contents

In memory of my mum | 19482017

What do you think of when you think of time?

Time is yesterday. Time is tomorrow. Time is the split second that you own, right now. Now its gone.

We hold time like a child, as memories. The memory of a close friend, the touch of your mothers hand holding yours, the pencil lines on the kitchen wall showing how you grew. Time is learning to ride a bike and its the feeling you remember when you fall off.

Its the next harvest and the storm coming. Its your dreams, your opportunities, your children. Its wishing it never happens and hoping one day it will. It is regret, and in the same breath, forgiveness.

We rise and sleep with the patterns of time, everyone on this Earth is bound up in its cycle. We build our days around the light from the sun; its arc through the sky is our most ancient timepiece. Light has sculpted the arrangements of daily life since the very beginning. Our routines have been moulded by it and our world shaped by it.

Time is made up of circles. As the planet turns we scratch marks on a calendar. These marks give us our months, as well as our four seasons: spring, summer, autumn and winter. Our months and our seasons make up our years.

We spend these years together with our families and our friends in our homes, where we build a world around us we can call our own. Our home is our centre, our core. Its the bridge from where we run things; its where we pilot our days and ride out our nights.

I can remember all the houses I lived in as a child. I have snapshots in my mind of everything from the light in the morning to the people in the kitchen. These houses often find their way into my dreams at night, beckoning me back into certain rooms, so I never forget their details.

