Introduction

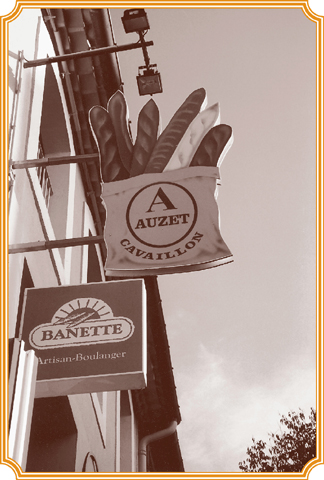

I N CAVAILLON , there are seventeen bakers listed in the Pages Jaunes, but we had been told that one A establishment was ahead of all the rest in terms of choice and excellence, a veritable a depain. At Chez Auzet, so they said, the baking and eating of breads and pastries had been elevated to the status of a minor religion.

That was written in 1988, scribbled in one of the notebooks that were eventually turned into A Year in Provence. And ever since my first visit, the boulangerie Auzet has been one of my favorite places in Cavaillon.

It is not a mere shop, and certainly not somewhere for the hurried, in-and-out purchase. That would be to miss half the pleasure of going there, a pleasure that starts even before entering the premises. You pause for a moment on the threshold. You close your eyes, and, taking a long, deep breath (through the nose, of course),you inhale the parfum de la maison. Fresh, warm, buttery, doughyit is one of the oldest, most appetizing and evocative smells in the world, primitive and infinitely comforting.

Gerard Auzet, who has taken over the business from Roger, his father, has become a friend. Whenever I go into the boulangerie, he greets me with a firm, floury handshake and a cup of coffee. Usually, we talk about bread. But one morning, he had more on his mind than the day's new batch of croissants, boules, and fougasses. He had a small but interesting problem.

Foreigners, many foreigners, had been coming to the bakery after reading about it, and it seemed they wanted more than bread. They also wanted knowledge: ingredients, recipes, tipsanything that might help them to bake their own bread a la facon d'Atqet when they returned home to San Francisco, Tokyo, Munich, London, or Amsterdam.

Gerard, being a generous and obliging man, started to give demonstrations for his overseas customers. Once a week, he would take a group of them into the baking room at the back of the shop and give them a two-hour class in bread making: how to shape the dough into baguettes, boules, and batards, how to decorate the dough with patterns of stripes and indentations, how to finish off the ends with satisfying blunt curvesand, finally, how to bake.

The demonstrations became more and more popular. But something was missing. Auzet's disciples, the students, kept asking for a reminder of their lesson to take home with them, a written reference, a kind of guide to basic baking.

Voila leprobleme, Gerard said to me. Of course, they have my recipes. But I'd like to give them more than just a few sheets of paper. Perhaps some history, one or two anecdotes, a few hintsyou know, a proper souvenir. A little book.

I think that's a delightful idea, I said.

Yes, said Gerard. And you can write it for me.

And so I have, though the expertise is his.

P.M., January 2005

The Birth of a Loaf

C AVAILLON , the melon capital of France (and of the world, according to the local melon fraternity), is a market town of some 23,000 inhabitants, about a thirty-minute drive from Avignon. By day, it's a lively, crowded place. Cars prowl the streets in search of a parking spot, housewives sniff and prod the glistening piles of fruit and vegetables laid out on sidewalk stands shaded by striped awnings, cafe regulars study newspapers over their morning beers as dogs sidle between the tables hoping to find a fallen croissant. The sounds of laughter, vigorous argument, and les top hits of Radio Vaucluse burst out through open doors and windows.

That was how I knew Cavaillon, and how I always thought of it, until I was invited to take a look behind the scenes of the Auzet bakery by the patron himself. It was to be a working visit. I wanted to see bakers in action. I wanted to witness mounds of dough being transformed into loaves. I wanted to run my fingers through the flour, squeeze a warm boule or two, and generally soak up the atmosphere.

That was no problem, Gerard Auzet told me. I could have the freedom of the bakery while it was still calm and uncrowded. He suggested that I turn up for work, like everyone else, at four a.m. He could guarantee I'd have no trouble parking.

Cavaillon at four on that August morning was cool and ghostly. There were no cars, no noise, no people, no hint of the heat that would come with the morning sun. I was aware of hearing sounds one seldom hears in a busy town: the ticking of my car's engine as it cooled, the wailing of a lovelorn cat, the click of my own footsteps. I walked past shuttered stores and groups of cafe chairs and tables that had been chained up on the pavement for the night. It felt strange to have the street to myself.

Gerard was waiting for me at the end of the Cours Bournissac, standing in a pool of light outside the entrance to his bakery. He was more cheerful than any man had a right to be at that time of the morning.

We've already started, he said. But you haven't missed much. Come on in.

It was still too early for the addict's fix, the warm and heavenly whiff of just-baked bread. That would come in an hour or so, filling the bakery, drifting out through the door, causing nostrils to twitch in anticipation. The very thought of it made me hungry.

For the first time, I saw the bakery in a state of undress, the shelves bare. By six a.m. those shelves would be filling up with loavestall and thick, long and slender, plump and round, plain and fancy, whole wheat, rye, bran, flavored with garlic or Roquefort cheese, studded with olives or walnutsthe twenty-one varieties that are baked and sold each day. (If none of these is exactly what you want, the Auzet bakers can also supply made-to-order breads; these include bouillabaisse bread, saffron bread, onion bread, apricot bread, and, for those who like nibbling monograms, personalized bread rolls. You name it, they bake it.)