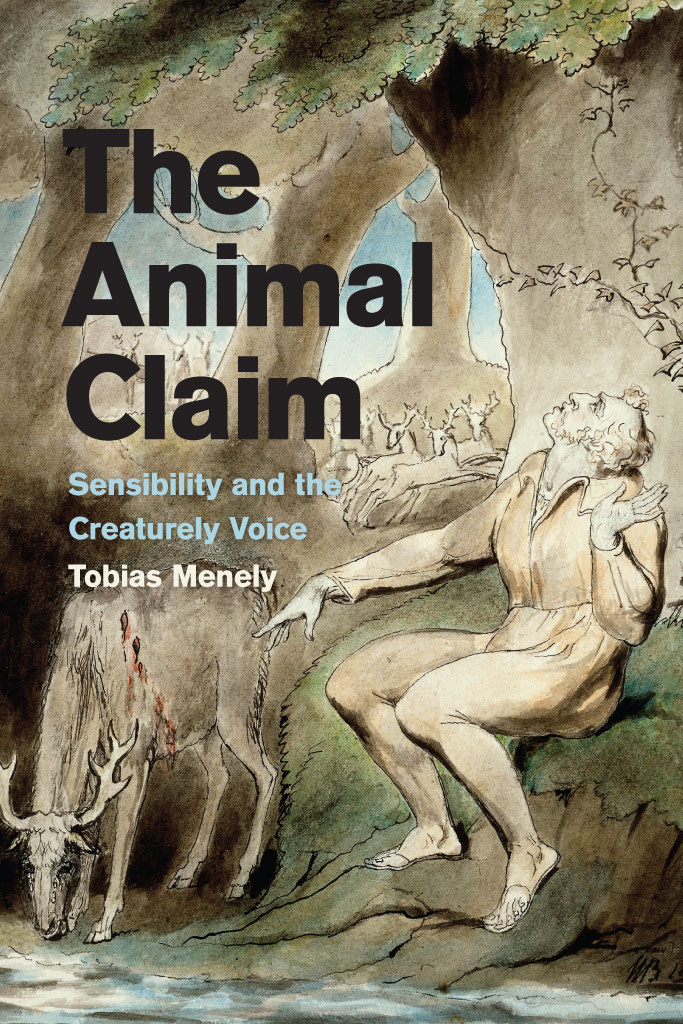

TOBIAS MENELY is assistant professor of English at the University of California, Davis.

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

Menely, Tobias, author.

The animal claim : sensibility and the creaturely voice / Tobias Menely.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

isbn 978-0-226-23925-5 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-226-23939-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-226-23942-2 (e-book) 1. Animal societies. 2. Animal behavior. 3. Human-animal relationships. 4. Animal psychology. 5. Hume, David, 17111776. 6. Enlightenment. I. Title.

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Cette rupture de lidentitcette mue de ltre en signification, eest--dire en substitutionest sa subjectivit du sujet ou sa sujtion toutsa susceptibilit, sa vulnrabilit, cest--dire sa sensibilit.

Emmanuel Levinas

Contents

This book considers the manner in which animal claims regarding injury or interest come to be acknowledged in a given community. A claim, etymologically, is an assertion of right, the medium of which is a calling out, a cry, or a clamor. We can detect a related association in the metonymy that links voice with a precarious form of social personhood, with a right asserted, if not fully recognized, to express an opinion or seek redress, to be heard or participate. Voice, in its primary usage, refers to the sound produced by the vocal organs in humans and other animals, but by the sixteenth century it had come to imply political communication as well, a medium of command and of protest. The Age of Sensibility supplies both my historical example and the terms of my analysis of the place of advocacy, the act of representing or speaking for another, in post-absolutist political community. As with claim, the etymology of advocacy hints at the problem of a nonsymbolic communicative injunction. From the Latin vocare (to call), which has as its root vocem (voice), an advocate is one called upon by anothers voice to speak for others in his or her own voice. To recover the force of the vocal imperativeits capacity to intervene or interpose, its availability to redirection or remediationis to understand community not as a closed system of reciprocal entitlements, but as something constitutively open to those whose voices lay claim to rights not yet recognized.

