Food in the Philippines

Islands with a history of colonization nourished a people with a gift for adaptation

by Doreen G. Fernandez

What is Filipino food? Is it adobo which has a Spanish name, yet contains chicken, pork, vegetables or even seafood stewed in vinegar and garlic, and is thus unlike any Spanish adobado? Or is it pancit noodles of many persuasions utilizing local ingredients, yet obviously of Chinese origin? Or would it be sinigang the sour broth related to similar Southeast Asian soups and stews that are cooling in the hot tropical weather? Could it even be the omnipresent fried chicken sometimes marinated in vinegar and garlic before it is fried? Or arroz caldo a chicken congee that is served as comfort food even on airlines?

The land and the waters provide the Filipinos with an abundance of tasty and nutritious food ingredients. Seven thousand and more islands are surrounded by seas, watered by rivers and brooks, bordered by swamps and dotted with lakes, canals, ponds and lagoons, providing a multitude of fish and other water creatures that make up the basic diet of Filipinos. This variegated landscape of mountains and plains, shores and forests, fields and hills is inhabited by land and air creatures that generously transform into food. It also brings forth greenery all year-round, a garden of edible grains, leaves, roots, fruits, pods, seeds, tendrils and flowers.

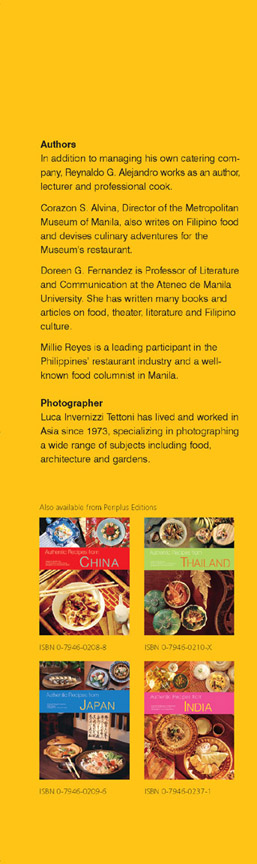

ABOVE: "Fte Santa-Cruz de Nano", (1887) by Marcelle Lancelot (after Andrews). First published in LuCon et Palaouan: Six. Ann es de Voyage aux. Philippines by Alfred March. This engraving depicts Manileno ilustrados enjoying a neighborhood party. Hustrados, meaning "enlightened ones", comprised an elite urban class with a high level of education and nationalism.

Thus, the Filipino dietary pattern: rice as the staple, steamed white and plain, providing a background to the flavors of fish, meat and vegetables. It is, nutritionists judge, one of the healthiest eating patterns in the world.

Because the island geography makes food readily accessible to hunters, fishermen, food gatherers and farmers, indigenous dishes are simply prepared: grilled (inihaw), steamed (pinasingawan) or boiled (nilaga). Some dishes even require no cooking at all, as with kinilaw, fish briefly marinated in vinegar or lime juice to "cook" it, while retaining freshness and translucence.

Since food is one of the liveliest areas of popular cultural exchange, it has of course been subject to foreign influences and change. Chinese traders, the Spanish colonizers and proselytizers, and in the 20th century, the United States all left their mark on the local cuisine. The signature ingredients of Southeast Asia are present here too, in the form of chilies, lemongrass and the pungent fish sauce called patis. Recent times have seen foods from other more distant lands sometimes occupying a small corner of the Filipino table. To the question therefore, "What is Filipino food?" One can simply answer, "All of the above."

The Philippines national culture begins with a tropical clime divided into rainy and dry seasons and an archipelago with 7,000 islands. These isles contain the Cordillera mountains, Luzon's central plains, Palawan's coral reefs; seas touching the longest coastline of any nation of comparable area in the world; and a multitude of lakes, rivers, springs and brooks.

The population120 different ethnic groups and the mainstream communities of Tagalog/llocano/ Pampango/ Pangasinan and Visayan lowlanders developed within a gentle but lush environment. Each group shaped their own lifeways: building houses, weaving cloth, telling and writing stories; ornamenting and decorating, and preparing food.

Foreian influences made a deep impression on native island cultures. Chinese traders who had been coming to the islands since the 11th century brought silks and ceramics, took back products from the forest and sea, and left behind them many traditions so deeply embedded in daily life that Filipinos do not realize their provenance. Filipinos of Chinese ancestry comprise an important facet of the national profile.

In the 16th century, the Spanish colonizers imported Christianity and a dominant Iberian elite that lasted three centuries. Families were "brought within the sound of church bells"; and thus were created villages, towns and cities.

Spanish cultural forms replaced or melded with indigenous expressions. The folk cultures of the Christianized lowlands are thus greatly Hispanicized, whereas the highlands were later reached by Protestant missionaries and in southern Mindanao Islam flourished and long resisted Spanish colonization.

After the Revolution of 1889, the Battle of Manila Bay, and the pact of exchange between the US and Spain, the country became an American colony. The US-style government and educational system imported along with the popular culture made Filipinos the most "Americanized Asians", and the Philippines became one of the larger English speaking countries of the world.

This storied history and Mother Nature's largesse combined and evolved to produce Filipino food.

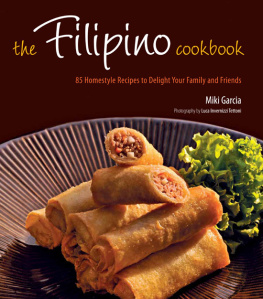

The Chinese who came to trade sometimes stayed on. Their foodways accompanied them and also stayed. Perhaps they cooked the noodles of home; certainly they used local condiments; surely they taught their Filipino wives their dishes, and thus Filipino-Chinese food came to be. The names identify them: pancit (Hokkien for something quickly cooked) are noodles; lumpia are vegetables rolled in edible wrappers; siopao are steamed, filled buns; siomai are dumplings.

All, of course, became indigenized Filipinized by their ingredients and by local tastes. Today, for example, Pancit Malabon has oysters and squid, since Malabon is a fishing center; and Pancit Marilao is sprinkled with rice crisps, because Marilao lies within the Luzon rice bowl.

When restaurants were established in the 19th century, Chinese food became a staple of the pansiterias, with the food given Spanish names for the ease of the clientele: thus comida China (Chinese food) includes arroz caldo (rice and chicken gruel); and morisqueta tostada (fried rice).

When the Spaniards arrived, the food influences they brought were from both Spain and Mexico, as it was through the vice royalty of Mexico that the Philippines were governed. This meant the production of food for an elite, including many dishes for which ingredients were not locally available.

Spanish Filipino food had new flavors and ingredients olive oil, paprika, saffron, ham, cheese, cured sausages and new names. Paella, the dish cooked in the fields by Spanish workers, came to be a festive dish combining pork, chicken, seafood, ham, sausages and vegetables, a luxurious mix of the local and the foreign. Relleno, the process of stuffing festive capons and turkeys for Christmas, was applied to chickens, and even to bangus, the silvery milkfish. Christmas, a new feast for Filipinos that coincided with the rice harvest, featured not only the myriad of native rice cakes, but also ensaymadas (brioche-like cakes buttered, sugared and sprinkled with cheese) to dip in hot thick chocolate, and the apples, oranges, chestnuts and walnuts of European Christmases. Even the Mexican corn

Next page