Geographies of Disorientation

Spatial disorientation is of key relevance to our globalized world, eliciting complex questions about our relationship with technology and the last remaining vestiges of our animal nature. Viewed more broadly, disorientation is a profoundly geographical theme that concerns our relationship with space, places, the body, emotions, and time, as well as being a powerful and frequently recurring metaphor in art, philosophy, and literature.

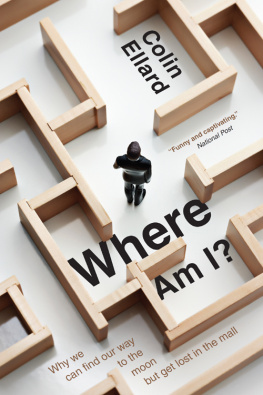

Using multiple perspectives, lenses, methodological tools, and scales, Geographies of Disorientation addresses questions such as: How do we orient ourselves? What are the cognitive and cultural instruments that we use to move through space? Why do we get lost? Two main threads run through the book: getting lost as a practice, explored within a post-phenomenological framework in relation to direct and indirect observation, wayfinding performances, and the various methods and tools used to find our position in space; and disorientation as a metaphor for the contemporary era, used in a broad range of contexts to express the difficulty of finding points of reference in the world we live in.

Drawing on a wide range of literature, Geographies of Disorientation is a highly original and intriguing read which will be of interest to scholars of human geography, philosophy, sociology, anthropology, cognitive science, information technology, and the communication sciences.

Marcella Schmidt di Friedberg is Professor of Geography at the Riccardo Massa Department of Human Sciences and Education at the University of MilanoBicocca, Italy. Her research interests include cultural geography, island studies, gender geography, and the history of geographical thought. She is a member of the Editorial Board of ACME and Chair of the IGU Commission on the History of Geography.

First published 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2018 Marcella Schmidt di Friedberg

The right of Marcella Schmidt di Friedberg to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-1-4724-5048-7 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-58468-3 (ebk)

For Alfi, who never gets lost

This book is the outcome of many years of wandering through the meanders of a theme that I consider to be of the utmost importance. I am particularly grateful to Claude Raffestin for having encouraged and advised me along the way, and for sharing my passion for the labyrinth. I thank Guido Scarabottolo for granting me permission to reproduce his drawing on the theme of getting lost. Several scholars contributed valuable feedback on draft versions of chapters and chapter sections: amongst others, Claudio Smiraglia, Gnther Seufert, Enrico Squarcina, Giuseppe Iaria, and Augusto Lovagnini Scher. The Riccardo Massa Human Sciences and Education Department at Milano-Bicocca University provided financial support enabling the timely completion and translation of this work. I am also indebted to Kathy Crossan and the editorial team at Routledge for believing in this project and its publication. I thank Clare O Sullivan for her scrupulous and thoughtful translation, and my masters and doctoral students in Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences and Social and Cultural Anthropology, respectively, for sharing their insights with me in the course of lengthy discussions on the theme of disorientation. I would also acknowledge the use of extracts of the following publications with grateful thanks: John O'Keefe and Lynn Nadel (1978), The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map, originally published by Oxford University Press, by permission of the authors; Sara Ahmed (2006), Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, by permission of Duke University Press; Mark Monmonnier (1991), How to Lie with Maps, by permission of University of Chicago Press; Allen W. Wood, Kantian Ethics (2008), by permission of Cambridge University Press; Paul A. Dudchenko (2010), Why People Get Lost: The Psychology and Neuroscience of Spatial Cognition, by permission of Oxford University Press; Reginald G. Golledge, ed. (1998), Wayfinding Behavior: Cognitive Mapping and Other Spatial Processes, by permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

I am grateful to my daughters, Caterina and Margherita, for their moral support and for sharing with me the joy of getting lost. Finally, disorientation is such a broad theme that I owe thanks to many more people colleagues, friends, and students (Elena dellAgnese, Cristina Schmidt, Marie-Clare Robic, Marjorie Hedges, Silvia Lista, Valeria Pecorelli, Mario Neve, Stefano Malatesta, Margit Schreiner, Pia Antonini, Karine Douplitzky, Marco Benedetti, Aylie Lonmon, Fabio Castelli, Rossella Giraudi, Giorgio Mosterts, Anna di Seyssel, and numerous others), who often via a single comment or reading recommendation opened my eyes to a whole new dimension of disorientation.

Note: The English translation of the text, including citations from the foreign-language sources listed in the bibliography, is by Clare O'Sullivan.

Claude Raffestin

Our choices almost invariably conceal an enigma, for ourselves in the first instance and for others thereafter. Why did we choose to do this rather than that? In most cases, the question is of greater import than the answer, because the question is the very foundation on which knowledge is built. Over time, answers may vary, but the questions will remain the same.

Why has a geographer developed an interest in I might say a passion for the labyrinth? Claiming that the answer is less important than the question exonerates me from seeking out or imagining all the reasons behind Marcellas decision to grapple with the labyrinth; in reality, however, it was the labyrinth that grabbed hold of her though happily she has managed to avoid being devoured by the Minotaur!

Oh, how well I understand this passion of Marcellas for the labyrinth, which concentrates and crystallizes the essence, if not the entirety, of all questions of space and time. For what is the labyrinth if not a symbolic microcosm which at once comprehends both the material place of a relational system, woven among multiple actors of shifting morphologies whose limits attest to their existence, and the immaterial place of a set of great myths that have been incessantly revisited, reworked and reinterpreted throughout history? A symbolism that is amply illustrated in this book, to which no foreword can have anything to add. As so aptly observed by Borges: a preface, when favoured by the stars, is not in the manner of a toast; it is a lateral form of criticism. Thus, I draw on lateral thinking here in order to throw into relief what might be concealed at first view, rather than to eclipse this volumes evident riches.