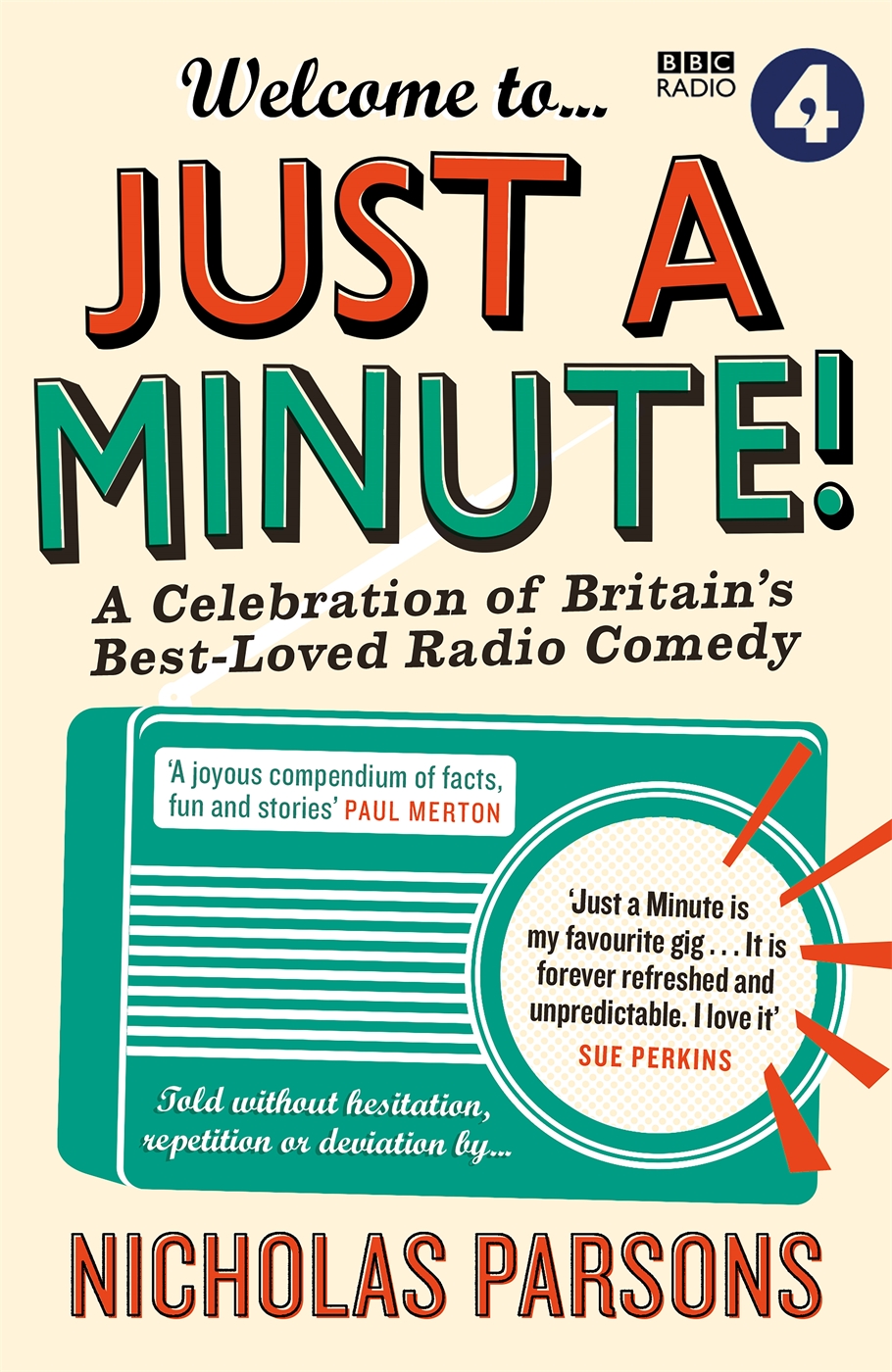

Published in Great Britain in 2014 by Canongate Books Ltd,

14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

www.canongate.tv

This digital edition first published in 2014 by Canongate Books

Copyright Nicholas Parsons, 2014

Edited by David Wilson

Design by James Alexander at Jade Design

Contribution on p. 81 2014, Gyles Brandreth

Contribution on p. 211 2014, Jenny Eclair

Contribution on p. 284 2014, Graham Norton

Contribution on p. 369 2014, Sue Perkins

The moral right of the author has been asserted

By arrangement with the BBC

The BBC logo is a trade mark of the British Broadcasting Corporation and is used under licence

BBC logo BBC 1996

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The BBC and the publisher apologise for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78211 247 1

eISBN 9781782112488

To the late Sir David Hatch, without whose talent and commitment Just a Minute would never have been launched on to the airwaves.

