The Big Marsh

The Big Marsh

The Story of a Lost Landscape

Cheri Register

Text 2016 by Cheri Register. Other materials 2016 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 551021906.

www.mnhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-0-87351-995-3 (paper)

ISBN: 978-0-87351-996-0 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

This and other Minnesota Historical Society Press books are available from popular e-book vendors.

And yet with all these growing signs of prosperity I realized that something sweet and splendid was dying out of the prairie. The whistling pigeons, the wailing plover, the migrating ducks and geese, the soaring cranes, the shadowy wolves, the wary foxes, all the untamed things were passing, vanishing with the blue-joint grass, the dainty wild rose and the tiger-lilys flaming torch. Settlement was complete.

Hamlin Garland, A Son of the Middle Border , 1917

As conquerors and as gardeners we came to a landscape with serious intentions: not simply to know, but to change; not just to visit, but to possess. Much that was done was good, much was bad. We presumed too much. We imposed on what we found; we could not cherish without embellishing or altering what was simply there.

Gretel Ehrlich, Surrender to the Landscape, Harpers Magazine , September 1987

The Big Marsh

Prologue

The grass is wildnot the kind my dad seeds and mows in the yard. It reaches all the way up my short legs, brushes my waist with wispy plumes, and hides me if I squat. It tickles and itches, squeaks between the palms of my hands, and can cut me if Im not careful. Spiky balls of pinkish purple peek up like polka dots through the grass, come loose in my fingers, and ooze sweetness between my teeth. Down a steep bank near the edge of the highway, mud squishes between my toes. My cheeks tingle with droplets of moist air. I can see across the highway and across a field sometimes covered with bales of hay to the slough, where frogs chirp and cattails rise in clumps. I know the cattails feel, like the velvety cloth on a chair, and I want to touch them, but I cant go there. The highway is my boundary. I wait and look and listen. The sounds are comforting, the music of spring and summer, of freedomno coat, no snow pants, no shoes. Two birds call to me: one sings a melody; the other trills the same line again and again. They will forever be the sounds of home. Above me, in a dome of sunlit blue sky, puffy white clouds like mashed potatoes float on a single plane. This is my earliest sensory memory.

A girl from long ago stands in the uncut grass beside her fathers smithy. She has been promised many times that the papa she barely recalls will ride up someday on his new horse when the war is over and the cavalry comes home. Its a hard word to saycabalry. She practices touching her lip with her teeth the way big sister Marietta has taught her. Papa will fire up his forge again and teach George and DeWitt the blacksmith trade. The dome of Amanda Speers world is a hazy blue. She tips her face up toward the white and shadowed shapes that float overhead. A breeze flits across the Big Marsh and picks up a pleasant watery chill. Out in the pasture where the animals graze, a bird her mother calls a meadowlark sings its pretty melody. Up the creek where the marsh fans out, birds with red patches on their wings trill their tune from cattail perches.

A few miles and years away, a ten-year-old lopes through fields and meadows, cutting through grass that sometimes reaches boy high. He wants to catch the exact moment when the marsh sounds take overthe quacks and honks, the constant chorus of peepers, the konkaree of the red-winged blackbird that sends waves of joy through his chest. The watery world beckons him, and he delights in the moist air, the shimmering sunlight, the pattern of clouds overhead, the gleam of water stretched out before him. The sounds and sensations produce words and rhythms in his mind, the poems that will help him preserve these moments. Each year of his youth, Elbert Ostrander ventures farther, until he reaches the eastern shore of the big lake at the north end of the marsh, where he finds black walnut trees, flowering alder shrubs, shore willows, pigeon cherries, wild lilies, and irises of royal blue. He returns again and again to climb on and lie under the arch of the mysterious oak that bent over and grew back into the ground. In his later years, he will recall Geneva Lake as the lake of my childhood dreams, the embodiment of an Eden, a Paradise.

Here in our contiguous Edens, we are finding beauty. We have no mountains to teach us grandeur, no roaring ocean surf to fill us with awe. We learn to love subtlety: the iridescence of a dragonfly, the bronze and copper hues of November, the brief blue twilight of a midwinter morning, the swish of a muskrats tail rippling still water, the crunch of acorn caps underfoot. We are Midwesterners making ourselves at home.

PART I

The Lay of the Land

Hollandale: An Introduction

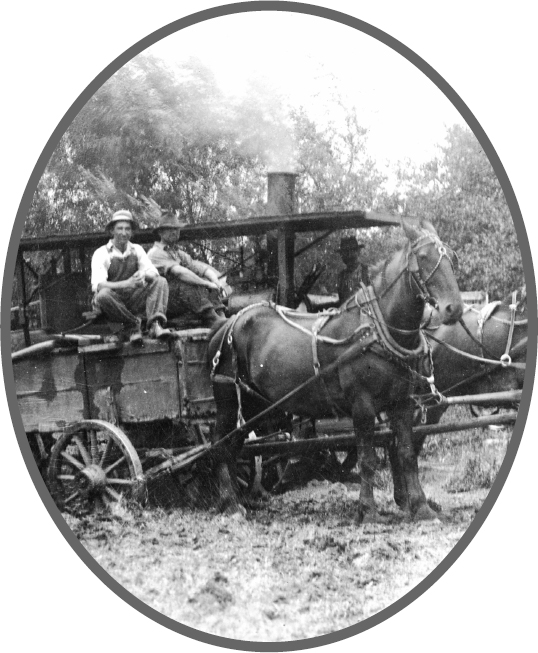

There was a timean eon of timewhen water pooled and ribboned freely among the oak savanna and hardwood copses and in the prairie potholes of southern Minnesota. Crops grow there now, on dry land that might yet hold water in its low spots after a heavy, heavy rain. The absence of the old wetlands is to some a tale of triumph: agricultures conquest over waste and wild to feed a hungry humanity. To others it is a doomsday story of irreversible damage to the natural environment. We Minnesotans like to think of our state as natural, and it is often colored a lovely deep green on the US map. Yet the original landscape has been radically altered in less than two centuries of European settlement, not least by the miles of drainage ditches that crisscross the farmland and the even lengthier grid of hollow clay and concrete tiles and plastic piping buried beneath its soil. Freeborn County alone, now with 340 miles of ditches, had lost 98.5 percent of its wetlands by 1981.

Many people dont know this subterranean network of field drains exists until, for example, a flood brings to light the risks of draining a heavy spring thaw or torrential rains into an already overburdened river. Alarms are sounding about the polluting effect of farm runoffsoil, fertilizers, and pesticideson lakes and rivers, especially the Minnesota, which empties into the Mississippi, clogging Lake Pepin with sediment and nitrates and contributing to the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico. Yet the states farmers face continuing economic pressure to drain and cultivate more land.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.