between human and nonhuman versions of sentience. As Susan McHugh argues in a much more recent PLMA article, Animal studies researchers are united by a commitment not so much to common methods or politics as to the broader goal of bringing the intellectual histories and values of species under scrutiny. As Atkins helps us to see, this new academic culture is late on the scene, though it is no doubt driven by many of the reasons she identifies as giving rise to a new kind of poetry about animals.