Eating peas in the field with Farmer Mark.

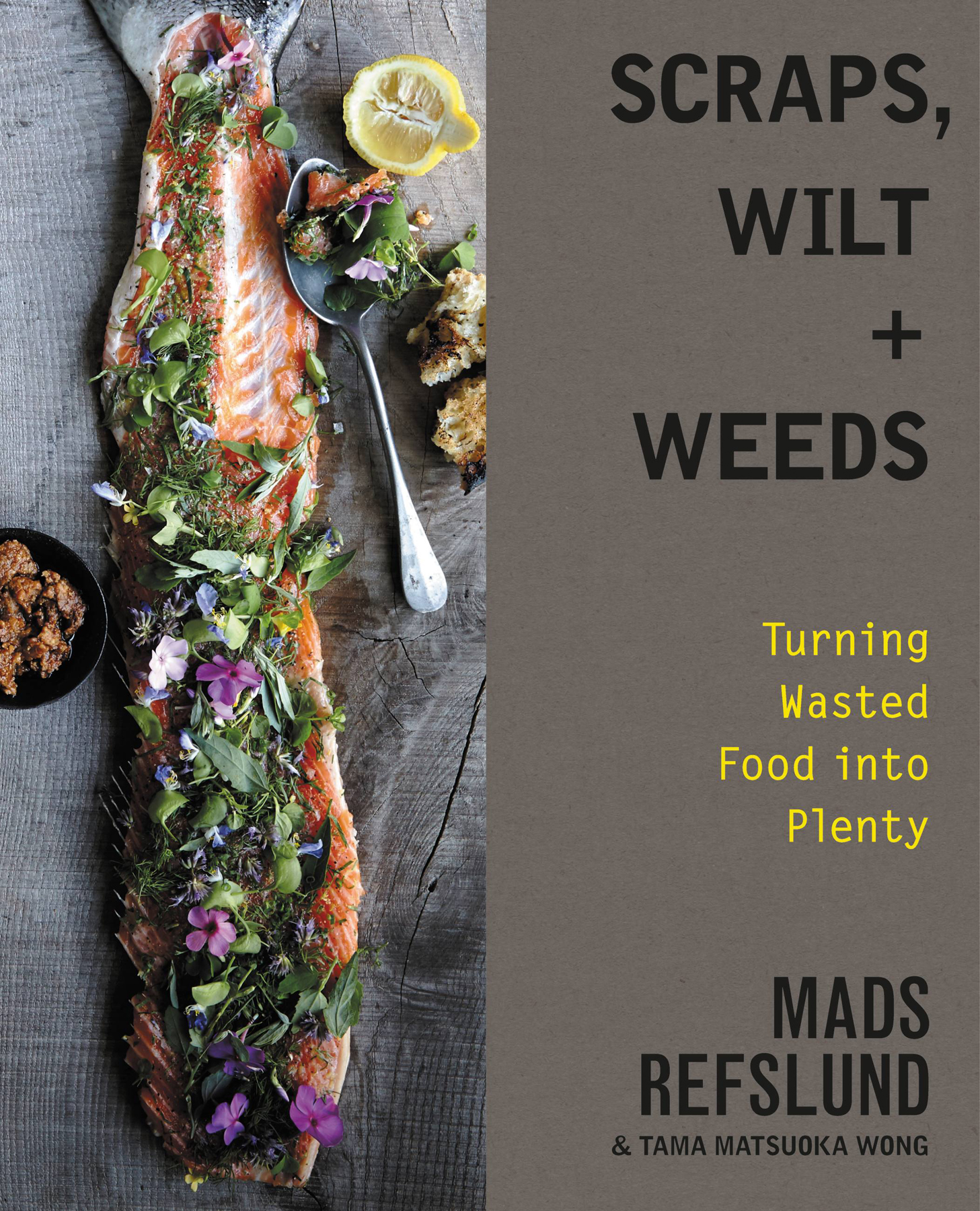

I HAVE HEARD THAT the United Nations rated Danes number one in happiness, but in terms of money, the Danish economy doesnt come even close to the top ten. How can people feel happy through such bleak winters? I think Danes do worry a lot, but they have a long tradition of resilience, of making plenty out of nothing, with little more than our own labor and the human spirit of creativity.

