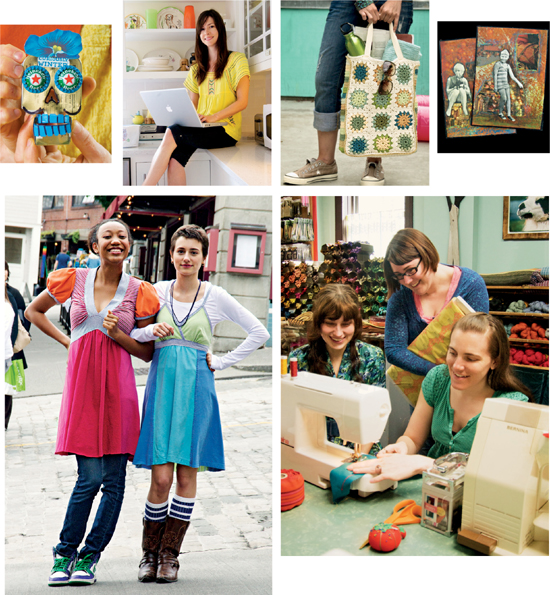

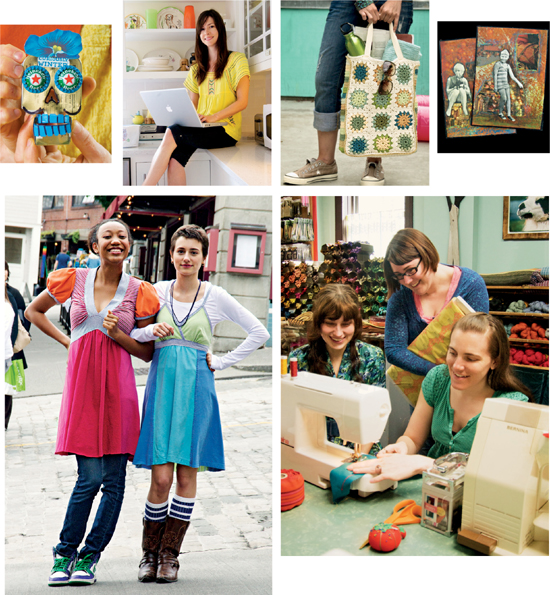

Showing a flair for fashion, a model in the Tongue-in-Chic Skirt turns the head of ukulele busker Howlin Hobbit on the streets of Seattle.

When I am asked to define craft, I dont and I wont. I like to think of it as undefinablewith no rulesand that is why I was drawn to it in the first place. Craft is a way to connect with people, a way to create a community that you are inspired by. I have come to realize that once ones hands are in motion, making is difficult to stop. There may be long lapses, unfinished projects, even disasters, but the feeling inside you never leaves. Do you know the feeling I am talking about? The one that makes you relax, focus, and feel proud that you are making something? That is an example of the power of craft. Regardless of ones skill level, I truly believe that making things makes good.

While conducting interviews over the past few years, I must have asked hundreds of people the same question: So, how long have you been making stuff? Ask me, and my answer, like many of yours, is Ive always made things, ever since I was a little kid.

What I make now is films, and what I have made in the past runs the gamut of craft. My story would continue: No, I didnt go to college. Yes, I make a living as an independent artist. No, Im not professionally trained. No, I dont currently have to support kids or pets. Yes, its difficult to balance it all. Yes, I work all the time. And yes, I am very, very happy with my life.

But that story is mine. The story of the girl next to me will be very different. So, too, the story of the guy next to her, and so on. That is what I love about this book: We get to see into the lives of others, to understand what motivates them. We all live very differently under the umbrella of craft, though we share a common bond of making and creating. Its who we are and will continue to be, as we grow old. Then another generation will come along and start it all over again. Or so we hope.

Living a DIY lifestyle is nothing new. Our generations interest in the resurgence of craft started as a grassroots phenomenon, though now I think its safe to say its leaked into mainstream culture. We make to provide. We make to give. We make to share. We make because we love. Making is marketable, its green, its local. And when the fad passes, we will still be making. Because making things by hand has never stopped, and it will never disappear.

When it comes to craft, I encourage you all to spend time observing and absorbing whats around youin your personal lives and also what is available online. Be inspired by the amazing people and projects within this book. Make the ideas your own, use the resources as a springboard, and then share your story with others. Remember, the empowerment of craft is contagious.

In 2008, I happened to visit La Connor, Washington, a small, artsy community with several museums, a smattering of galleries, and a healthy program of outdoor sculpture. The latter included a statue of a gone-but-not-forgotten town canine known as Dirty Biter, whose sleek bronze body was wrapped in a handcrafted sweater. The garment was the work of a drive-by knitter, I heard, who had also placed boalike scarves around the neck of Silent Words, another sculpted figure across the street. No, no one knew who the nameless needleworker was, the woman in the local yarn store told me, which may or may not have been true. But that was my first experience with knit bombingtagging trees, poles, and other public spots with knit or crocheted swatches.

Boy, was I ever intrigued. Among the questions that fascinated me (along with the obvious, Didnt anyone see the person do it?) were: Why would someone do such a thing? And how? Overall, though, my reaction was: This is a great idea and a very funny one. As I began to read about knit bombing (also known as yarn bombing), I realized that it was a worldwide movement with warm and cozy, if sometimes gargantuan, results. Knit bombers have covered a bridge in Ontario, an artist named Magda Sayeg had tagged the Great Wall of China, and statues have been seen wearing scarves from Europe to Australia, prompting me to wonder, how is it that knitting has emerged from ones sitting room onto a broader stage?

Later I came to realize that all kinds of crafts have moved from personal passion to public statement. Think of the impact the AIDS quilt has made over the last twenty-five years. More recently, makers have come up with all kinds of clever ideas to be eco-friendly, including reusable bagsmade of fabric, recycled plastic, and yarn, to name just a fewas part of an energetic campaign to do away with the ubiquitous plastic grocery bag.

As photographer Gale Zucker and I met and talked to crafters, many of whom are featured in this book, we were stunned to realize how far-reaching this new blend of craft and activismwhat writer Betsy Greer has called craftivismreally is. It affects what people make, why they make it, what they make it out of, and whom they tell about it. Its part of the DIY movement, which promotes handmade objects (and a lifestyle that goes with them) over mass-produced articles. And the work as been enriched by formally trained artists who are embracing age-old crafts. The irony, of course, is that the new directions, popularity, and even profitability of the work of ones own hands and heart have been expanded by the most up-to-date technology, in particular, by the Internet.