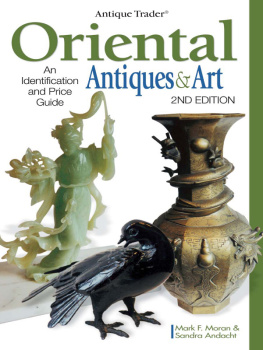

Antique Trader

Oriental

Antiques & Art

An

Identification

and Value

Guide

| edited by |

| 2ND EDITION | Mark F. Moran |

2003 by Krause Publications

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a critical article or review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper, or electronically transmitted on radio or television.

Published by

700 East State Street Iola, WI 54990-0001

715-445-2214 888-457-2873

www.krause.com

Please call or write for our free catalog of publications. Our toll-free number to place an order or obtain a free catalog is 800-258-0929 or please use our regular business telephone 715-445-2214.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2003107995

ISBN: 0-87349-698-1

eISBN: 978-1-44022-509-3

Printed in United States

Acknowledgments

Articles

Some of the articles contained in this volume have been reprinted with permission from the Orientalia journal.

Line Art (including Marks)

Carl Andacht

Photography

Mark Moran, Daniel Stone Studios, Floral Park, New York, and Tom Edson (photographs of the Edson and Luhn collections)

A special thanks to the following for their contributions and support: Leon and Toni Andors, Richard A. Bowser, Lee Chinalai, Leonard Davenport, Tom and Kay Edson, Arthur Field, Liz Fletcher, Mark Fogel, Paul Fogelberg, Richard and Karen Goodman, Harold Jaffe, Howard and Florence Kastriner, Charles Kelly, Virginia Keresey, Larry Kiss, Dr. Michael B. Krassner, Richard Lambert, Steve Leonard, Ina Levy, David Migden, Carol Mohlenhoff, Raymond Nickel, Gardner Pond, Dr. and Mrs. Bernard Rosett, Mrs. Florence Simon, and Dr. and Mrs. Sam Sokolov.

The authors appreciation is also expressed to the press and Oriental departments of Christies and Christies East, New York City.

Contents

Introduction

Art and antiques from China, Japan, Korea, the Pacific Rim, and Southeast Asia have fascinated collectors for centuries. The study of treasures from even one of these areas has been a lifes work for many devotees, but for the beginning collector, the main obstacle has always been the language.

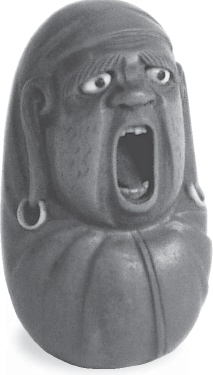

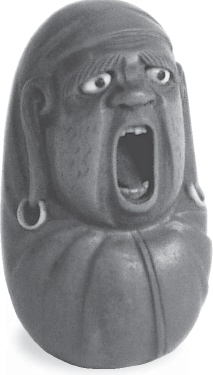

Who are the Ainu? What is the origin of Banko pottery? How was a cha wan used? Why is the figure of Daruma so distinctive? How long did the Edo Period last? Are Guan Yin and Kuan Yin the same? What is the chief attribute of Jurojin? Would you want to drink from a kapala? Is the Manchu Dynasty known by other names? How did Mu Wang often travel? Should you be afraid of an oni? Whats another name for paulownia? How did Rimpa painting get its name? What is the composition of sentoku? When did Tien Chi rule China? How is an uchiwa different from other fans? Where was a yatate usually attached? When was Zeshin active?

The answers to all these questions may be found in the 4,000-word glossary that has been exhaustively researched to take some of the mystery out of collecting antiques and art from the Far East.

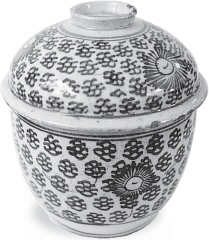

For instance, heres part of a sample description you might find in an antique shop, reference book, auction list, or price guide:

Document box and cover, gold hiramakie, nashiji, takamakie, and hirame on roironuri ground with pine, grasses, and flowers in a continuous pattern

Pretty confusing for the beginner, isnt it?

Heres what the detailed listings and glossary in Antique Traders Far EastAntiques & Art will tell you:

Document box (called a bunko in Japan) and cover, gold hiramakie (a Japanese lacquer technique, known as low relief, this technique was introduced in the Kamakura period [sources differ: either 1186 or 1192 to 1333]; a single layer of lacquer is applied to the ground, sprinkled with gold or silver powders, and allowed to dry; a coat of thin lacquer is then applied to fix the particles, and given a final polish), nashiji (irregularly shaped flakes of gold suspended in clear or yellowish lacquer; also called pear ground, gold, silver, or gold-silver alloys of reddish-yellow coloration used on lacquer, principally as a ground), takamakie (high relief; this technique involves building up a design using two or more layers of lacquer or lacquer compounds; the final surface is usually decorated), and hirame (large, irregular flakes of gold roughly sprinkled on a black lacquer ground, also fat gold flakes used in lacquer decoration, named for their resemblance to a flounder) on roironuri ground (a waxy black or mirror-black finish; a brilliant and highly reflective black lacquer) with pine, grasses, and flowers in a continuous pattern

And thats just a tiny fraction of what youll find. By tapping this wealth of information provided in Antique Traders Far East Antiques & Art, the better equipped youll be to start acquiring treasures of your own.

The gathering of information for this book was greatly assisted by appraiser James E. Billings of Minneapolis, who also served as a consulting editor; Richard K. Spence of Circle of the Moon Antiques in Cherry Hill, New Jersey; and Edgar L. Owen, Ltd. of Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey. Detailed contact information for each of these can be found in our Resources section.

Apparel and Textiles

CHINESE APPAREL

Early Chinese apparel was characterized by upturned slippers, flowing robes, full sleeves, unshaped shoulders, and a center front opening. With the beginning of the Manchu Dynasty, many fashion changes took effect: The shaved head and queue (long, hanging braid worn at the back of the head) replaced the Chinese topknot, for instance. The Manchu also redefined the style of clothing worn by both government and court officials, introducing slim belted trousers, boots, tight sleeves, close-fitting bodices (which overlapped on the front from left to right), horseshoe cuffs, and slits in the robes. The dragon robe, a semiformal court coat, was reserved for members of the Imperial family and for other nobles and officials. The five-clawed dragon was worn exclusively by the Emperor and his family.

In the mid-17th century, the Manchu rulers adopted the use of mandarin squares, badges worn to indicate rank. Civil officials wore various bird insignia, and animal insignia designated military officials (see accompanying table). A solid square was used for the back of an outer jacket, and a split square (two halves) was worn across the open front. The badges were appliqued in place and could be easily removed or changed as the wearers rank was upgraded.

Next page