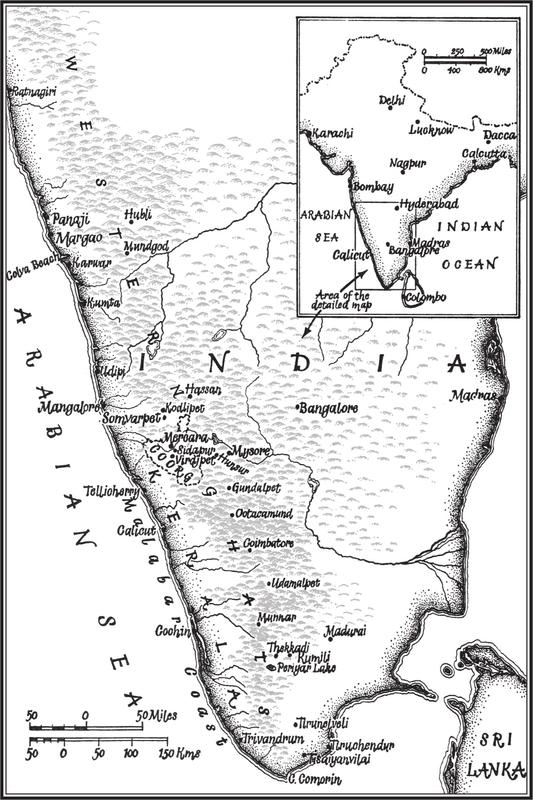

My thanks must go in many directions: to A. C. Thimmiah and Dr Chengappa of Virajpet, who made it possible for us to settle in Coorg; to the Bernstorffs of New Ross, who had us to stay for three months while I was writing this book and created a perfect background atmosphere of sympathetic encouragement; to Alison Mills and Karen Davenport who gallantly typed from an almost illegible manuscript without error or complaint; to Diana Murray who tactfully but relentlessly de-purpled many passages, and provided endless inspiration and comfort during the darkest hours of Revision; to Jane Boulenger and John Gibbins who helped prepare a chaotic typescript for the printer; to Patsy Truell who helped with the index and with correcting the proofs and to the editors of BlackwoodsMagazine and The Irish Times in which some extracts first appeared.

I n August 1973 it was exactly five years since I had been outside Europe. Therefore feet and pen were equally itchy and I decided that this was the moment before schooling started in earnest to share with my daughter Rachel the stimulation of a non-European journey. Already she had twice proved, on European testing-grounds, that she could enjoy short bouts of travelling rough: but I did realise that no five-year-old could be expected to proceed as speedily as my faithful bicycle or as sturdily as my Ethiopian mule.

A period of happy dithering followed; I consulted the atlas almost hourly and received much conflicting advice. One friend, a political journalist, thought International Harmony badly needed a book on China by D. M. and urged me to write to the Chinese Embassy in London. I obeyed, ingratiatingly quoting a pro-Mao passage from my book on Nepal, but there was no reply. From Australia, another friend who works in god-forsaken mines wrote that the outback has much more to it than Europeans imagine; that the animal life and landscapes are fantastic; that if I avoided all cities I would adore the place and could write a pornographic classic about the mining subculture. From Kuala Lumpur, a friends daughter who had been teaching in Malaysia for two years almost succeeded in persuading me that it is the only country worth an intelligent persons attention; and another friend was adamant that anybody who has neglected to walk through the Pindus Mountains knows nothing of the more sublime joys of travel.

Most tempting of all, however, were the letters from a charmingly eccentric millionaire who repeatedly invited us out to explore the mountains of Central Mexico. His Mexican estate is embedded in primeval jungle and the nearest town of any size is many miles away. I liked the sound of all this, and one does not have to be a nasty calculating bitch to appreciate the advantages of a tame millionaire in the background.

Meanwhile, my publisher (who is Rachels godfather and takes his duties seriously) was expressing the opinion that for me there is a book in Scotland. And left to myself I rather fancied Madagascar or New Guinea though neither, I realised, is the ideal country in which to blood a five-year-old.

In the end I settled for Mexico, under the influence of the superb photographs that arrived in the post at least once a month. Included were views of a Gothic-style temple recently built in the middle of a mountain torrent for a colony of tame ducks who had found the surrounding terrain uncomfortable. One day I showed these pictures to an imaginative friend who said, If thats what hes built for his ducks, what will he build for you?

Everybody was suitably impressed/censorious/envious/incredulous when I announced that soon I was going to Mexico to live with a millionaire in a jungle. But then a friend came to stay, who had just returned from India, and as we talked a most delightful feeling took possession of me.

I recognised it at once, though some years had passed since I last felt it. It was an excitement amounting almost to intoxication, a surging impatience that quickened the pulse. It was a delicious restlessness, a stirring of the imagination, a longing of the heart, a thirst of the spirit. It meant that I did not want to go to Thailand, Greece, Kenya, Australia, Malaysia, Dhagestan, Tanzania, Scotland, Madagascar, New Guinea, Mexico or anywhere other than India. It was absurd and, at that stage of my planning, downright inconvenient. But I welcomed it.

My choice of Mexico had been quite arbitrary. All the other possibilities had seemed equally attractive and just as likely to bear readable fruit; and this detachment had been, I now realised, a bad omen. If travel is to be more than a relaxing break, or a fascinating job, the travellers interest, enthusiasm and curiosity must be reinforced by an emotional conviction that at present there is only one place worth visiting.

Initially I felt bewildered by this effervescence of what must have been fermenting for years in hidden corners of my mind. Far from having fallen in love with India during previous visits I had been repelled by some aspects of Hindu life, irritated by others, uneasily baffled by most and consciously attracted by very few. On balance I had found the Indians less easy to get on with than the Pakistanis and Nepalese to say nothing of the Afghans and Tibetans and by making this fact too plain in my first book I had deeply offended a number of people.

Why, then, my compulsion to go back? I had no quasi-mystical ambition to improve my soul by contact with Hindu spirituality, nor had I forgotten the grim details of everyday Indian life the dehumanising poverty, the often deliberately maimed beggars, the prevaricating petty officials, the heat, the flies, the dust, the stinks, the pilfering. Is it, perhaps, that at a certain level we are more attracted by complexities and evasions, secrets and subtleties, enigmas and paradoxes, unpredictability and apparent chaos, than by simplicity, straightforwardness, dependability and apparent order? It may be that in the former qualities we intuitively recognise reality, and in the latter that degree of artificiality which is essential for the smooth running of a rationalistic, materialistic society.

Certainly I had always been aware without always being prepared to admit it that my more unsympathetic responses to Hindu culture exposed a personal limitation rather than the defects of Indian civilisation. In other words, India represented a challenge that I, like countless other Europeans, had run away from. However, unlike the impregnably self-assured Victorian imperialists I could not convince myself that a failure to appreciate India was a mark of virtue. So perhaps it is not really surprising that as the time-gap widened between India and me the pull to return to the scene of my defeat and try again operated like an undertow in the unconscious growing steadily stronger until, on that September evening, it took command.

By next day, however, my euphoria had ebbed slightly and I was seeing this return to India as a dual challenge. Apart from the subtle, impersonal challenge of India itself, there would be the personal challenge posed by trying to achieve a successful fusion of two roles: mother and traveller. It seemed those roles must inevitably clash and at moments I doubted if they could ever be made to dovetail. Then I realised that from the outset one role had to be given precedence: otherwise the whole experience would be flawed, for both of us, by my inner conflicts. So I decided to organise our journey as Rachels apprenticeship to serious travelling.