The past is not dead, but is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make.

~ WILLIAM MORRIS

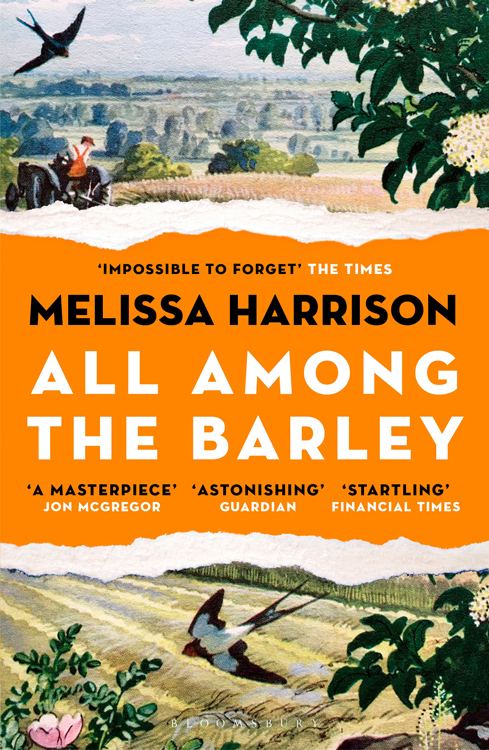

Fiction

Clay

At Hawthorn Time

Non-fiction

Rain: Four Walks in English Weather

As editor

Spring: An Anthology for the Changing Seasons

Summer: An Anthology for the Changing Seasons

Autumn: An Anthology for the Changing Seasons

Winter: An Anthology for the Changing Seasons

Last night I lay awake again, remembering the day the Hunt ran me down in Hulver Wood when I was just a girl. It was December, as it is now, and I had ventured out into the icy afternoon to cut some green boughs for the house. None of the others minded much about decorations, but I loved the way the firelight flickered on the glossy leaves of holly I always hung above the parlour hearth.

Frost had hardened the furrows of the ploughland and at the fields margins ice stood in the cart ruts, bubbled and opaque. I had a sack, and a set of pruning-shears, and I wore a pair of my brothers old work gloves on my chilled and clumsy hands. As I walked, a white owl kept pace with me, drifting silently at head-height on the other side of the hedge; perhaps it hoped I would startle some blood-warm creatures from its tangled base.

It was dim that afternoon in Hulver Wood, and no birds sang. I pushed deeper and deeper in, stopping at the jill hollies with their blood-red berries and wriggling my toes inside my boots to keep off the frozen ache of the ground.