I characterize sensibility, first and foremost, as a semiology for which the communication of passion is understood to exemplify the mediational work of the sign. Writers in the long eighteenth century developed a novel conceptualization of the significance of vocal and bodily expressivity, the prelinguistic semiosis humans share with other animals. In Characteristics of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times (1711), Anthony Ashley Cooper, the sentimental moral philosopher and third earl of Shaftesbury, describes this form of communication, which he sees as the very wellspring of social life: It will be considered how many the pleasures are of sharing contentment and delight with others, of receiving it... from the very countenances, gestures, voices, and sounds, even of creatures foreign to our kind, whose signs of joy and contentment we can anyway discern. Our companionship with others largely transpires by way of this sign reading, this sympathya word, for Shaftesbury, synonymous with communication. Sympathy not only bridges the species divide, joining creatures in common felicity, but, in an even more forceful overcoming of identitys hold, it draws us from our contentment into a recognition of anothers suffering. In Enchiridion Ethicum (1666), the neo-Platonist Henry More, a vehement critic of the Cartesian bte-machine, described those efficacious sorts of Eloquence, [Nature] has bestowed on so many of the Creatures when they are oppressed, for the drawing of Compassion towards them. Such is the querulous and lamenting tone of the Voice, the dejection of the Eyes and Countenance, Groaning, Howling, Sighs, and Tears, and the like. For all these have the Power to incline the Mind to Compassion, whether it be to quicken our Help, or to retard the Mischiefs we intended. Shaftesbury and More presume that the inner lives of other creatures are discernible, that passions signify, and that this signification effects a transfer not of idea but of feeling. Shaftesbury regards sympathetic communication as the precultural origin of sociability, the natural condition of our historical socialization. More attributes to the creaturely voice a performative efficaciousnessa power comparable to the assimilative force of sympathy in its premodern, preternatural sensethat would transform our interests, aligning us with creatures who might otherwise serve our ends. Both of these early theorists of sensibility regard the impassioned voice, rather than the spoken or written word, to be the elemental medium of community.

Sensibility expands and revalues the domain of communication Aristotle had identified with the voice (phone), which, he writes in the Politics, is but an indication of pleasure and pain, and is therefore found in other animals (for their nature attains to the perception of pleasure and pain and the intimation of them to one another, and no further). In their accounts of sympathetic communication, Shaftesbury and More identify an oversight in this canonical definition of voice: other animals disclose their pleasures and pains not only to one another but to us as well. We recognize ourselves to be addressed by animal voices, to be the recipients of signs that solicit our attention. Before we enter into what is for Aristotle the properly political sphere facilitated by conventional, symbolic language, we already inhabit a world in which we are subject to the claims of other expressive creatures.

In this book, I argue for an understanding of sensibility, and particularly of the dynamics of sympathy, as oriented around questions of communicationrather than, say, cognition, phenomenology, or epistemology. What I find compelling about eighteenth-century sensibility, as a semiology, is not its systematicity, but its interest in the thorny problem of conceptualizing the relation of natural signs (such as countenances, gestures, voices, and sounds) to instituted signs (arbitrary, conventional, and symbolic) and other forms of media, or implement[s] of intercommunication, as Charles Sanders Peirce writes in his call for breadth in any account of sign relations. Writers of sensibility are concerned with the conveyance of passion as well as idea, with representation and reference but also with the manner in which signs remediate other signs, occur within and transform intersubjective relationships, unleash effects and instigate response. Consider the communicative exchanges described by Shaftesbury and More, the cascade of relational actions and perspectival shiftssharing, receiving, discerning, drawing, inclining, quickening, retardingprecipitated by the creatures signifying voice.