Barley - White Rajah

Here you can read online Barley - White Rajah full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

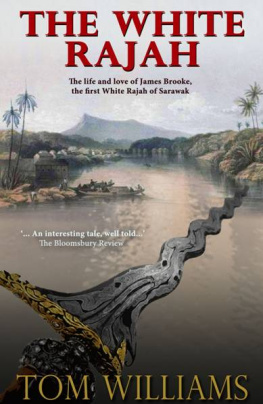

- Book:White Rajah

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

White Rajah: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "White Rajah" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

White Rajah — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "White Rajah" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

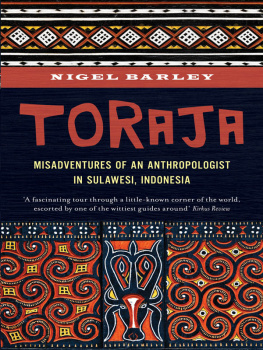

Nigel Barley is the author of a number of books on topics as diverse as cultural history and African pottery, including The Innocent Anthropologist and Dancing on the Grave. He is a curator in the Ethnography Department of the British Museum.

Praise for White Rajah

The author makes an effort to steer away from other stories about his subject that have sought to turn him into a legendary imperial icon. Nigel Barley tries hard to paint a more truthful portrait and to show James Brooke for what he was Literary Review

Praise for Nigel Barley

Nigel Barley is that rarity, a respected anthropologist with the common touch Wit and wisdom shine through his pages New Statesman and Society

He does for anthropology what Gerald Durrell did for animal collecting Daily Telegraph

Dancing on the Grave

Not a Hazardous Sport

The Innocent Anthropologist

A Plague of Caterpillars

The Duke of Puddle Dock:

Travels in the Footsteps of Stamford Raffles

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978 0 349 13985 2

Copyright Nigel Barley, 2002

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

www.hachette.co.uk

To Din

I n 1949, in a small, bleak Sarawak town called Sibu, a minor British governor was blatantly murdered in a most public fashion. Duncan Stewart had been in the job just eighteen days, the new ruler of a mix of Malays, Dayaks and Chinese in the swampy little state that hugged the north-west coast of the huge island of Borneo. As he walked with gubernatorial aplomb down a line of flag-waving Chinese schoolchildren, a young Malay named Rosly bin Dhobie stepped briskly forward and stabbed him, almost casually.

The incident figured only briefly in the UK newspapers but in Sarawak, understandably, it was regarded as a great event. A major interest was that Stewart carried on and finished the dutiful inspection of the children before anyone noted what had happened. With blood oozing between the fingers clasped to his side, he walked calmly back to his car, took off the plumed hat that was part of tropical dress uniform and asked quietly to be taken to the hospital. Pictures show the young assassin swaggering eagerly away into martyrdom, his escort hard-pressed to keep up with him. His eyes blaze with youthful moral rectitude. Rosly would be hanged on a gallows specially imported from Singapore after a swift trial unhampered by any too-delicate scrupling over his democratic and judicial rights. A picturesque element in the courtroom was the daily attendance of a body of Dayak tribesmen in full traditional wargear, who declared themselves there to support the government. Quite who the government was, however, was the whole issue. The British newspapers omitted to even mention which flag the children had been waving British or Sarawakian.

In 1945 the Japanese occupation of Sarawak had come to an abrupt end, but servants still had to be reminded to show respect by cupping their hands to their brows or hearts in Malay fashion and not by bowing and hissing as the Japanese did. Nominally in charge was the somewhat vague, effete and well-intentioned Rajah Vyner, third in a dynasty of British rulers, drawn from the Brooke family, that stretched back a hundred years. His position was distinctly odd, as a British subject who was independent ruler of a British-protected territory which paid tribute to the neighbouring state of Brunei, most of whose land it had swallowed anyway. Rajah Vyner Brooke determined that Sarawaks future lay in a constitutional adjustment with the Colonial Office, as a regularised, sanitised and bureaucratised colony, since the British alone could bring the investment needed to rebuild the shattered economy and ruined infrastructure of the little state. The Brooke philosophy of patch, make do and mend was simply no longer equal to the task. But his people were far from in agreement. Many wanted a rajah of the British Brooke dynasty to remain as their ruler; others wanted independence; very few declared themselves eager to be swallowed and digested in the maw of the British imperial machine despite its shameless use of bribery and intimidation. Rajah Vyners heir, Anthony, continued to campaign against the Rajahs cession of the territory to Britain and was finally banned from Sarawak.

There was plenty of time for all this to pass through the fevered head of Duncan Stewart as he was transported by flying boat to Singapore and, in the course of five days, his condition passed relentlessly from satisfactory to doing well to giving cause for concern to deceased. The British authorities put it about that anti-colonial posters had been ripped down throughout the colony and that Malays had fled into the jungle to avoid the righteous wrath of Dayaks. A hundred years after the founding of the state, the myth of Malay duplicity and Dayak loyalty was still doing its job. As he looked up at the changing brown, yellow and white faces that gazed down on him with concern, Duncan Stewart, like all of us, probably asked the question Why me? To answer that, he would have to go back to the beginning of the romantic and mysterious status of Sarawak, whose final victim he was, and the start of all the confusion, fighting and wrangling the curious and disquieting Englishman named James Brooke, who had created the tangled daydream of Sarawak and was the first and greatest of its white rajahs.

A childhood portrait shows a rather knowing James Brooke pouting cherubically in lace and napped velvet. From the first he was unutterably spoiled. His early years were blessed with an ample private income and hushed legal respectability, and his youth conditioned by the measured flow of imperial tribute into family coffers, for the family was above pecuniary excitement. James Brooke was born on 29 April 1803 and raised in Benares, India, as the fifth child of Thomas Brooke, an official of the Honourable East India Company and a wealthy High Court judge. Thomas is described in terms such as not really clever, precise, old-fashioned probably euphemisms for withering dullness and lack of imagination but as a good talker, meaning that he had been well finished. These qualities may have made him an ideal servant of the law but they contrast rudely with those applied to his swashbuckling son.

Curiously, the two always seem to have got along very well. Thomas Brooke was an affectionate and kindly parent, like the long-suffering father in a Jane Austen novel. If he had a fault it seems to have been that he was simply too indulgent and forbearing. It was a fault that, for most of his life, James would show too. Only at the end would he learn how to be cruel.

Understanding India is important for understanding the Brookes. It was the forge in which they hammered out their ideas of ruler and ruled. India became, to the whole Brooke dynasty, an enduring and terrible example of how not to run a country. It was too large, too professional, not based on a loyalty that was purely personal indeed, they believed that loyalty should be almost familial, and retain the rough-edged feel of the home-made. When it later came to appointing officials in his own private kingdom of Sarawak, James would always show a suspicion of both academic brilliance and bureaucratic regulation. For him a committee was a thing that kept minutes and wasted hours.

A brother, Henry, died young in the army, leaving James sole beneficiary of four sisters. Two of these would also perish early, not in India but in the dangerously pestilential environment that was nineteenth-century England. Both of his surviving sisters would marry into the Church, Emma to the Reverend Charles Johnson, to provide the stuff of future rajahs, while Margaret wed the Reverend Anthony Savage and remained childless.)

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «White Rajah»

Look at similar books to White Rajah. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book White Rajah and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.