Dedication

To my friend Debbie Gooch, who introduced me to Dean and Sel, invited me to join the dorm-room cooking club, took me along on my first trip to New York City, and brought me home to Reidsville for my first Brunswick stew. Thank you for stirring the pot and seasoning it just right, then and now.

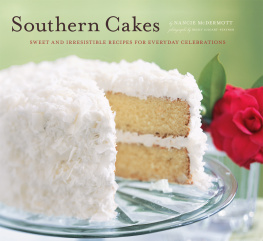

Text copyright 2015 by Nancie McDermott.

Photographs copyright 2015 by Leigh Beisch.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN 978-1-4521-2485-8 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-4521-3230-3 (epub, mobi)

Designed by Christy Sheppard Knell

Prop styling by Sara Slavin

Food styling by Daniel Becker

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Introduction

T hroughout the region we now call the American South, long before anyone put a sharpened feather to parchment paper and penned observations about it, nourishing soups and hearty stews were bubbling away on wood-fueled fires. In ceramic vessels, redware stewpots, three-legged pipkins, bulge pots, and enameled Dutch ovens, Southern cooks have been simmering and stirring for centuries, adjusting the heat of campfires, stoking the embers on open hearths, and feeding sticks into wood-burning cast-iron stoves. They were stewing and braising, winter and summer, long before the counties, towns, and states we now call home showed up on any map. Cherokee, Lumbee, Tuscarora, Seminole, and Choctaw people cooked fresh and dried beans, squash, hominy, and green corn. Newcomers from the British Isles, Europe, West Africa, and the Caribbean Islands cooked greens, field peas, potatoes, and pumpkins, stretching wild game, shellfish, and salted meats to satisfy an abundance of eaters around great tables. They paired their long-tended handiwork with corn cakes, grits, biscuits, and rice. As the nation grew, this process of invention and evolution grew right along with it, creating a culinary repertoire of soups and stews that continues to this day.

We dip our spoons into a Cajun-style gumbo; savor a layered muddle of snapper, potatoes, onions, and poached eggs; feast on okra soup colored with red-ripe tomatoes; eat hoppin John for luck on New Years Day. With each bite, each sip, each stir, we are tending a bed of gently glowing coalsembers from a fire lit long ago and nurtured over time by many hands. By keeping the stewpots of the historical Southern kitchen bubbling, we encourage remembrance and fuel creativity. We feed our spirits while planting seeds saved from long-ago harvests. Cooking and eating together helps us keep the old ways vibrant, and visible, where we can adapt them to suit what we have now; what we need and wantwhat we are hungry for today.

This book is a handbook, a workbook, and a playbook designed to help you celebrate the regions culinary traditions, the multiple and varied ways of working in the kitchens, gardens, farms, and wild spaces of the South. My goal is to feed your curiosityto spark your interest as well as your appetite for wonderful home cooking, plain and fancy. These recipes provide you with a sampler, an initial tour of the Southern culinary landscape, lifting up various ways we feed ourselves and our dear ones with big, bold, substantial, and satisfying servings of braises and broths, dumplings and gravies, bisques and boils, soups and stews.

But how to organize it, how to come at the oversize, multifaceted subject of Southern soups and stews in a way that clarifies it, increases understanding and knowledge, and sparks interest? Regional distinctions within Southern cooking have always fascinated me, so that is the first approach I considered. On this aspect of Southern cooking, they are abundant. There are so many distinctions within a region or subregion that such a focus creates confusion. Even within one region and one community within that region, variations bubble up to the top of the pot. Legendary chef Paul Prudhomme speaks fondly about growing up in the heart of Cajun country, the town of Opelousas, Louisiana, feasting on boudin, tasso, andouille sausage, and other forms of porky goodness. He looked forward to family expeditions to another heart of Cajun country, down on the bayous and along the Gulf Coast, where his equally Cajun cousins shared their corner of the countrys abundance of seafood: fresh shrimp, oysters, and a variety of fish. Even within the Cajun tradition, variations appear and absolutes dissolve like sugar in hot tea. Chef Pauls own family gumbos included both superbly fresh seafood from his bayou-based Cajun family members and hearty spice-infused sausages and meat from his own family of upcountry Cajuns. Surf and turf, powerfully seasoned and shared with pleasureall within one Cajun family.

What makes this gumbo Cajun, or that dish Creole? These are complex unresolved questions for which there are numerous answers and ideas, in regard to the term Creole in particular. People just do not agree, and after pondering and exploring the issue as I wrote this book, my conclusion is this: It does not matter. Rules about what goes into a Cajun gumbo or a Creole gumbo are easy to find if you go hunting for data; but not one of them held up. Particular people insist that this ingredient would never be in such-and-such a recipe, or that ingredient would always be in that one, and then here comes a fine version that breaks that rule. To me, it doesnt matter and wont be solved here. In this book, when I say its a Creole gumbo, its because the person whose gumbo it is or on which it is based is Creole. Same for Cajun. And that is good enough for me.

HOW ABOUT A HISTORICAL APPROACH? Theres a tempting one, given the span of four centuries during which the South has been home to bubbling pots of stew. A seasonal approach could work as well, arranging soup and stew recipes into a Southern cooks almanac. I could move from dried beans and salt pork in February to freshly picked English peas with silken dumplings in late spring; from okra soup with juicy tomatoes in August to massive pots of Brunswick stew and burgoo, cooked and stirred outdoors, come fall.

Or perhaps a cultural calendar, approaching the subject through signature soups and stews linked to celebrations and rituals. Creole cooks in New Orleans cook up gumbo zherbes on Holy Thursday, and families in the Piedmont of North Carolina, pry open oysters aplenty for the Christmas Eve tradition of oyster stew. Then we could go back to New Orleans for the Monday tradition of red beans and rice. Up until the mid-twentieth century, Mondays were washdays, and the demanding work of doing a households laundry by hand left cooks little time to prepare the evening meal. The solution was to put a big pot of red beans with sausage and spices on the stove as a back-burner supper. Creole red beans bubbled away all day, providing everyone with a satisfying and substantial supper at days end.

Then I saw the patterns on which I needed to organize the story. Theyre a combination of an ingredient-centered approach with a recipe- centered approach. For ingredients, crab and shrimp have their own chapter, as do fish and shellfish, general vegetables, and field peas and beans. For recipes, gumbos have their own chapter, as do dumpling-blessed soups and stews, and Brunswick stews and wild game. This gave me a path to follow, which I tested out on the two ocean and coastal chapters.

Next page