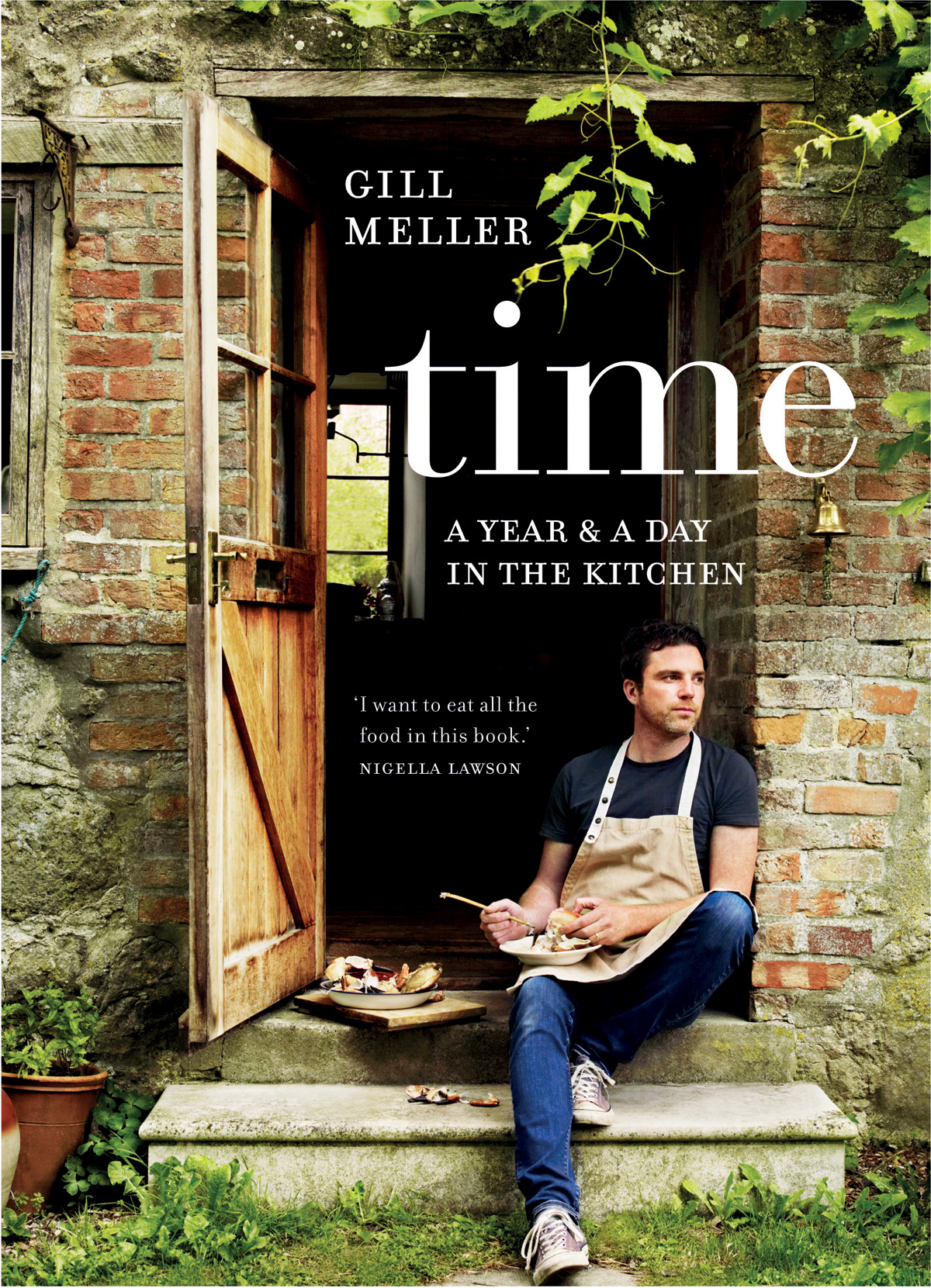

In my earliest years we lived in a beautiful house in a small village in Dorset. It was called The Old Parsonage and had a thatched roof and flagstone floors. The simple conservatory on the east gable was filled with a winding grapevine that would fruit in the summer. The kitchen was cool and bright with windows looking south towards the church and north towards the garden. When my mum washed up or prepared vegetables, she looked out over the beech tree with the swing we all loved, the garden and the vegetable patch. On one side of the kitchen was an old oil-fired Aga and on the other, a pine dresser that my uncle had made. In the middle of the room was a big wooden kitchen table. It was my mum and dads first home together but, more importantly for me, it was their first kitchen together, and it was in the kitchen that nearly everything of meaning seemed to happen.

We were just babies in that kitchen. Its where we met our mum and her mum. Its where we sat in our high chairs and saw her cooking throughout the day. We learned to eat around that table, we cried at that table, fought at it, slept at it, woke at it, and we learned to laugh together around it. It was at that kitchen table that plans were made for passages, and courses were plotted. It was the table where poems and plays were written and where people would quietly read, talk or listen. Its where they all poured wine, smoked, and sang a thousand songs. Its where we painted pictures, spilled our drinks and ate Mums spaghetti.

One of my earliest memories is of my dad picking freshly cooked crab at the kitchen table. He laid out sheets of newspaper first, and then used a smart-looking hammer with a stainless-steel top and light wooden handle to crack the shells of the crabs so that he could carefully remove the meat from inside. He worked through the claws first, which I found captivating, and then he would turn his attention to the main body, where the brown meat could be found. I now know, those big crabs were probably the same age as my dad.

During those early years we moved house several times, but in each successive home I remember the kitchen with the same affection as the first.

Our table and dresser always fell into place, bringing the room alive. The kitchen remained our sitting room, office, playroom, library and dining room all in one.

As I grew up in those kitchens, I gradually became immersed in food and cooking. I learned about the power of English mustard, and that lighters explode if you leave them by a cooker. I learned that Opinel knives are really, really sharp and how to swear quite well. My dad taught me that bacon and garlic belong together; my mum taught me how to eat mussels that had been cooked with shallots, white wine and flat-leaf parsley, and that perfectly scrambled eggs on toast can make almost anyone feel better. I learned to love the family salad dressing recipe as well as creamed spinach or anything in a well-made white sauce. I discovered that it was salt and pepper that made my parents supper taste so much better than ours, and my brother discovered, while standing on the table, that wearing Superman pants and a cape doesnt actually mean you can fly.

One house we lived in was next to an old sheep farm; we spent summers building dens in the hay barn, and then smashing them up. We would explore new ways to use nettles as weapons and plot how to lasso sheep so they could pull us along on our bikes. The kitchen had a big larder, with wooden shelves stacked with jars of fruit jam, pickles, cereals, and tins. There were paper sacks of muddy potatoes and firm white onions on the cool floor. I must have stood in there for hours thinking about what I could eat. My dad dug over an area of the garden for his vegetable patch; he would bring in leeks, runner beans, lettuce and rose-coloured raspberries he picked from the unnetted fruit cage. At the weekends the house was usually full, and the kitchen sang with life and cooking. We had great big fry-ups in the morning or Mums home-grown tomatoes, simply roasted with salt and marjoram and served on toast. Occasionally wed have a kedgeree, made with delicate haddock from the local smokery, soft-boiled eggs and fresh coriander, Then, of course, lunch, which could easily lead into supper.

On Sundays there was roast leg of lamb with peas and mint, and potatoes cooked in fat, a little garlic and rosemary.

When my mum went back to work, my dad had to learn how to make simple suppers that he could prepare for us after school. Some became legendary; some, not so much, but his cooking came from the heart. Dads leek and potato soup, for example, was a winter staple (theres a version of it ). And his liver and bacon with sage and his buttery mash were quite literally the best.

His legacy, however and his own creation will be spaghetti with bacon, garlic, Parmesan, olive oil and . He began by sizzling streaky bacon in a large frying pan with plenty of garlic. Once the spaghetti was cooked, it went into the frying pan, too. Then, he added the grated Parmesan by the handful and (heres the secret) he would fry the Parmesan with the spaghetti until it began to crisp on the base of the pan. Then, hed use a wooden spatula to scrape and scratch at the crunchy and, in some areas, chewy cheese, and thats when the freshly ground black pepper would go in.

![Nigel Slater - A Cooks Book: The Essential Nigel Slater [A Cookbook]](/uploads/posts/book/441033/thumbs/nigel-slater-a-cook-s-book-the-essential-nigel.jpg)