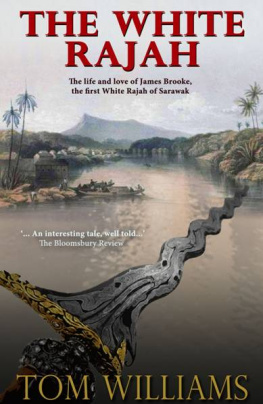

The White Rajah

Tom Williams

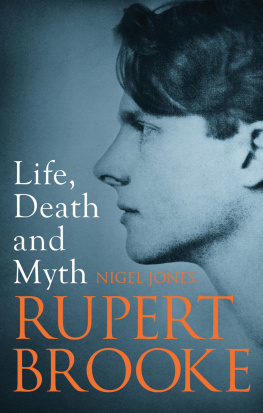

When charismatic adventurer James Brooke travels to Borneo on the schooner Royalist, he plans to make a great fortune establishing trade between the natives and the British Empire. But even in his flights of fancy, hed never imagined that he would end up rajah of his own country.

The story is told by John Williamson, a young sailor who has travelled with Brooke since he set out from England. They find themselves mixed up in Borneos civil war, political divisions, and intrigue, being forced further and further away from their dreams and ideals and struggling to establish the British presence on the island as, meanwhile, love grows between them

Based on the true story of James Brooke, the first White Rajah of Sarawak, this tale of adventure and love is set against the background of a jungle world of extraordinary beauty and savagery.

This edition published by Accent Press 2014

ISBN: 9781682990476

The rights of Tom Williams to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publishers: Accent Press Ltd, Ty Cynon House, Navigation Park, Abercynon, CF45 4SN

These stories are works of fiction. Names, characters, place, and incidents are either products of the authors imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental, apart from in cases of actual historical figures.

I can still remember the very first time I saw James Brooke.

It was in The Goat and Compasses, a low dive of an inn, even as sailors taverns go. I was there because I wanted to be alone to drink away the last of my pay and decide what I was to do for the future when the door was thrown open and in he came.

He was so much younger in those days, of course. We were all so much younger. I was scarcely a man, really, for all I thought myself cock o the walk. He was in his middle twenties, tall, good-looking with dark curly hair blowing untidily. I say good-looking but, in truth, he was one of the handsomest men I had ever seen. He was of medium height but slim and swift in his movements, and he carried himself with the easy confidence that comes with wealth. It seemed to me he brought an energy and enthusiasm into the room with him. At first I thought it was because of the red soldiers coat he wore over civilian trousers. (It was the coat of an officer of the East India Company and he had no business wearing it, having resigned his commission the previous year, but all this I was to learn later.) As he and his friends fairly skipped across to the bar, though, his gaze caught mine and the fire that glinted and shone in that glance was brighter than any red coat.

Since that night, I have seen him pass into all sorts of company joining a seamans mess, bursting into an Admirals cabin, being ceremoniously ushered into a throne room and I have so often seen the way the room lights up, charged as it were by an almost mystical energy he brings with him. By now I hardly notice it, but then I was caught staring in that light the way I have seen rabbits trapped in a lanterns beam on those nights I went lamping back in my farmhood days.

Besides him, the others seemed almost shadows. I am not even sure who was there and whom I met later. Colin Hart, I remember another lively man of about Brookes age but more solid and with the bearing of a sailor (which, indeed, he was). John Kennedy was there, too. Kennedy was an older man, dressed carefully in decent but slightly shabby clothes which told of a person in whom taste and ambition outstripped income. His bearing, though, suggested a strong man who saw life as a battlefield on which he marshalled his legions with every hope of success. There were two or three others but they were younger and, I think now, of no account. That is not to say I thought them of no account at the time, for they were clearly gentlemen, both by their clothes and by their manner. I, you must remember, was amongst the humblest class of sailors in the tavern and my experience of gentlefolk was scarce.

The party was well in drink but not, in my book, drunken. They all seemed merry, even Kennedy, in whom a certain caution sat, calculating, even in the midst of celebration. They seemed to be celebrating some good fortune and coins were hammered impatiently on the bar as ale was called for. Someone shouted for food and it was agreed they should eat in the tavern. The young gentlemen, I remember, thought this a great joke, a sailors inn being apparently somewhat inferior to their usual haunts. Brooke, though, drew Hart and Kennedy to him, an arm around each of their shoulders, and said they should break bread together in an honest meal with honest seamen and this was a fine way to celebrate a venture which would see them dining in many stranger places than this.

I had been quietly finishing my ale as I watched them. They were so alien to the world I inhabited, I was fascinated by them but, at the same time, nervous of having them about me. I decided that once I had supped my pint, I would take myself away to some lodging house and leave the gentlemen to their pleasures with their own sort.

Meanwhile, Mr Brookes party was calling for a table to be moved and more chairs to be brought up against others who, they said, would follow them. There was a great hustling and bustling and all at once one fellow, turning to gesture to a friend, struck my arm and caused me to spill my drink. I bit back my oath, for it would do me no good to swear at one of his station, and I drew myself together to depart. It was then Mr Brooke clapped me on the shoulder and set his own jug in front of me.

I will not see a fellow without a drink on our account, he said. Tell me your name.

Williamson, sir, I said, knuckling my forehead. John Williamson.

Well, Williamson, dont mind Richard. Hes a clumsy fellow at the best of times.

Richard laughed as someone started a long, disjointed story about a vase Richard had broken in some Chinese temple on a voyage they had undertaken together, and then someone else was telling a story of a Chinese temple he had seen, and all at once food was being set out and some other gentlemen were coming into the inn to join them. Someone set a slice of beef before me. I started to push it away, for clearly I was served in error, but Brooke looked up and said I was to eat. We are celebrating the purchase of a ship, he said. We are to set out for the Far East on our nautical venture and if we cannot have a sailor join our feast, then I would hazard we are in the wrong line of business.

There was more laughter at this. One or two gentlemen slapped me on the back, saying they should be proud to eat with me. More ale arrived at the table and we settled together to our meal.

Roast beef and ale have a wonderful way of hastening good fellowship, even amongst those who would not expect to keep the same society. Certainly the ale was plentiful, yet the principal actors were never drunk. Kennedy maintained always a reserve of sobriety that watched and calculated as the others talked louder and laughed longer with the passing of the evening. Brooke, although flushed and noisy, was ever aware of what was said by everyone enjoying his hospitality and moved among them with a word here and a smile there, ensuring harmony among all his guests.

I sat quiet at first, minding my station, but as the meal progressed I found myself joining in the cheer. They were, as Mr Brooke had said, celebrating the purchase of a ship, the

Next page