S O. Y OU HAVE NEVER BEEN TO OUR COUNTRY BEFORE ? The Cameroonian immigration officer looked at me with suspicious eyes and flicked listlessly through my passport. Stains of perspiration, the shape of Africa, stretched down his shirt under the armpits, for this was Duala at the height of the hot, dry season. Each finger left a brown sweat stain on the pages.

Thats right. I had learned never to disagree with African officials. It always ended up taking more time and costing more effort than simple passive acquiescence. This was an expedient explained to me by an old French colonial as adjusting the facts to fit the bureaucracy.

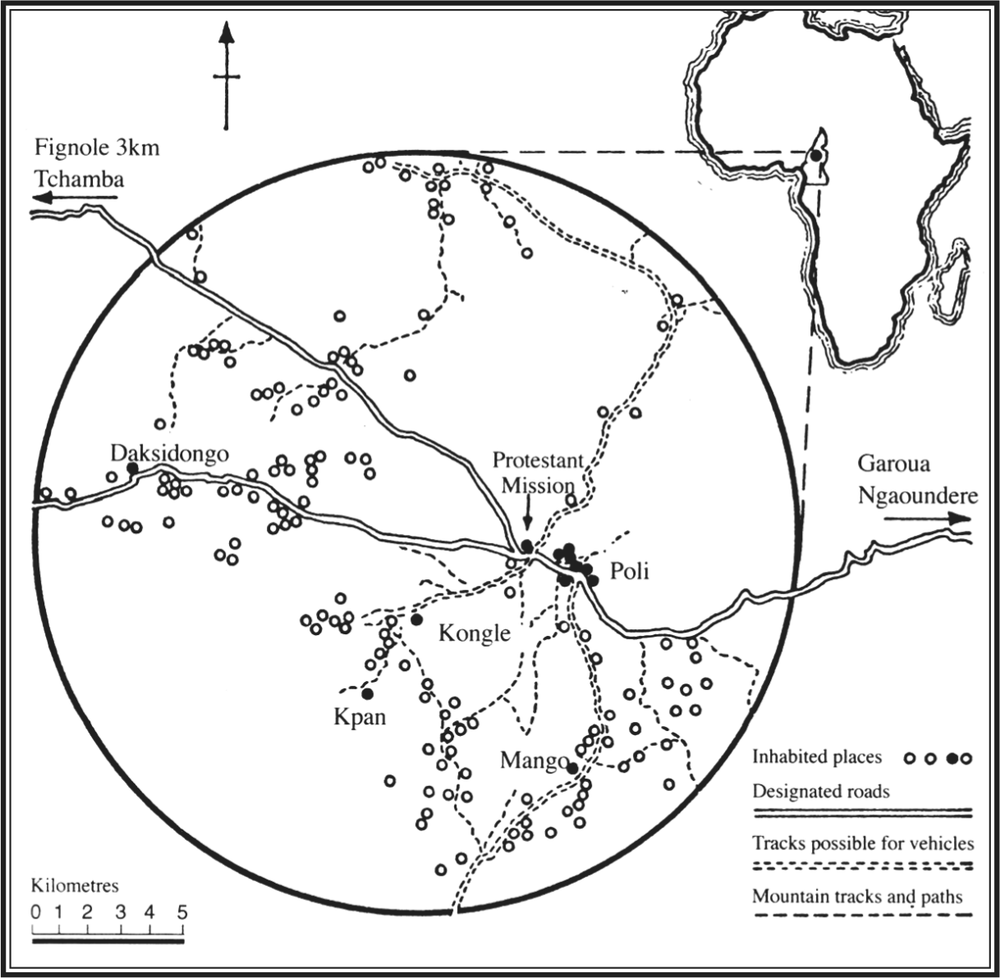

In reality, this was not my first visit but my second. Previously I had spent some eighteen months in a mountain village in the north studying a tribe of pagans as their resident anthropologist Since, however, my passport had been stolen by the enterprising rogues of Rome there was no incriminating evidence in the form of old visas to give me away. I congratulated myself on the bland uninformativeness of my nice new passport. This should all be rather easy. Should I confess to a prior visit, I would immediately be required to engage in an orgy of bureaucracy, giving dates of entry to and departure from the country, number of previous visa and so on. The sheer unreasonableness of requiring a mere traveller to carry all this in his head would serve as no defence.

Wait here. I was gestured peremptorily to one side and my passport was taken away to disappear behind a screen. A face appeared over it and scrutinized me. I heard a rustling of pages. I imagined myself being sought in those thick volumes of prohibited persons I had seen at the Cameroonian Embassy in London.

The official returned and began a minute inspection of the travel documents of a Libyan of deeply shifty appearance. This gentleman claimed to be a general entrepreneur and possessed an implausible amount of luggage. With breathtaking shamelessness, he had given as the reason for his visit the search for commercial possibilities to benefit the Cameroonian people. To my great surprise, he was waved through without further formality. There followed a whole string of wildly overblown people, a farcical collection of thieves, rogues, art-dealers all masquerading as tourists. All were accepted at face value. Then there was me.