We celebrate the beauty of food from nature, like so many other cultures of the world. We cant grow food for many months of the year, so we are forced to rely on crafting methods to survive well, through the dark times: fermentation, brining, drying, curing. It is normal to eat all parts and scraps, wasting little. So maybe its more about a way of life that makes people feel rich, turning garbage into gold.

But of course we now live in a globalized world with its lure of luxurious and exotic ingredients: spices like harissa and saffron; truffles; tropical fruitsall from faraway places with less harsh climates than ours. Everyone always wants to get their hands on these things, but not me.

When I was at culinary school in Copenhagen, the day would begin with a cart full of ingredients to cook from. I would wait for the other chefs to pick first. I waited to see what they would grab, because I wanted to take the things left at the bottomforsaken because they were ugly or took too long to cook. I wanted to make them delicious, and to honor them: beautiful gifts from nature. Others would choose the prime rib or langoustine. I would choose the root vegetables.

Because after all what is good food and what is trash? Trash and scraps are ideas that people create when they decide what is in and what is out. Civilized cultures decide what is luxury and what is rubbish. Who made these rules?

Instead I am inspired by natures rules. In nature, there is no ugly, no trash, just cycles of change. Good food must embrace nature. A beautiful ingredient is unique, each plant a little bit different, not perfect as if it were produced in a factory. I found that I wanted to work with honest ingredients, with what I see and touch in front of me. Unlike overprocessed food, meals with ingredients that are closer to nature are alive with flavor notes and nuances.

I came to America from Copenhagen less than five years ago. I fell in love with the city and a girl and decided to move here, to New York City. New York is different from Copenhagen. New York is a city packed with 20 million people instead of 2 million: exciting and diverse people and food from all over the world. Even when I decided that I would get only local products, I found the markets were full of a vegetable and fruit bounty I only dreamed of in Denmark.

But even with all these great choices, I find it funny that many Americans across the country still pretty much eat the same kinds of foods, from four plants: rice, wheat, corn, and soybeans.

And many people eat their meals in a kind of automated way, the same twenty-five produce items over and over, like living in a self-imposed Danish winter. I wanted to try new things, like the native pawpaw fruit or the spicebush berry. Why do the people living here not care about their own native fruits or the trees around them? Why do people not eat salmon with the skin on or have a hunk of cauliflower at the center of the plate? Why does a dessert have to be a cake with lots of artificial icing instead of using the natural sweetness of beets or wheatgrass? I didnt want to just play it safe and make a stereotypical version of burgers and fries, pizza, or some kind of heavy sauce around a pork chop. I wanted juicy, refreshing, and light meals with great flavor.

And there is a lot of great flavor in the food that people threw out: in garbage bags with uneaten food piled up on the sidewalks, in markets, kitchens, dumpsters, trash bins, and even on docks and farms. I didnt get turned off by the grittiness, the garbage. I saw an opportunity. I started getting really excited about bringing the philosophies that began for me in Denmark to my new home in America. I also liked the downtown casual lifestyle. Some of the best meals Ive eaten are simple and clean, layered with flavor and conversation. Its the spirit of what we call hygge: coziness, meaning good living.

When I was young, in Denmark, my parents took time off from work for a few years, and we lived on an island. It was kind of a farm. They had a vision and created a home-stay program, sponsored by the Danish government. Their idea was to create an oasis to help people with troubles get better through nature, food, and a place to stay. There is a kind of poetry about that kind of life, so close to the outdoors. I still see it today in the shapes and textures of vegetables, fruit, fish, and meat as they are made, whole in the outdoors, not decapitated and made pretty for consumers.

I seek nature in food, by cooking and serving it on the plate. I always start by wanting to see what the produce is like whole, the way it was living in nature. Yes, with dirt and guts and tough parts. Each of these parts is important and has a role in the life of that species and is beautiful in its own way. Using all the parts is a way of respecting the plant, the fish, the animal, and its life. Of course, you have to set aside the parts that have poisons, such as apple seeds, but there are ways to tenderize the tough, to puree the wilted, and make the most of the basic character of a native plant or animal. Look at their strengths, not their weaknesses. They may still have a beautiful color, even if misshapen. Their shriveled structure may mean they are already on their way to becoming dried.