C ONTENTS

A n enormous country, with a large population to feed and a diverse geography and climate, China has one of the great cuisines of the world and eating plays a major role in daily life and in rituals and festivities.

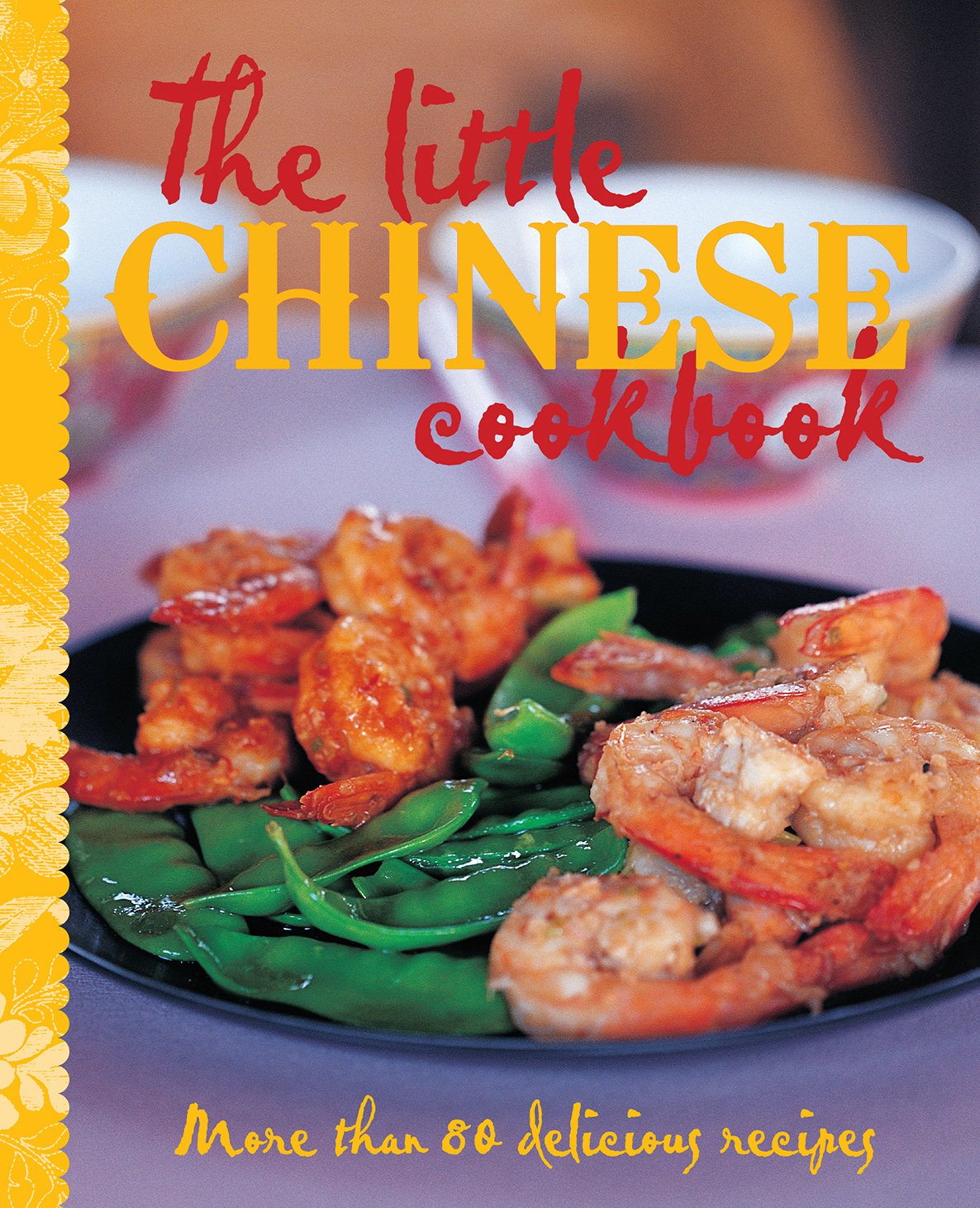

Chinese meals always have as their basis a staple, or fan, such as rice, wheat, maize or millet. Rice, always white and polished, is the food most associated with China and is usually steamed, while wheat grows well in the harsh climate of the North and is made into breads and noodles. In poorer areas, millet is more common, eaten as porridge. The staple is then accompanied by secondary dishes, or cai, of meat, seafood or vegetables, pickles and condiments. Snacks, from dumplings to spicy bowls of noodles, are eaten all day long, both as sustenance and to satisfy the taste buds.

