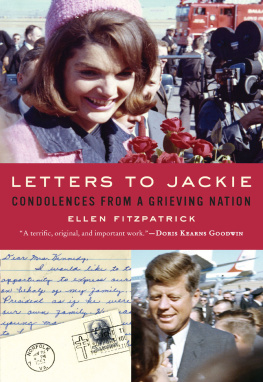

DEAR MRS. KENNEDY

Also by Jay Mulvaney

Essentially Lilly

Diana and Jackie

Kennedy Weddings

Jackie: The Clothes of Camelot

JAY MULVANEY AND PAUL DE ANGELIS

Dear Mrs. Kennedy

A WORLD SHARES ITS GRIEF

Letters, November 1963

ST. MARTINS PRESS

NEW YORK

DEAR MRS. KENNEDY. Copyright 2010 by Jay Mulvaney and Paul De Angelis. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address St. Martins Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.stmartins.com

See .

ISBN 978-0-312-38615-3

First Edition: October 2010

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

In the weeks and months following the assassination of her husband, Jacqueline Kennedy received nearly one million letters. They came from every state in the nation, from every corner of the globe. The impact of President Kennedys death, coupled with Jacqueline Kennedys magnificent deportment throughout four terrible days in American history, was so immense that people from all walks of life wrote to a woman almost none of them knew.

These letters, which Jacqueline Kennedy pledged would be on display at the Kennedy Library for you and your children to see, have, in fact, been tucked away in the librarys archives, largely unnoticed for over forty years. Filled with emotion, patriotic sentiment, and insight, they are a poignant time capsule of one of the seminal events of the twentieth century.

Few single moments in modern history have riveted the world in the same way as JFKs killingthe 9/11 tragedy is perhaps the only other recent one. After the assassination, however, the collective grief of millions focused on a single person. From Fifth Avenue and farmhouses, from palaces and prisons, from classrooms and communes, people wrote to Jacqueline Kennedy in the fall and winter of 196364. For some it was a formality, a diplomatically prescribed response to the death of a world leader. For friends and relatives, it was the heart-wrenching desire to offer some small dose of consolation. But for hundreds of thousands of others, those with no connection to the Kennedys beyond a voting booth, a viewing of Jackies televised tour of the White House, or a photograph in a newspaper, some inner force compelled them to pick up their pens and write about how the death of John F. Kennedy affected them.

Many factors gave rise to this unprecedented display of communal sympathy. To people in America, and throughout the world, John F. Kennedy represented hope for the future. His initiatives, among them his promise to land a man on the moon, captured the imagination and the spirit of the times. His famous call for serviceAsk not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your countryinspired Americans of all ages, urging dedication to some larger purpose. When people looked at JFK, many saw in him their better selves.

Also, the barbaric nature of John Kennedys death was truly shocking. It was unthinkable that the President of the United States could be shot dead in the streets of an American city. And yet it happened, in plain sight, at half past high noon.

Then, throughout the days that followed the assassination, Jacqueline Kennedy held the focus of the world. Her unwavering composure enabled Americans to start to piece together their own shattered national confidence. An insightful British journalist wrote: She gave America the one thing it has always lacked and this is majesty.

Finally, the assassination, and its aftermath, was the first national tragedy to play out during the era of modern mass communication. For the first time in history, television news coverage continued nonstop, for four days straight, with no commercial interruption. Due to the advent of satellite technology, people across the country and around the globe were able to watch events unfold before their eyesthe eulogies and orations in the Capitol Rotunda, the killing of Lee Harvey Oswald, the walk behind the caisson to St. Matthews Cathedral, John Kennedy Jr.s salute to his dead father. These images were further seared into our national psyche by influential picture magazines of the day like Life and Look and later magnified by the work of pop artists like Andy Warhol. Over time they became the defining imagery of a generation.

The letters came addressed to Mrs. John F. Kennedy, The White House, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C.; they came addressed to Madame Kennedy, Washington; to Mrs. President, America. For weeks they arrived at a rate of thirty or forty thousand letters a day. People wrote to a woman whose bravery and grace inspired them. They wrote to share their thoughts and feelings about the President whom they loved and admired and emulated. They wrote simply as an outlet for their energy. The newscaster David Brinkley expressed it this way the year after Kennedys death: The events of those days dont fit, you cant place them anywhere, they dont go in the intellectual luggage of our time. It was too big, too sudden, too overwhelming, and it meant too much. It has to be separate and apart. So people wrote to make sense of something that made no sense. Together, the letters form an immense chorus: a hymn of homage, longing, and grief.

Mail was coming in and it was being piled in the corridors... stacked in enormous cardboard cartons, one on top of another, from the floor to the ceiling, noted Jacquelines press secretary, Pamela Turnure, in the oral history she and social secretary Nancy Tuckerman recorded for the Kennedy Library. The deluge began on the Monday of the funeral, when all the letters that had been written on Friday and Saturday began to pour in from closer towns and cities. In those first days, Tuckerman recalled in 2009, neither the Pentagon nor the Justice Department was sure whether there was a wider plot. Security officials were eager for the First Ladys staff to keep up with the flow in case some letter offered clues to the mystery behind the shooting. In addition to the cards, telegrams, and letters were hundreds of packages. Once when Tuckerman entered the room where volunteers were opening up cartons containing gifts she heard a ticking sound in a box. A surge of alarm spread through the room... until it was discovered that the ticker was a mechanical toy truck from Germany meant for John Jr. that had been jostled and started up on its own. Besides toys, religious curios, flowers, and plants, came works of remarkable craftsmanship from all over the world: there were baskets and quilts of all kinds; a candle producer in Wiesbaden, Germany, sent an elaborate Kyrie-Candle complete with altar, robe, and crown.

After a week or two, the mail was diverted to the Old Executive Office Building next to the White House. Here offices were set up to handle the transition between administrations, and here Turnure and Tuckerman hoped to finally have enough room to sort and process the extraordinary volume of correspondence. Alas, the delivery crew got there first; Turnure wanted to burst into tears when she realized that the whole interior of what she had hoped would be a pristine new supply room was stacked from the floor to the ceiling with mail.

The overwhelming majority of letters were handled by a dedicated group of friends and volunteers who opened each envelope, carefully noting the names and addresses on multiple lists. Often personally moved, they pulled aside those letters they found especially touching, but soon these files grew to the thickness of the New York telephone directory. Boxes were set up on long tables to handle specific kinds of mail like Catholic Mass cards and contributions, suggestions for memorials, requests for photos, or for the funeral Mass card designed by Jacqueline Kennedy for the Presidents obsequies. Correspondence from friends and leaders was supposed to be culled from the torrent of mail, marked VIP, gathered in folders, and sent to Jacqueline Kennedy in Georgetown, where she had taken temporary refuge in a borrowed house. Because of the volume of mail and the tendency to use personal rather than official stationery, the importance of individual letter signers was far from obvious. Intimate friends who wrote personal messages were often even harder to recognize. Some people would catch on right away, some didnt, noted Nancy Tuckerman in the 2009 interview. Efficiency experts from Boston brought in to consult were amazed at the undertaking but could suggest no improvements. They thought we were doing the only thing we could do; to open them and see what they said, says Tuckerman.