All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisheror, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agencyis an infringement of the copyright law.

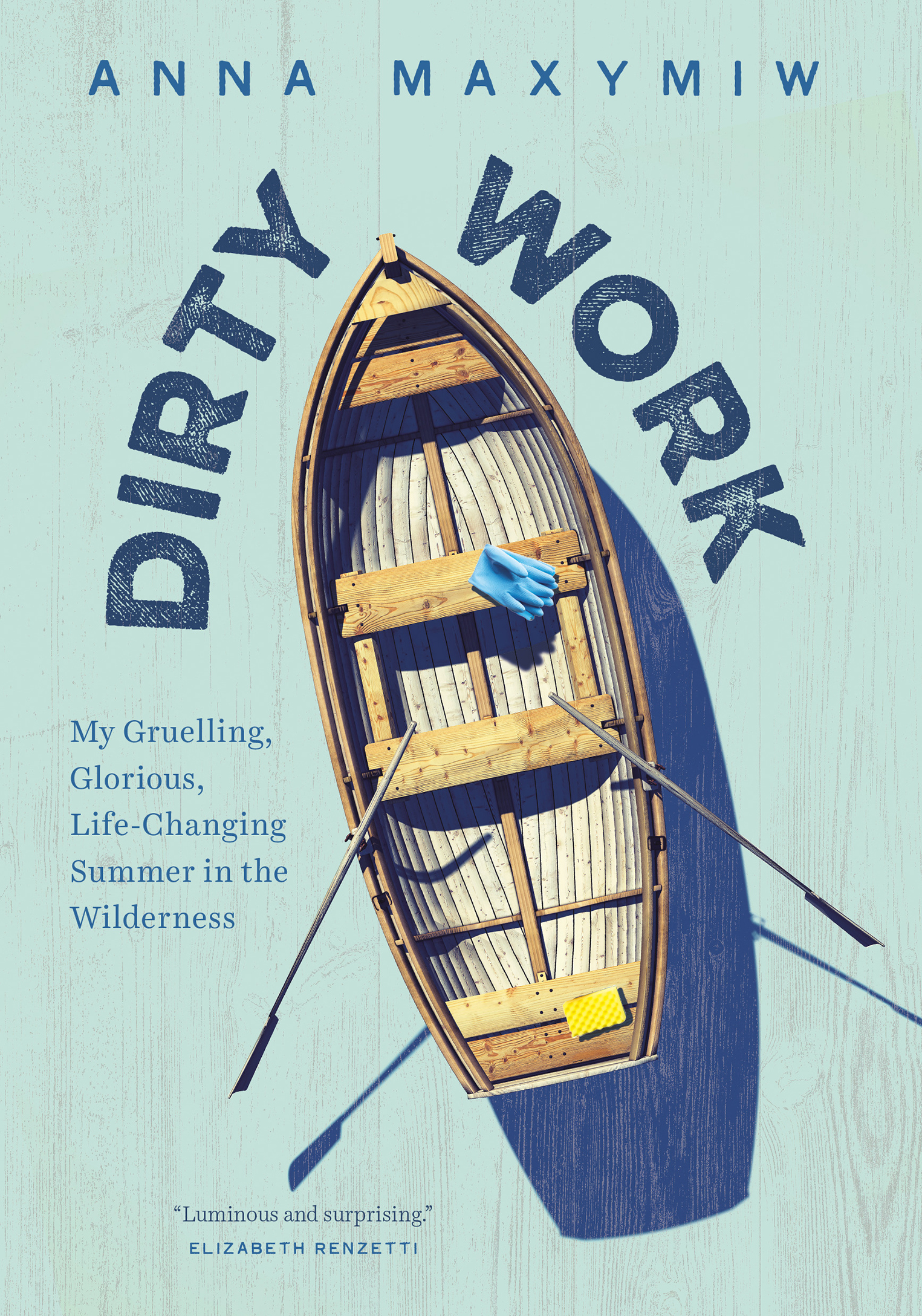

Dirty work : my gruelling, glorious, life-changing summer in the wilderness / Anna Maxymiw.

1. Maxymiw, Anna. 2. Fishing lodgesOntario. 3. Outdoor life. 4. Self-actualization (Psychology). 5. Authors, Canadian (English)21st centuryBiography. I. Title.

Cover art: boat Chris Clor/Tetra images/Getty Images cleaning supplies DragonImages/iStock/Getty Images

McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company

I think the land knows we are strangers.