The official shuffled his papers in a leisurely way. He was taking his time. Having established to his satisfaction his dominance in our relationship, he favoured me with a look heavy with supercilious shrewdness. You, monsieur, will have to see the chief inspector.

I was led through a door and down a corridor clearly not for public consumption and given a hard seat in a bare room devoid of all comfort. The lino was scuffed and stained with a thousand sins. It was swelteringly hot.

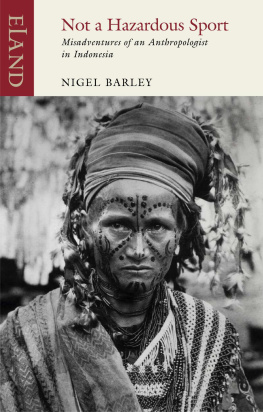

We are all overdrawn at the moral bank. The slightest challenge by authority draws on deep wells of guilt. In the present case, my position was more than a little shaky. In my first visit to the Dowayos, my mountain tribe, I had learned of the centrality of the circumcision ceremony to their whole culture. But, since it only takes place at six- or seven-year intervals, I had never been able to witness it. True, I had written down descriptions and photographed parts of the ceremony that are reproduced at other festivals, but the real thing had escaped me. Local contacts had tipped me off a month ago that the ceremony was imminent. Who knew when the ceremony would take place again if ever? It was a unique chance and one to be seized. I knew from previous experience that there was no chance of getting permission in time to do recognized fieldwork; I was therefore entering the country as a simple tourist. For myself, there was no inherent dishonesty in this; I would simply be doing what all tourists did take photographs. At the ceremony, there would certainly be other tourists, happily snapping away for the scrapbook. It seemed unreasonable that I, as an anthropologist, should not be allowed to do what a vacationing accountant could do.

But now it was clear that they had found out. How? I could not believe that anyone ever read all those pieces of paper I had filled in at the embassy and airport. I comforted myself with the thought that since I was still 1,000 miles away from Dowayoland I could not have committed anything but a trivial offence.

The waiting-room of the chief inspector is not the best of addresses. It would instil despair into those with the most cheery of dispositions. The long delay provided new food for paranoia. I began to fear for my luggage. (A vision of grinning customs men, hands dipping in, dividing up my raiment. See. This luggage has not been claimed. We may take it for ourselves.)

At length. I was shown into a spartan office. Seated at the desk was a dapper man with a military moustache and a manner to match. He smoked a long cigarette, the smoke curling up towards a wobbly ceiling-fan set so low as to decapitate any Nordic miscreant who should enter. I was unsure whether to adopt a pose of outraged innocence or French camaraderie. Not knowing the evidence against me, I thought silly-arse Englishman would be the best bet. The English are fortunate indeed that most peoples expect them to be a little odd and quite hopeless at documentation.

The dapper official waved my passport, already glaucous with cigarette ash.

Monsieur, it is the problem of South Africa.

This really took me aback. What had happened? Was I to be expelled in revenge for some English cricket teams fraternizations? Was I being taken for a spy?

But I have no link with South Africa. I have never even been there. I dont even have relatives there.

He sighed. We do not permit people to enter our country who have been comforting the fascist, racist clique that terrorizes that land, resisting the just aspirations of oppressed peoples.

But

He held up a hand. Let me finish. To prevent our knowing who has and has not entered that unfortunate country, many regimes are misguided enough to issue their citizens with new passports after they have visited South Africa so that there are no incriminating visas in their documentation. You, monsieur, have just been issued with a brand-new passport though your previous one was still valid. It is clear to me that you have been to South Africa.

A lizard scuttled across the wall and fixed me accusingly with its beady eye.

But I havent.

Can you prove it?

Of course I cant prove it.

We pushed back and forth the logical problem of proving a negative until quite suddenly the inspector wearied of our rough-hewn philosophy. With true bureaucratic flare, he proposed a compromise. I would verbally declare my readiness to make a written declaration that I had never been to South Africa. This would suffice. The lizard nodded its enthusiastic agreement.

Outside, my luggage lay in a heap, rejected and despised. As I stooped to carry it to the customs desk, my arm was seized by a man of huge girth. Psst, patron, he breathed. You are going on to the capital tomorrow? I nodded.

When you check in your luggage, or when you come back, you ask for me, Jacquo. No weight limit. You just buy me a beer. He sidled away.

The customs officer was petulant at my long delay with other officials. In pique, he refused even to consider my luggage and gestured me through to where I knew the taxi-drivers lurked.

Somewhere in Africa, there must be taxi-drivers who are kind, peaceable, knowledgeable, honest and courteous. Alas, I have never found this place. The newcomer may expect, with reasonable certainty, to be robbed, cheated and abused. On a previous visit to Duala, before I was acquainted with the geography of the town, I had taken a taxi to a place that was less than half a mile away. The driver had pretended it was a good ten miles distant, charged a huge fare and driven me around in circles until I lost all sense of direction, profiting from my hire to deliver newspapers to outlying districts. Only when I sought to make my way back, did I glimpse the unmistakeable shape of my hotel a mere ten minutes walk away. Taking an African taxi is almost always hard work. Often, it is much easier to walk.