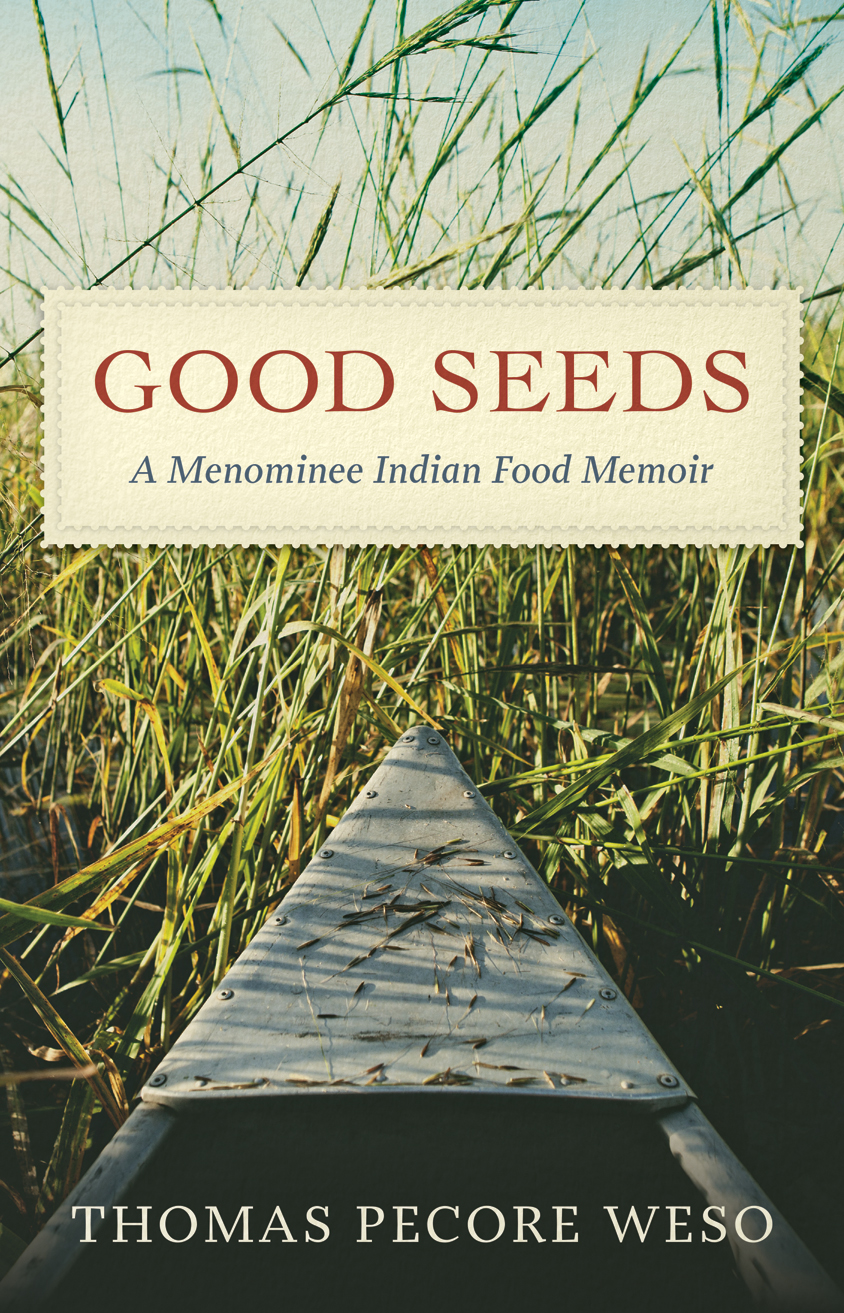

Good Seeds

Whenever the Menomini enter a region, the wild rice spreads ahead; whenever they leave it the wild rice passes. (Elder, quoted in Keesing, 1939)

Good Seeds

A Menominee Indian Food Memoir

Thomas Pecore Weso

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

The Wisconsin Historical Society helps people connect to the past by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories. Founded in 1846, the Society is one of the nations finest historical institutions.

wisconsin history .org

Order books by phone toll free: (888) 999-1669 Order books online: shop.wisconsinhistory.org

Join the Wisconsin Historical Society: wisconsinhistory.org/membership

2016 by Thomas Pecore Weso

E-book edition 2016

The following pieces first appeared in a slightly different format in the following:

Fire: Grandmothers Morning, in Native Literatures: Generations 1, no. 3 (Fall 2010), http://www.nai.msu.edu/resources_for_tribes_and_american_indian_organizations/publication/native_literatures_generations.

Prayer: Grandfathers Dreaming, in The Muckleshoot Review 3 (2011): 7074.

Partridges excerpt and Greens excerpt published in Heid Erdrichs Original Local: Indigenous Foods, Stories, and Recipes from the Upper Midwest (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2013).

German Beer, first published as Death on the Reservation in Show + Tell: A Celebration of Art, an Expression of Word (Kansas City, MO: Potpourri and Kansas City Artists Coalition): 141143. Reprinted in Yellow Medicine Review (Spring 2011): 4450.

For permission to reuse material from Good Seeds (ISBN 978-0-87020-771-6; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-772-3), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

Many of the recipes in this book call for ingredients that were traditionally used as food. However, proper identification and preparation of these ingredients is the responsibility of the reader. Neither the author nor the publisher shall be responsible for any loss, injury, or damage resulting from information included here.