THE LAND OF LITTLE STICKS

DHC-2 Beavers stopped being produced in 1967, you know, the pilot tells me with a shit-wild grin. I cant see his eyes behind his huge sunglasses, but I know that hes hungover from the way he speaks, and the way he slung himself into the front seat of the plane. By that logic, the de Havilland floatplane Im sitting in is just about fifty years old, and it looks itworn grey seats, ancient controls, a smeared windshield.

I clench at his words, regretting all the decisions I made that have led me to this point. Deciding to spend a summer in remote Northern Ontario was all well and good when I was in the city, but now that Im here, at the very moment were about to depart, I begin to panic. Nothing about thisthe pilot, the plane, my surroundingsis reassuring.

Some people might call it brave, the act of getting away and stepping so far out of ones comfort zone. But I dont feel brave. Instead, I feel my thighs start to sweat, my skin sticking to the plane seat and the skin of the two girls who are wedged in on either side of me. On my left is Sydney, to my right is Robin, and in the front seat, theres Connor. Im too wrapped up in a complicated web of nerves and regret and a strange form of excitement to feel brave. None of us speaks.

If you need to puke, the pilot continues, filling our silence, there are barf bags in the backs of the seats in front of you. When I reach into the pocket hes referring to, I pull out flimsy plastic shopping bags, which are full of holes.

Behind me, the plane reverberates with a dull thunk as a member of the air base staff throws my duffel bag into the boot and slams the door. My palms are damp and my mouth is dry; I try not to move my hands around too much, so the others wont notice that Im shaking. Its not too late, I tell myself, to get the hell out of here. Its not too late to unbuckle my seatbelt and wriggle out from between this sweaty female flesh, climb over hips and stomachs, and fling myself out of the plane and back onto dry land. I could tear my bag out of the back if I really wanted to; I could kick up a fuss. I could leave and spend my summer in a different place, a place where I wont run into black bears, where I wont have to spend nine weeks cleaning up after middle-aged men, where I can step outside and blackflies wont immediately gather on my eyebrows and temples like a bloodthirsty crown. That would be the easy choice. Because I know that nothing about where Im going will be easy. I know that because Ive been there once before, and Im scared to return in a different capacity, scared to revisit this place that has hung, wild and lush and gesturing, in my dreams for a year.

The propeller starts with a thunderous moan, and I jump. The sound fills the tiny plane body, all-consuming; it vibrates into my bones, all the way up to my teeth, like the purr of a huge, rusty cat finally getting attention; it crowds me so much that there isnt space for doubt. Theres only space for momentum, for self-preservation, so I yank the padded headset over my ears, double-check that my seatbelt is buckled, and curl my fingers under the lip of the seat. Theres nowhere to go but forward. Theres nothing to do but take off.

Three other planes have gone up before us, carrying cargo and the rest of my co-workers. We four are the last to be delivered of thirteen young adults from different towns all around the province, mostly strangers to one anotherall of us running on empty stomachs and a bad nights sleep at the air bases piece-of-shit bunkhouseabout to spend late May to late July working together at a fishing lodge in the Northern Ontario bush.

Northern Canada: The land of little sticks. Its a part of the country that evokes divisive emotions in those who have seen it or live on itor have tried to live on itand now its going to be my home for the summer. Ive done a little bit of reading on this place. I wanted to know what people had to say about it, bad or good, whether they were entranced or repulsed. The land that God gave to Cain, Jacques Cartier wrote when describing the northern forests of Quebec. I cant help but replay those words to myself as I think about the summer ahead. In fact, Northern Canada was deemed so worthless that, in 1670, Englands King Charles II gave the land away7.7 million square kilometres of itto the Hudsons Bay Company, which, it might be said, turned a good profit off of it. And so Northern Canada, this tangle of bog, fen, black spruce, and myth, is known as many things, depending on who you speak to: the nothing; the North; a wasteland; a dream destination; a place of infinite and strange beauty.

Our destination, Kesagami Wilderness Lodge, is in the Hudson Bay Lowlands, a geological region defined by peat bog and wide, slow-moving rivers, which sits about a hundred kilometres south of James Bay, near the Quebec border. You cant drive to where were going. The labyrinth of trees and water stops you in your tracks. Roads end as if youre about to drive off the Earth. So, we made our way by train through the Canadian Shield, that ancient plate of granite that grips half of our country, unforgiving rock that had to be blasted through to build roads and the railway. Were heading for the middle of Kesagami Provincial Park, to the eastern side of Kesagami Lakea big body of water, about 32 kilometres long and 12 kilometres at its widest, with about 290 kilometres of shoreline. Kesagami means big water in Cree, and the name is fitting. Big water, big land, big fish, big possibility.