All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

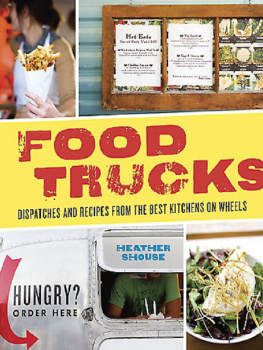

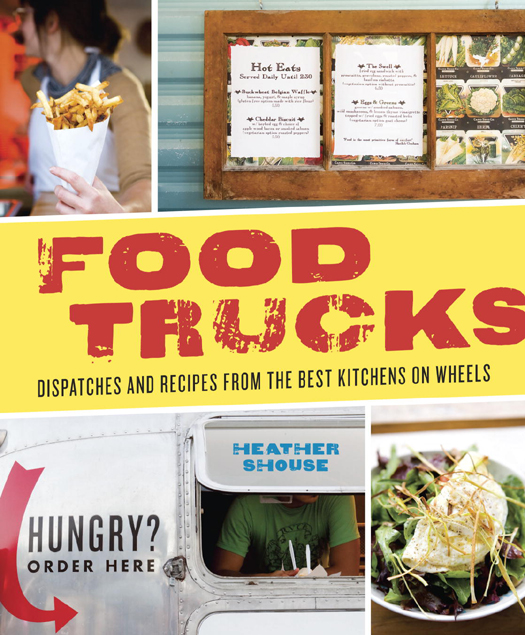

T hanks to Alexandra Sheckler for being the best research assistant I could have asked for; to my agent Jane Dystel for believing in my talents; to my editor Melissa Moore for her patience and persistence; to my designer Betsy Stromberg for building a beautiful book; to Leo Gong for his amazing photos; to Sarah Watts for maps that would make Rand McNally jealous; and to all of the truck, cart, and trailer owners for letting me into their lives for a bit. And above all, thanks to Mom and Dad, for everything.

INTRODUCTION

F orget everything you think you know about food trucks. During a year of traveling the country researching the topic, I stumbled upon a few truths: gleaming mobile kitchens run by trained chefs who have mastered Twitter can turn out disastrous food. Rickety carts with questionable permits might just turn out some of the best. The roach coach moniker doesnt apply to the majority of this countrys mobile food operations any more than it does to the majority of this countrys restaurants (well, save for the coach part, of course). And no, Kogi did not invent the food truck. But they just might have reinvented its wheels.

At least they got the world to sit up and take notice. The L.A.-based Korean taco truck was repeatedly cited as a source of inspiration by food truck owners I spoke to during my travels, and in the time since Kogi rolled out in late 2008, the buzz around food trucks has reached fever pitch. Favoring quirk over pomp, talented cooks and critically acclaimed chefs are ditching the brick-and-mortar standard for kitchens on wheels, churning out incredible food for a new breed of diners more interested in flavor than fuss. Just in time for the biggest recession this country has seen since the Depression, this alternative to the traditional restaurant model proved to be a pretty smart business move for many talented cooks. What with rent or mortgage, tables and chairs, dcor, front-of-the-house staff, a stocked bar, and additional labor, the average restaurant costs around $400,000 just to get the doors open. Most of the food truck owners I met across the country spent a fraction of that, more in the neighborhood of $20,000 to $50,000 to get up and running. Sure, theres the disparity in profits to consider, but for the most part these truck chefs are still making a decent living, while reaping the benefits of being their own boss and creating the biggest buzz the industry has seen since the advent of quick-serves.

In fact, the interest in food trucks has become so widespread that in September of 2010 Business.gov, the U.S. governments official website for small businesses, added a page titled Tips for Starting Your Own Street Food Business, with links to state departments of health, zoning laws, and business permits. Navigating the red tape is often cited as the biggest hurdle for wanna-be food truck operators, so many of whom are itching to get into the game that several cities are being forced to reexamine their mobile food vending laws to satisfy the growing demand. Cities such as Los Angeles, where food trucks have long been legal, have seen mobile food vendor applications quadruple in the past two years, along with complaints from restaurants facing new competition. In response, city council panels have been set up specifically to keep the peace, setting limits on the number of permits issued and establishing new regulations on a continual basis. In areas where street food vending has historically been something of a nonissue, the city governments are scrambling to come up with regulations, as well as decide exactly where they stand on the issue. Case in point, Boston mayor Thomas Menino: to get his city up to speed with his neighbors to the south, New York and Philly, he hired a new food policy director in 2010 and launched a Food Truck Challenge to test the waters, with a goal of permitting thirty to fifty trucks by summer of 2011. Similarly, in June of 2010, Cincinnati approved a Mobile Food & Beverage Truck Vending Pilot Program to create twenty designated food truck parking spots in the downtown area; within a month all twenty slots were filled.

Keeping up with the regulation changes, the cities jumping on board with the movement, and the cities slow to come around (looking at you, Chicago) is as dizzying as tracking each new arena the popularity of food trucks seeps into. For the fall season of 2010, Food Network launched the show The Great Food Truck Race, a sort of street food take on the Amazing Race. On user-generated sites like Yelp, beloved trucks from various cities are holding their own with big-name restaurants. The annual National Restaurant Association convention (the biggest show in the industry) now has a section of the showroom floor dedicated solely to food trucks, with equipment companies, graphics specialists, and truck manufacturers chomping at the bit to sell their services to the next Kogi. Needless to say, these mobile kitchens have come a long way since the chuck wagons of the Wild West, the construction-site lunch wagons of the mid-1900s, and even the taco trucks that started popping up throughout the country in the 1970s. Taking many formsa custom-welded pig-shaped rig complete with giant snout, a gleaming carnival on wheels manned by a crew sporting fake moustaches and turbansthis new breed of food truck often stakes out regular spots to set up shop for the day, but more recently, with the advent of Twitter, legions of chowhounds are kept in the loop with updates of the trucks travels.