INGREDIENTS

The most important factor is freshness: poultry and seafood are bought live, and a cook may make more than one trip to the market a day. Chinese cuisine developed around the foods availableoften there was little meat, poultry or fish, so rice and vegetables are particularly important. However, many of the foods we associate with China today, such as chillies, capsicums (peppers) and corn, all came to China via trading routes. The Chinese also incorporate a lot of preserved vegetables and dried foods, particularly seafood, into their diet, which is especially important in areas where the climate and terrain make growing enough food a struggle.

FLAVOURS

Chinese cooking tries to reach a balance between tastes: sweet and sour, hot and cold, plain and spicy. At the heart of Chinese food is a trinity of flavours: ginger, spring onions (scallions) and garlic. Although these are not included in all Chinese dishes, they do contribute to a flavour that is seen as being quintessentially Chinese. Soya bean products are another essential ingredient, and fermented tofu, soy sauce and bean sauces are tastes that define Chinese food, along with vinegars and sesame oil. In the West of the country, chilli and Sichuan pepper add heat to ingredients that are usually more simply cooked.

COOKING STYLES

A wok is without doubt the central item in a Chinese kitchen, and wok cooking, either stir-frying or deep-frying, is at the heart of Chinas quick style of cooking. Other techniques, such as steaming, poaching and braising, cook food more slowly. Few families own an oven, and foods that need to be oven-roasted, such as roast ducks or char siu, are instead bought from special restaurants. All food is prepared in China, where salads and raw foods are not eaten, and ingredients are cooked, however briefly, or preserved. A good Chinese meal will include a mix of cooking styles so all the dishes can be ready at the same time.

EATING

A Chinese meal will also consist of a number of dishes, all made to share, that are fully prepared in the kitchen (not even carving is done at the table) and can be picked up and eaten with chopsticks. All the ingredients must be fresh and the finished food served immediately. Stir-fried dishes should still have wok hei or the breath of the wok about them, indicating they have been cooked at exactly the right heat with exactly the right timing and have been served at once.

BANQUET FOOD

Food eaten at banquets is created to be the very opposite of the everyday diet of grains. The point of a banquet is eating for pleasure, not sustenance, therefore rice or noodles are served only at the end, and may be left untouched. Banquet food is often symbolic and as extravagant as can be afforded with dishes such as abalone, sharks fin and whole fish.

MEDICAL

In no other cuisine is the medicinal nature of food so tied to everyday cooking. Achieving balance at every meal is an essential part of Chinese cooking. Every ingredient is accorded a naturehot, warm, cool and neutraland a flavoursweet, sour, bitter, salty and pungentand these are matched to a persons imbalances: a cooling food for a fever, warming food after childbirth. As well as the use of everyday ingredients, there is the custom of using exotic foods, such as dried lizards, wolf berries and black silky chickens, often cooked in special soups and preparations.

THE FOOD OF THE NORTH

The cuisine of the North, with Beijing at its centre, comes from an area that is generally inhospitable with, apart from Shandong, little fertile land, harsh long winters and short scorching summers. Historically, the region has swung between drought and flooding from the Yellow River, Chinas Sorrow, though dams and irrigation schemes have improved things in recent years. The main crops have therefore always been hardy ones: wheat and millet are eaten as noodles, breads and porridge, while in the winter, vegetables such as turnips and cabbage are supplied to the capital by farmers from neighbouring provinces, who drive in trucks to Beijings markets and live on them until their load of vegetables has been sold. Shandong, on the coast, is the most fertile area and it has become a market garden of fruit and vegetables for the capital, as well as providing plentiful seafood.

Flavours are strong, with salty bean pastes and soy sauces, vinegar, spring onions (scallions) and garlic all being important ingredients. Winter vegetables are preserved or pickled, while spicy or piquant condiments are eaten with bowls of steaming noodles or rice when little else is available.

The main outside influence on the region has been the Muslim cooking of the Mongol and Manchu invaders who crossed the Great Wall from the North. Mutton and, in spring and summer, lamb, is sold as barbecued skewers on the street and stir-fried and wrapped in wheat pancakes. Steaming Mongolian hotpots and Mongolian barbecues cooked on a grill are seen everywhere.

Peking Duck, however, remains Beijings most famous dish, and is cooked in specialist restaurants all over the city. Beggars chicken is another local speciality, wrapped in lotus leaves and clay and baked for hours in hot ashes.

In stark contrast to the warming dumplings and hotpots of Beijings streets is the imperial cuisine created inside the Forbidden City. The presence of the court not only encouraged a huge diversity of cooking styles in the city from every province in China, but also elevated cooking to a standard probably never seen elsewhere in the world. Food was as important to the myth surrounding the Emperor as his armies, and he employed hundreds if not thousands in his kitchens. This elaborate cuisine is no longer reproduced in its entirety, but is remembered as a set of skills, recipes and flavour combinations important today in both banquet and everyday cooking.