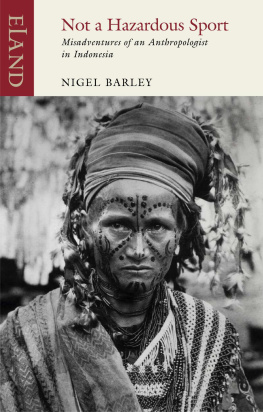

T RADITIONALLY, ANTHROPOLOGISTS HAVE WRITTEN about other peoples in the form of academic monographs. The authors of these somewhat sere and austere volumes are omniscient and Olympian in their vision. Not only do they have a faculty of shrewd cultural insight superior to that of the natives themselves, but they never make mistakes and they are never deceived by themselves or others. On the maps of alien culture they offer there are no dead ends. They have no emotional existence. They are never excited or depressed. Above all, they never like or dislike the people they are studying.

This is not such a monograph. It deals with first attempts to get to grips with a new people indeed a whole new continent. It documents false trails and linguistic incompetences, refuted preconceptions and the deceptions practised by self and others. Above all, it trades not in generalisations, but encounters with individuals.

From the strict anthropological perspective, these encounters are vitiated by the fact that they took place not in the first local tongue of the people but in Indonesian. The Republic of Indonesia has many hundreds, if not thousands, of local languages. First approaches are therefore always through the medium of the national language, and its use is a mark of the preliminary nature of the contact involved. Such contacts over the more than two years dealt with by this book nevertheless turned into relationships of real personal and emotional content.

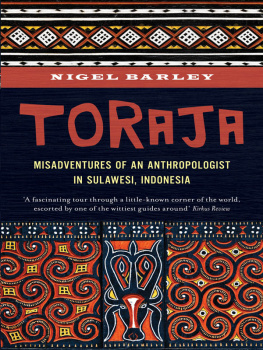

Monographs are written in reverse. They impose a spurious order on reality where everything fits. This book was written in the course of the experience it documents. A quite different work could have been constructed starting from the magnificent Torajan rice-barn that now stands in the galleries of the Museum of Mankind in London, showing how the plan to build it made ethnographic, financial and museological sense. But that is not the way it happened.

Many people helped in the project that is the matter of this book. In England, the Director and Trustees of the British Museum had the vision to finance such a speculative enterprise. Without the unflagging support and understanding of Jean Rankine and Malcolm McLeod, it could have never come to pass.

In Indonesia, thanks are due to Ibu Hariyati Soebadio of the Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. Bapak Yoop Ave and Luther Barrung of the Departemen Parpostel all of whom led me by the hand through the official channels that I could never have navigated without their continued good will. Bapak Yakob, Bupati of Tana Toraja, Bapak Patandianan of Sospol and Nico Pasaka were ever helpful. In Mamasa, Dr Silas Tarrupadang is owed warm thanks for his unstinting hospitality and assistance. Professor and Ibu Abbas of Hasanuddin University went out of their way to help me in a time of dire need. One anti-acknowledgement is due to Bapak W. Arlen of the Immigration Office, Ujung Pandang.

I am also grateful to H. E. Bapak Suhartoyo and Bapak Hidayat of the Indonesian Embassy in London. A special vote of thanks is due to Bapak W. Miftach, also of the Indonesian Embassy in London, for his sustained support, assistance and friendship throughout this project.

The Torajan Foundation of Jakarta especially Bapak J. Parapak and Bapak H. Parinding took a warm personal interest in the Torajan exhibition from its inception and acted as sponsors, as did Garuda Indonesia.

Without the cheerful friendship, assistance and understanding of Sallehuddin bin Hajji Abdullah Sani, this project would not have been conceived and could not have been executed.

Above all, thanks are due to the many ordinary Torajan men and women who took me to their hearts and aided me without thought of reward or personal convenience.

Nigel Barley

A NTHROPOLOGY IS NOT A HAZARDOUS SPORT . I had always suspected that this was so but it was comforting to have it confirmed in black and white by a reputable insurance company of enduring probity. They, after all, should know such things.

The declaration was the end result of an extended correspondence conducted more in the spirit of detached concern than serious enquiry. I had insured my health for a two-month field-trip and been unwise enough to read the small print. I was not covered for nuclear attack or nationalisation by a foreign government. Even more alarming, I was covered for up to twelve months if hijacked. Free-fall parachute jumping was specifically forbidden together with all other hazardous sports. But it was now official: Anthropology is not a hazardous sport.

The equipment laid out on the bed seemed to contest the assertion. I had water-purifying tablets, remedies against two sorts of malaria, athletes foot, suppurating ulcers and eyelids, amoebic dysentery, hay fever, sunburn, infestation by lice and ticks, seasickness and compulsive vomiting. Only much, much later would I realise that I had forgotten the aspirins.

It was to be a stern rather than an easy trip, a last pitting of a visibly sagging frame against severe geography where everything would probably have to be carried up mountains and across ravines, a last act of physical optimism before admitting that urban life and middle age had ravaged beyond recall.

In one corner stood the new rucksack, gleaming iridescent green like the carapace of a tropical beetle. New boots glowed comfortingly beside it, exuding a promise of dry strength. Cameras had been cleaned and recalibrated. All the minor tasks had been dealt with just as a soldier cleans and oils his rifle before going into battle. Now, in pre-departure gloom, the wits were dulled, the senses muted. It was the moment for sitting on the luggage and feeling empty depression.

I have never really understood what it is that drives anthropologists off into the field. Possibly it is simply the triumph of sheer nosiness over reasonable caution, the fallibility of the human memory that denies the recollection of how uncomfortable and tedious much of field-work can be. Possibly it is the boredom of urban life, the stultifying effect of regular existence. Often departure is triggered by relatively minor occurrences that give a new slant on normal routine. I once felt tempted when a turgid report entitled Applications of the Computer to Anthropology arrived on my desk at the precise moment I had spent forty minutes rewinding a typewriter ribbon by hand because my machine was so old that appropriate ribbons were no longer commercially available.

The point is that field-work is often an attempt by the researcher to resolve his own, very personal problems, rather than an attempt to understand other cultures. Within the profession, it is often viewed as a panacea for all ills. Broken marriage? Go and do some field-work to get back a sense of perspective. Depressed about lack of promotion? Field-work will give you something else to worry about.

But whatever the cause, ethnographers all recognise the call of the wild with the certainty that Muslims feel about the sudden, urgent need to go to Mecca.

Where to go? This time, not West Africa but somewhere fresh. Often I had been asked by students for advice on where to go for field-work. Some were driven by a relentless incubus to work on one topic alone, female circumcision or black-smithing. They were the easy ones to counsel. Others had quite simply fallen in love with a particular part of the world. They, too, were easy. Such a love affair can be as good a basis for withstanding the many trials and disappointments of ethnography as any more stern theoretical obsession. Then there was the third, most difficult group, into which I myself seemed now to fall what a colleague had unkindly termed the SDP of anthropology those who knew more clearly what they wanted to avoid than what they wished to seek.