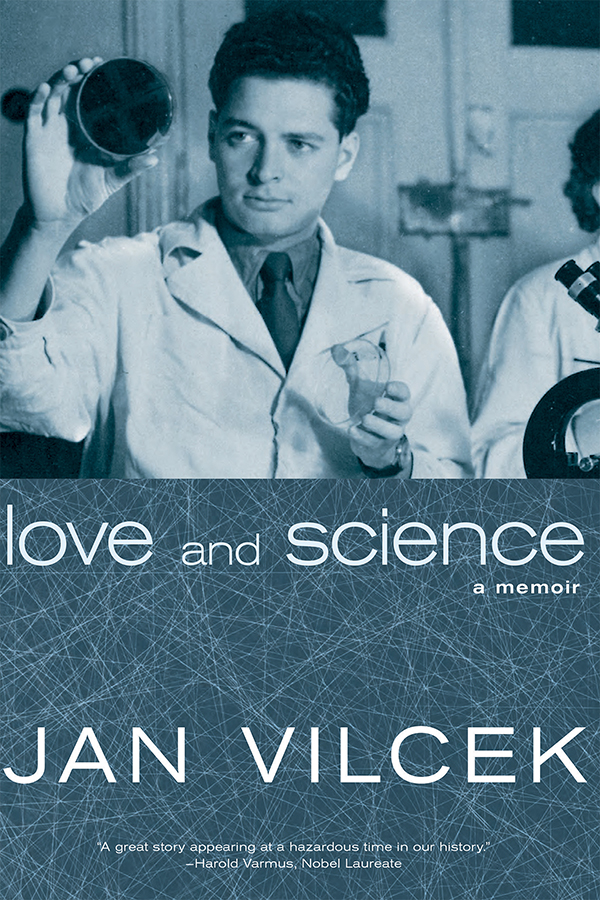

love and science

a memoir

JAN VILCEK

Seven Stories Press

NEW YORK OAKLAND

Copyright 2016 by Jan Vilcek

A SEVEN STORIES PRESS FIRST EDITION

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the

publisher.

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

sevenstories.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vilcek, J., 1933, author.

Love and science : a memoir / Jan Vilcek.--First edition.

p.; cm.

ISBN 978-1-60980-668-2 (hardback)

I. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Vilcek, J., 1933-2. Physicians--Slovakia--Personal Narratives. 3.

Physicians--United States--Personal Narratives. 4. Microbiology--Slovakia--Personal

Narratives. 5. Microbiology--United States--Personal Narratives. WZ 100]

R154.B623

610.92--dc23

[B]

2015025051

Printed in the United States of America

987654321

How great the merit, and the bliss how sweet,

When in fond union love and science meet.

Independent Gazetteer (Philadelphia), April 24, 1790

Contents

| PART ONE |  | The Wonder

of Science |

Chapter One

The Cure for Cancer that Wasnt

Scientists love abbreviations and acronyms. What better way to peacock ones expertise than by mystifying others with your areas secret codes? When I go to a lecture given by a scientist working in a field different from my own I often get lost among the acronyms. And we immunologists are as afflicted with this tendency as anyone.

IFN is the abbreviation for interferona family of natural proteins produced in an organism, usually in response to an infection. First identified in the late 1950s by the London-based British virologist Alick Isaacs and his Swiss colleague Jean Lindenmann, interferons play important roles in the defense against viruses and other infectious agents, and in the regulation of immune functions.

TNFwhich stands for tumor necrosis factorwas identified by Lloyd Old and his colleagues at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City in the mid-1970s as a protein produced in experimental animals injected with bacteria or bacterial components. The name derives from the observation that the factor appeared to cause the death of tumor tissues, or, put more scientifically, to produce tumor necrosis.

The work that led to the identification of TNF was an outgrowth of older studies showing that bacterial infections in humans or in laboratory animals would sometimes lead to a shrinking and, in very rare cases, even complete disappearance of malignant tumors. A similar shrinking of tumors was seen in tumor-bearing experimental animals injected with low doses of toxins derived from some bacteria. However, these earlier observations left unanswered the question of whether the shrinking of tumors was a direct result of the action of the bacterial toxins or whether it was perhaps mediated by something made in the body in response to the toxins. Lloyd Olds study suggested that TNF, a protein produced mainly by white blood cells, was the mediator responsible for the regression of tumors. The implication was that TNF was part of the bodys defense system against tumors. The study also raised the prospect thatwhen isolated and properly definedthe TNF protein might one day become useful as a therapeutic agent in the fight against cancer.

I first met Lloydthen a rising star in the emerging tumor immunology fieldshortly after I had joined the NYU School of Medicine as an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology in 1965. I was intrigued by TNF from the outset because it was a natural protein produced in the body that like interferona protein I had worked on since the late 1950sappeared to have a role in the immune systems array of natural defenses.

By the mid-1970s it was becoming apparent that there existed a large number of secreted proteins that were important in the fine-tuning of the bodys immune responses. In 1974 immunologists agreed that secreted proteins whose primary function is to regulate immune responses, such as interferon and TNF, be called cytokines. The first half of the term, originating from the Greek ktos, meaning cell, was inspired by the fact that these proteins are both derived from cells and act on cells. The latter half of the wordkine, as in kineticimplies that the function of these proteins is to move the immune system into action.

A quick computer search of the published biomedical literature on PubMeda comprehensive database of the US National Library of Medicinereveals more than six hundred thousand printed scientific publications where the word cytokine has been used. I commiserate with the medical and science students who have to learn about the hundreds of cytokines that have been discovered in recent decades. Cytokines tend to be identified by acronyms (like TNF, IFN, and many others) or by the abbreviation ILfor interleukinfollowed by a serial number, starting with IL-1. At this point we are up to IL-38, but the actual number is much larger because many interleukins consist of several molecular variants.

Some years after the original publication by Lloyd Old, my interest in TNF became more tangible. In the early 1980s, we were in my NYU laboratory using cells isolated from human blood to generate a type of interferon called IFN-gamma. Soon we realized that some other unknown cytokines were produced together with IFN-gamma in the same test tubes.

The methods available for the identification of cytokines in those days were still cumbersome and relied on the use of indirect biological assays. With my colleagues Donna Stone-Wolff, Hanna Kelker, and others, we eventually established that the fluids harvested from cultures of white blood cells, which served as the source of IFN-gamma, also contained two other cytokines: one of these we identified as a protein known among immunologists as lymphotoxin, and the otherthough at the time defying definitive identificationwe suspected of being identical to TNF.

In the summer of 1982, while attending a meeting on cytokines held on the campus of Haverford College in Pennsylvania, I ran into Michael Wall, a biotechnology entrepreneur whom I had known since the late 1970s. I had first met Michael when he visited me at my NYU laboratory. He was a principal at a tissue culture supply company called Flow Laboratoriesa company he had founded but later sold. Remaining with Flow Laboratories after its sale, Michael was looking for opportunities to expand into biotechnology. He came to see me because he heard about our work with interferon and was interested in establishing a collaboration with my laboratory.

Michael, an MIT-trained electrical engineer, impressed me with his grasp of the biomedical field. We also hit it off personally. He struck me not only as a man with a passion for entrepreneurship, but also as someone who cared deeply about science, in addition to being a lively and charismatic person with wide-ranging interests. We agreed to strive to establish a collaboration. I had several subsequent meetings with him and his professional colleagues, but before the collaboration could get off the ground Michael decided to leave Flow Laboratories in order to pursue other opportunities. One opportunity Michael seized was the establishment of Centocora company that would come to play an important role in my work and life.