Designed by Percolator Graphic Design

201918171612345

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for.

To my wife, Denise,

and to our children, PEmecewan, Daniel, David, and Diane

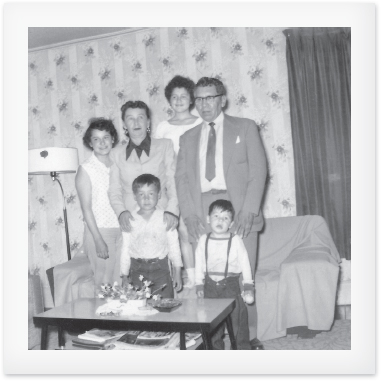

In the back row, from left, are my mother, Frances (Weso) Walker; my grandmother Jennie (Heath) Weso; my aunt Lorraine (Weso) Smith; and my grandfather Moon Weso. In the front row, my older brother Gerald stands on the left and I am on the right. FROM THE AUTHORS COLLECTION

Contents

My Grandfather Moon was considered a medicine man. His morning prayers were the foundation for each days meals. This is how I understand cooking, as part of a family process that includes spirit, the forest environment, and fuel for cookingall before the meal can be prepared. In the kitchen, my grandmother Jennie made fire in a traditional way every morning before dawn in a wood-burning stove. She woke her sons to go out hunting or fishing, depending on the season. As I grew up, my uncles taught me to hunt bear, deer, squirrels, raccoons, and even skunks for the daily larder. Grandma oversaw huge breakfasts of wild game, fish, and fruit pies. She organized her daughters into effective teams for both meals and the family business of food stands.

Grandmother Jane (Heath) Weso, known as Jennie, lived from 1911 to 1979, and Grandfather Monroe Weso, known as Kaso (Moon), lived from 1904 to 1983. They attended assimilationist boarding schools where they learned about the dietary culture of the larger United States. Their lives spanned the early-twentieth-century development of the logging industry, termination of the Menominee Tribe in 1958, and restoration of the tribe in 1973. They saw the rise of legal, religious, and educational rights for Native peoples. Six children, many grandchildren, and several generations of great-grandchildren descend directly from this couple.

The culinary experience of my grandparents large household left vivid memories. I remember the excitement of sugar bush, maple sugar gatherings that included dances as well as hard work. I remember our familys food stand at the Menominee County Fair and yearly powwow, where my grandmothers meat pies and baked beans were a favorite.

My grandparents shared many foods with their northern Wisconsin European settler neighbors. They also perpetuated ancient hunting, gathering, farming, and storage practices from the earliest Algonquin woodland dwellers. Jennie and Moon Weso were an important link to the food knowledge of the earliest times. They also modeled an integral aspect of Indigenous survivaladaptation to new conditions. The most basic element of survival is food, and the open attitude toward all kinds of food has been an important asset for the Menominee people.

Following my family tradition, I attended Haskell Indian Nations University, where my grandfather attended in the 1910s and then my mother, aunts, and uncles attended in the 1940s and 1950s. My daughter received a degree from Haskell also. In 1994 I received an associate of arts degree, and from there I continued my education at the University of Kansas. I received both an undergraduate degree in anthropology and a masters degree in global Indigenous nations studies. By then, I had married a Kansan and settled in the river town of Lawrence, less than an hour from Kansas City. Mild winters are a luxury, and hot, dry summers are a penance. In Lawrence, I learned the rich food traditions of the lower Midwest, including barbeque, comfort food, Southwest spices, and bison. Cooking interests me, especially the cultural context for food usage. As I told stories about Menominee cooking to my wife, she encouraged me to write them down. This book is the result of several years of stories, added gradually. My wife, Denise Low, is a writer and helped me with editing suggestions and organization.

My appreciation goes to all my family who helped with this book with encouragement and many great meals. Thank you to Frances (Weso) Walker, Bobby and Nita (Weso) Perez, Mary Walker-Sanapaw, Donovan Walker, Terri Katchenago, Gerald Weso, Morgan Buttner, Laura Paredes, Rachel Corn, Yvonne Katchenago, and Monroe Weso. Aunt Nita Perezs help with newspaper archives is also appreciated.

As I pass sixty years of age, I appreciate more fully the strength of the generations before me. I hope this collection helps to preserve the rich food culture of the Menominees and of all Indigenous peoples. My grandparents were important figures throughout my life. This book is an attempt to explain their legacy.

The Menomini wife is allowed a rather wide latitude of choice in her activities. She may leave her children with a grandmother and accompany her husband on fishing and hunting trips and help him with housebuilding and the gathering of ferns, or she may choose to remain close to her home and children, performing the more conventional tasks of child-care, cooking, tanning, washing clothes, and sewing. (Louise S. Spindler, Menomini Women and Culture Change, 1962)

If I were not farming, I should make mats and quilts and beadwork, and I should go to Neopit to do washing, so as to earn money. I should sell all the mats. Baskets too I should make. When I had made a great quantity, I should sell them all. From this I should obtain much money.... I should always gather raspberries and sell them. That is what I should do, if I did not farm. (How a Menomini Woman Earns Money Maskwawanahkwatok, in Bloomfield, Menominee Texts, 1928)