Contents

Preface

I do not like surprise parties when I am the one to be surprised, especially when I have been warned in advance. It was October 2013. I had just celebrated my 90th birthday with a magnificent party organised by my wife, Annie, and myself at the Churchill Hyatt Hotel, Portman Square, in Londons West End. We had invited over 200 guests, family, close friends and many show-business colleagues and acquaintances. It was a huge success and a memorable occasion, with wonderfully witty speeches from my friends Paul Merton and Gyles Brandreth, and a clever musical parody about me from Kit Hesketh-Harvey. My own speech was well received and it was an exceptionally enjoyable, even emotional, evening. Various newspapers and magazines covered the event, and my anxiety that advertising my advanced years would inhibit prospects of future work engagements proved wrong. In fact it turned out to have the reverse effect. I received many more requests and enquiries than usual.

I was overwhelmed with cards and gifts, and the last thing I then wanted was this surprise party that could only be an anti-climax. Annie, who was in on the secret, refused to give me a clue as to whom was organising the event. If you have warning of these occasions, as a performer you can prepare some thoughts on what you might say in your thank you speech to ensure you respond in appropriate style. I reluctantly went along with the subterfuge. My assumption was that the invitation was from one of the charities for which I actively work. Facetiously I suggested to Annie that if the party was to surprise me, I could surprise them by going in my pyjamas. She firmly pointed out that I should wear something smart and formal.

The hire car duly arrived. The driver had already been madeaware of what was happening, so we set off from our London flat in silence. All my preconceived ideas of where I might be going turned out to be incorrect as he took us to the outside of the main entrance of Broadcasting House in Portland Place. They dont run charity functions here, I thought. Inside we were greeted by Trudi Stevens, the assistant to the producer of Just a Minute, who led us up to the Council Chamber, the central meeting place for BBC executives. Trudi ushered me into this spacious room, where there were a hundred people: actors, writers, producers and senior staff. They gave me a huge round of applause as I entered. I was overwhelmed. I stood there speechless. I recognised a lot of the faces, professional friends and others with whom I had worked. Someone had undertaken research and discovered that I had made my first professional broadcast 72 years ago performing impersonations of James Stewart and Charles Boyer on a radio variety show called Carroll Levis Carries On as one of what the Canadian showman called his discoveries new performers whom he tipped for success. At around the same time I was also playing small roles in productions at Glasgow BBC. This was the city in which I had been based during the War, serving an apprenticeship with a firm on Clydebank that made pumps for ships, important work for the war effort and a reserved occupation. I was endeavouring to become an engineer while dreaming of becoming a full-time entertainer.

In fact over the years since then I have rarely been off BBC radio. At different times either guesting in plays, performing in variety shows, undertaking a long spell in the BBC Drama Reparatory Company, appearing in a series of Much-Binding-in-the-Marsh playing comedy characters, partnering my long-term colleague Arthur Haynes in his radio series and presenting the satirical programme Listen to this Space, a show I devised and for which I received the Radio Personality of the Year award. Also, we were just about to celebrate the 46th anniversary of Just a Minute, a programme with which I have been associated since the pilot show in December 1967. I have not missed a single recording, which now amounts to almost 900 performances.

This party was to celebrate all this and more. It was a truly moving occasion and I was overwhelmed that the BBC had decided to honour me in this way. There were some brief speeches, including Paul Merton, who sent me up in his usual delightfully humorous way, and then Tilusha Ghelani, one of the producers of Just a Minute, played a tape that she had gone to a great deal of trouble to prepare. It consisted of some of the many humorous moments from the archives of Just a Minute, including an embarrassing one in which I had made an unintentional verbal slip known as a Spoonerism, referring to Tilusha as Gilusha Tilhani.The guests loved it all and laughed affectionately at the fun that was being had at my expense.

Then I was asked to say a few words. It is always a challenge when speaking to your own profession, especially when you have nothing prepared. On this occasion it was easier than I could have imagined. It was such a warm and responsive audience, all of whom were there out of affection to pay a tribute to me. It was certainly the most emotional experience of my professional life. I was deeply touched that so many show-business friends and colleagues had found time in their busy lives to assemble secretly to drink my health and toast my career, including the Director General. We humble thespians do not expect such accolades!

I mingled and talked with the many guests, hoping the party would never end. There were some lovely moments and over-the-top compliments. I just wanted to thank everyone personally for surprising me in such a delightful way. There was one particularly touching incident when Emma Freud, a charming and talented broadcaster and writer, gave me a gift of her fathers witty articles collected together in book form. I had known Emma since she was a little girl as I had been very friendly with Clement. I was not only at school with him, St Pauls, but he had employed me regularly to work in cabaret at his Royal Court Theatre Club in Sloane Square. I even socialised with him when he entertained my wife and I at his home in St Johns Wood, where he cooked the most amazing dinners. He was, of course, a trained chef.

Emmas thoughtful gift touched me greatly. As she presentedthe book, Emma sweetly said that she knew her dad had become grumpy with me as he grew older, but the feeling did not extend to the rest of the Freud family. I was delighted to hear such warmth and reassurance. In Clements later years his attitude had changed from one of friendship to something approaching disdain. The reasons for this stemmed from the difference of opinion we each held over how