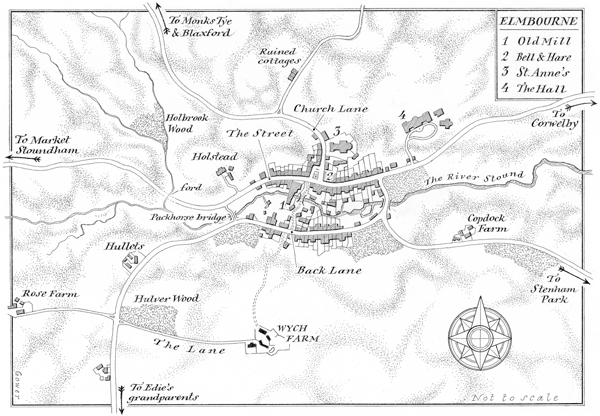

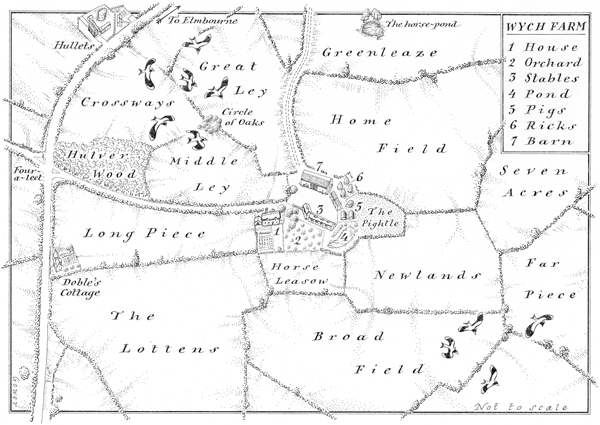

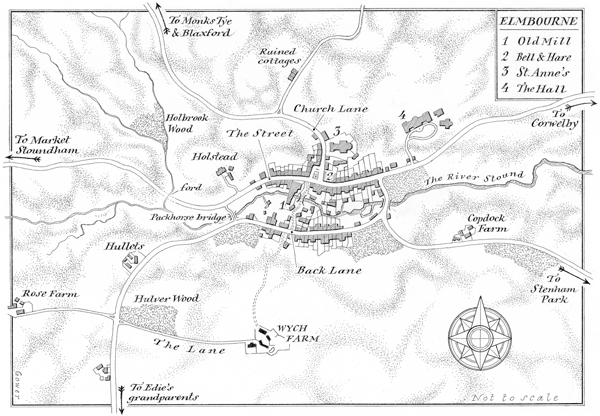

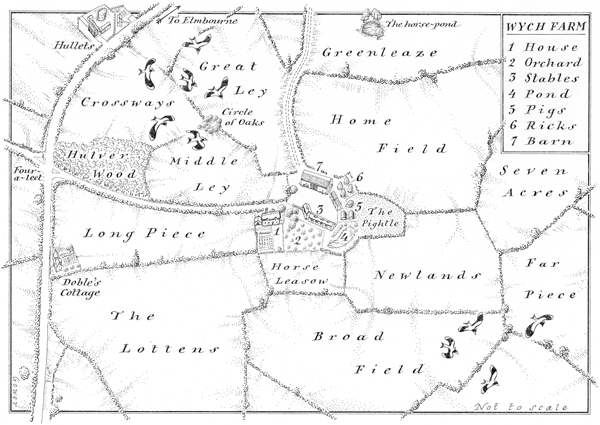

The sound of the gone away, blown close, cleaved the still December air. Heart pounding, I crushed the prickly leaves down into the hessian and twisted a rough knot with trembling hands. But they were far too close already, and from the top of the wood bank I saw them streaming towards me from The Lottens into Long Piece: the hounds ahead and questing in full cry, the pink- and red-coated riders urging the thundering horses on behind.

Get on! Go! shouted the Master of Hounds as the first of the baying dogs reached the trees. For Gods sake, girl, will you move!

But trembling, I froze, and the pack broke around me like water before my legs could carry me out of the way.

My name is Edith June Mather and I was born not long after the end of the Great War. My father, George Mather, had sixty acres of arable land known as Wych Farm; it is somewhere not far from here, I believe. Before him my grandfather Albert farmed the same fields, and his father before him, who ploughed with a team of oxen and sowed by hand. I would like to think that my brother Frank, or perhaps one of his sons, has the living of it now; but a lifetime has passed since I was last on its acres, and because of everything that happened I have been prevented from finding out.

I was an odd child, I can see now certainly by the phlegmatic, practical standards of the farming families thereabouts. I preferred the company of books to other children, and was frequently chided by my parents after leaving my tasks half-done, distracted by the richer, more vivid world within my head. And sometimes I talked to myself out loud without meaning to, usually as a way of drowning out a thought or a memory I didnt want to have. Father would sometimes tap his head and call me touched only in fun, Im sure but perhaps, looking back, he was right.

I was thirteen in 1933, the year our district began to endure its famous or infamous drought. It crept up on us: the hay came in well, and when the rick was thatched Father was pleased, because he knew it was dry and wouldnt spoil; this meant that the horses would have enough fodder to last the winter, and he would not have to buy any in. But without any rain the field drains ran dry and by August even the horse-pond by the house had shrunk to a thick green scum. I remember John Hurlock, our horseman, taking buckets of well-water to Moses and Malachi when they came in from the fields at three oclock; I can see as though it were yesterday how greedily and noisily the great horses drank, how at last he would fill the buckets again and fling the water over their twitching flanks, washing away the white rime of sweat from their chestnut coats. Oh, my beloved creatures, how they must have missed walking into the cool horse-pond, as they always had, and drinking their fill.

Frank was sixteen by then, and doing a mans work on the farm; Father was starting to rely on him almost as much as he did on John. My sister Mary, who had married Clive that spring, already had a baby boy, and although Mother harnessed our little pony Meg to the trap and drove over to Monks Tye once a week with a loaf or a suet pudding, we saw little of her at Wych Farm. With Mary gone I felt strangely suspended, as though awaiting what would come next although I couldnt have told you what that was. It was like hide-and-seek, when youre waiting for someone to find you; but the game had gone on for too long.

Of course, the drought meant that the cornfields suffered, and that year the harvest was down, our wheat barely sixteen bushels to the acre.

Seven Acres will lie fallow next year, Father said as John and Doble, our yardman, came in for their supper after the last of the corn was in. It wasnt what you might call a Harvest Home, but there was ale, and a ham, and boiled batter pudding, and Mother had twisted a few ears of barley into a rough figure and set it on the kitchen table. Opposite me Frank glanced up, alert, at Fathers words. The men took their places, and John remarked that Seven Acres had lain fallow only the year before.

Do you think to tell me how to farm? asked Father; but John did not reply. Mother sat down, I mumbled Grace, and we began to eat.

The autumn of that year was the most beautiful I can remember. For weeks after harvest-tide the weather stayed fine, and only slowly that year did summers warmth leave the earth.

In October, Wych Farms trees turned quickly and all at once, blazing into oranges and reds and burnished golds; with little wind to strip them the woods and spinneys lay on our land like treasure, the massy hedgerows filigreed with old-mans-beard and enamelled with rosehips and black sloes. Along the winding course of the River Stound the alder carrs were studded with earthstars and chanterelles and dense with the rich, autumnal stink of rot; but crossing Long Piece towards The Lottens the sky opened into austere, equinoctial blue, where flocks of peewits wheeled and turned, flashing their broad wings black and white.

At dawn, dew silvered the spiders silk strung between the grass blades in our pastures so that the horses left trails where they walked, like the wakes of slow vessels in still water. At last, wintering fieldfares and thrushes stripped the berries from the lanes, and at night the four tall elms for which the farm was named welcomed their cold-weather congregations of rooks.

The dew dampened the stubble in the parched cornfields, drawing from it a mocking green aftermath that had Grandfather recalling the flock of purebred ewes that once were overwintered on the land.

Its not worth the shearing of them these days, Father said. Ive told you that.

Next page