Steven Pinker is the Johnstone Family Professor in the Department of Psychology at Harvard University. Until 2003, he taught in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT. He conducts research on language and cognition, writes for publications such as the New York Times, Time and Slate, and is the author of six books, including The Language Instinct, How the Mind Works and The Blank Slate.

STEVEN PINKER

THE SEVEN

WORDS YOU

CANT

SAY ON

TELEVISION

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, CamberwelL Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank,

Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

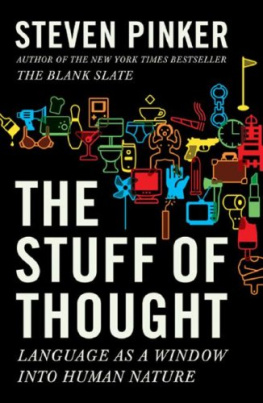

First published in The Stuff of Thought in the United States of America

by Viking Penguin 2007

First published in The Stuff of Thought in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2007

This extract published in Penguin Books 2008

I

Copyright Steven Pinker, 2007

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Grateful acknowledgement is made for permission to reprint excerpts from the following

copyrighted works: This Be the Verse from Collected Poems by Philip Larkin. Copyright

1988, 2003 by the Estate of Philip Larkin. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Strauss and

Giroux, LLC and Faber and Faber Ltd

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

978-0-14-188983-2

Freedom of speech is a foundation of democracy, because without it citizens cant share their observations on folly and injustice or collectively challenge the authority that maintains them. Its no coincidence that freedom of speech is enshrined in the first of the ten amendments to the Constitution that make up the Bill of Rights, and is given pride of place in other statements of basic freedoms such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights.

Just as clearly, freedom of speech cannot be guaranteed in every circumstance. The U.S. Supreme Court recognizes five kinds of unprotected speech, and four of the exclusions are compatible with the rationale for enshrining free speech as a fundamental liberty. Fraud and libel are not protected, because they subvert the essence of speech that makes it worthy of protection, namely, to seek and share the truth. Also unprotected are advocacy of imminent lawless behavior and fighting words, because they are intended to trigger behavior reflexively (as when someone shouts Fire! in a crowded theater) rather than to exchange ideas.

Yet the fifth category of unprotected speechobscenityseems to defy justification. Though some prurient words and images are protected, others cross a vague and contested boundary into the category of obscenity, and the government is free to outlaw them. And in broadcast media, the state is granted even broader powers, and may ban sexual and scatological language that it classifies as mere indecency. But why would a democracy sanction the use of government force to deter the uttering of words for two activitiessex and excretionthat harm no one and are inescapable parts of the human condition?

In practice as well as in theory, the prosecution of obscene speech is a puzzle. Throughout history people have been tortured and killed for criticizing their leadership, and that is the fate of freethinkers in many parts of the world today. But in liberal democracies the battle for free speech has mostly been won. Every night millions of people watch talk-show hosts freely ridiculing the intelligence and honesty of the leaders of their nation. Of course, eternal vigilance is the price of liberty, and civil libertarians are rightly concerned with potential abridgments of speech such as those in copyright law, university speech codes, and the USA Patriot Act. Yet for the past century the most famous legal battles over free speech have been joined not where history would lead us to expect themin efforts to speak truth to powerbut in the use of certain words for copulation, pudenda, orifices, and effluvia. Here are some prominent cases:

In 1921, a magazine excerpt from James Joyces Ulysses was declared obscene by an American court, and the book was banned in the United States until 1933.

D.H. Lawrences Lady Chatterleys Lover, written in 1928, was not published in the United Kingdom until 1960, whereupon Penguin Books was prosecuted (unsuccessfully) under the Obscene Publications Act of 1959.

Lady Chatterley was also banned from the United States, together with Henry Millers Tropic of Cancer and John Clelands Fanny Hill. In a series of court decisions reflecting the changing sexual mores of the 1960s, the bans were overturned, culminating in a Supreme Court ruling in 1973

Between 1961 and 1964, the comedian Lenny Bruce was repeatedly arrested for obscenity and banned from performing in many cities. Bruce died in 1966 while appealing a four-month sentence imposed by a New York court, and was finally pardoned by Governor George Pataki thirty-seven years after his death.

The Pacifica Radio Network was fined in 1973 by the Federal Communications Commission for broadcasting George Carlins monologue Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television. The Supreme Court upheld the action, ruling that the FCC could prohibit indecent language during hours when children might stumble upon a broadcast.

The FCC fined Howard Sterns popular radio program repeatedly, prompting Stern to leave broadcast radio in 2006 for the freedom of satellite radio. Many media experts predicted that it would be a tipping point in the popularity of that medium.

Other targets of sanctions include Kenneth Tynan, John Lennon, Bono, 2 Live Crew, Bernard Malamud, Eldridge

The persecution of swearers has a long history. The third commandment states, Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain, and Leviticus 24:16 spells out the consequences: He that blasphemeth the name of the Lord shall be put to death. To be sure, the past century has expanded the arenas in which people can swear. As early as 1934, Cole Porter could pen the lyric Good authors, too, who once knew better words / Now only use four-letter words / Writing prose. Anything goes. Most of the celebrity swearers of the twentieth century prevailed (if only posthumously), and many recent entertainers, such as Richard Pryor, Eve Ensler, and the cast of South Park, have cussed with impunity. Yet its still not the case that anything goes. In 2006 George W. Bush signed into law the Broadcast Decency Enforcement Act, which increased the fines for indecent language tenfold and threatened repeat offenders with the loss of their license.