All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

INTRODUCTION

If, when I was a child, someone had told me, One day, youre going to open a small Basque restaurant, I wouldnt have been too surprised. In fact, I would have probably shrugged my shoulders and said, Yes, of course I am.

For as long as I can remember, I have wanted to open a restaurant. I grew up in Minnesota, but my parents emigrated from Argentina just before I was born, and my sisters and I were raised around a table with lively Spanish conversation and with food that was strange by midwestern standards (at the time, we may have been the only Argentine Jews in Minneapolis). Growing up, my favorite pastimes were playing restaurant, dreaming about food, and reading cookbooks, so opening a restaurant someday would not have seemed impossible.

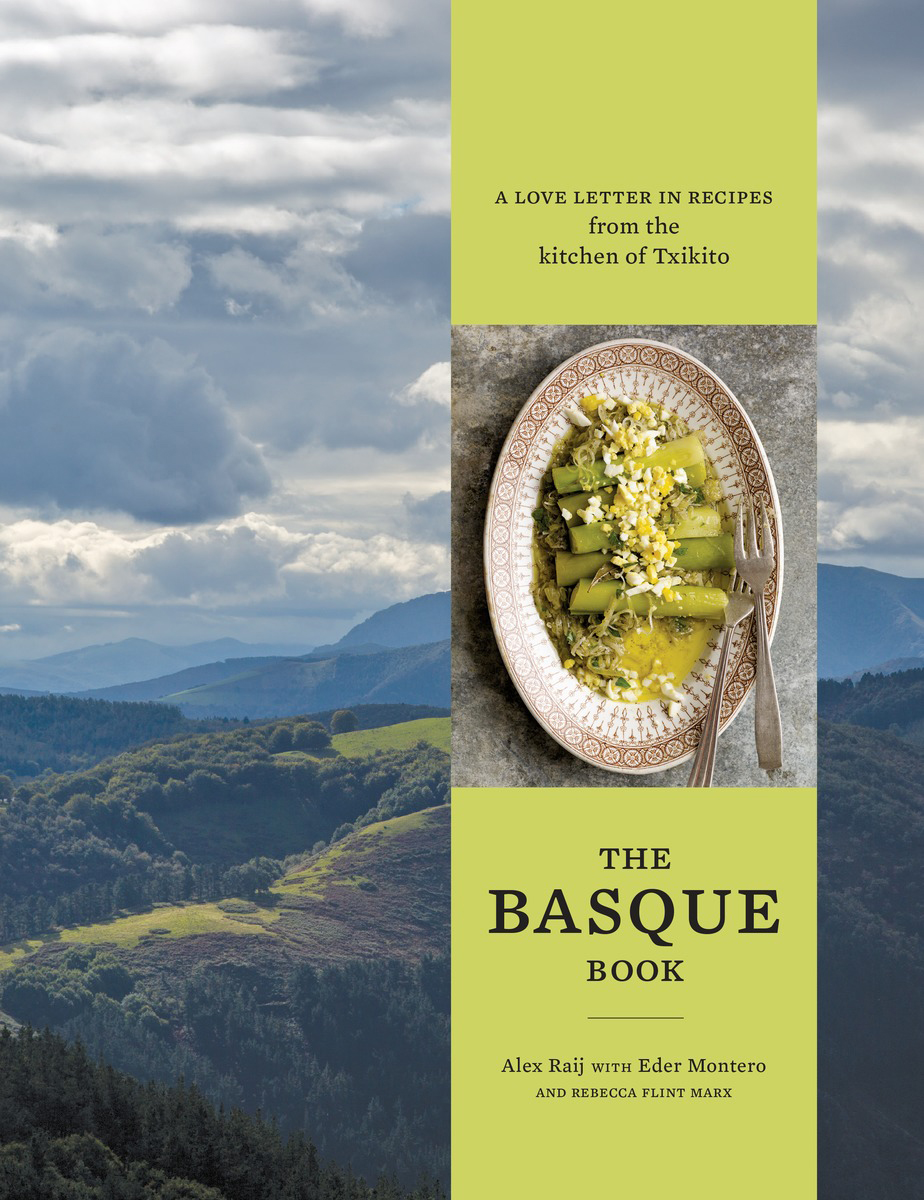

As fate would have it, I grew up and opened a small restaurant in one of the biggest cities in the world. But the part that would have surprised me as a childand, in a way, still surprises me todayis that my restaurant, Txikito, is Basque. I can imagine my ten-year-old self scratching her head and asking, What does Basque mean? Ive been running Txikito since 2007, and I still dont have a definitive response to that question. But its one that I strive to answer, for myself and for the people we feed, every day.

Cooking is a perfect vocation for people who like to find and make connections. To me, food is a way to tell a story, and even though I dont want to tell the same stories over and over again, I do want a common thread to connect the stories that I do tell. My husband, Eder, who is also my co-chef at Txikito, puts it a little differently: he says Id open a new restaurant every week if I could. So its not surprising that he is both frustrated by and supportive of this story, which is the story of how I met Basque food and found a home in a cuisine that has held my attention in ways that no other can.

Part of what made both Basque food and Eder, who is Basque, so attractive is that Basque cooking meant that I could return to living my life in Spanish. My affinity goes deeper than that, however: I love all of the cuisines of Spain, but Basque food has a very specific mystique. It doesnt hide behind strong Mediterranean flavors. Instead, it celebrates single ingredients and tastes and constantly reminds the cook that simple doesnt necessarily mean easy. Basque food makes you a better cook. It teaches you to respect ingredients, embracing and amplifying their natural flavors. Id argue that many professional cooks would get better if they practiced Basque cooking, as it forces you to unlearn bad habits and pay attention to details. The Basque cook responds to la materia prima, or main ingredients, a tiny bit differently each time. Intuitively understanding how to make these minor adjustments is a sign of the cooks experience and skill.

My Basque journey started well before I met Eder. In Minnesota, my dads best friend was nicknamed El Vasco, a terrific cook who made the most amazing homemade pizza and cherries jubilee, a dessert that turned my favorite fruit into a pyrotechnic miracle of flavors. El Vascos real name was Nestor Riviere. He was my dads tennis partner and a mathematician, and our families often cooked together. I had a girlish crush on Nestor: he drove a Fiat Spider and had salt-and-pepper hair, but in retrospect, what made him so seductive was how he cooked and what happened when he did. At home, cooking was always interesting, though a rather calm routine. El Vascos cooking was flamboyant and extroverted and was meant to make people fall in love with him. It was a flirtation more similar to the kind you find in restaurant cooking, where customers are seduced by a combination of flavors and spectacle.

Every year our families held a huge pig roast at a place in Minneapolis called Hidden Beach, on Cedar Lake. Those roasts were epic, all-day parties that began early in the morning and went late into the night and seemed to bring out every Spanish- and Italian-speaking expat from the University of Minnesota. The men, who were mostly math professors, would build the roasting pits out of cinder blocks and old fences or mattress coils and then spend the entire day feeding the fire, drinking cans of Special Export, and talking tennis while the pigs slowly cooked. It was the 1970s, and everyone was tennis obsessed. Guillermo Vilas, Bjorn Borg, Ivan Lendl, and Jimmy Connors were popular topics of conversation, and some of the guys would go off to play a match while the rest of us waited for the pigs to be ready. Someone was always strumming a guitar and singingagain, this was the 1970swhile the women gossiped, cooked sausages and offal, and reheated empanadas on foil rafts, and we kids ran around, free to do whatever we wanted. My sisters and I would fall asleep on the car ride home, smelling like smoke, our faces dirty with soot, and the shirts over our full bellies stained with grease.