SPEAK BIRD, SPEAK AGAIN

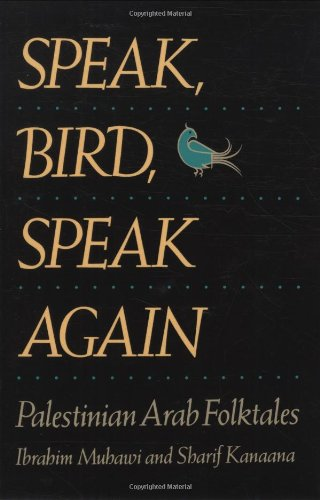

The bookcontains a collection of 45 Palestinian folk tales drawn from acollection of two hundred tales narrated by women from differentareas of historic Palestine (the Galilee, the West Bank, and Gaza).The stories collected were chosen on the basis of their popularity,their aesthetic and narrative qualities, and what they tell aboutpopular Palestinian culture dating back many centuries. The authorsspent 30 years collecting the material for the book Speak, Bird,Speak Again: A book of Palestinian folk tales is a book firstpublished in English in 1989 by Palestinian authors Ibrahim Muhawiand professor of sociology and anthropology at Bir Zeit UniversitySharif Kanaana. After the original English book of 1989, a Frenchversion, published by UNESCO, followed in 1997, and an Arabic one inLebanon in 2001.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTEON TRANSLITERATION

KEYTO REFERENCES

INTRODUCTION

THETALES

Noteson Presentation and Translation

GROUPI INDIVIDUALS

CHILDRENAND PARENTS

Afterword

SIBLINGS

Afterword

SEXUALAWAKENING AND COURTSHIP

Afterword

THEQUEST FOR THE SPOUSE

Afterword

GROUPII FAMILY

BRIDESAND BRIDEGROOMS

Afterword

HUSBANDSAND WIVES

Afterword

FAMILYLIFE

Afterword

GROUPIII SOCIETY

Afterword

GROUPIV ENVIRONMENT

Afterword

GROUPV UNIVERSE

Afterword

FOLKLORISTICANALYSIS

APPENDIXA: TRANSLITERATION

APPENDIXB: INDEX OF FOLK MOTIFS

APPENDIXC: LIST OF TALES BY TYPE

SELECTEDBIBLIOGRAPHY

FOOTNOTEINDEX

SpeakBird, Speak Again

PalestinianArab Folktales

IbrahimMuhawi and Sharif Kanaana

FOREWORD

It waswith great pleasure that I watched a joint collaborative effortbetween a man of letters and a social scientist come to fruition. Themarvelous results of this partnership lie in the pages ahead. Notonly are there forty-five splendid Palestinian Arab folktales to besavored, but we are also offered a rare combination of ethnographicand literary glosses on details that afford a unique glimpse into thesubtle nuances of Palestinian Arab culture. This unusual collectionof folktales is destined to be a classic and will surely serve as amodel for future researchers in folk narrative.

Forthe benefit of those readers unfamiliar with the history of folktalecollection and publication, let me explain why Speak, Bird, SpeakAgain: Palestinian Arab Folktales represents a significant departurefrom nearly all previous anthologies or samplers of folktales. Whenthe Grimm brothers collected fairy tales, or Marchen, from peasantinformants in the first decades of the nineteenth century, they didso in part for nationalistic and romantic reasons: they wanted tosalvage what they regarded as survivals of an ancient Teutonicheritage, to demonstrate that this culture was the equal of classical(Greek and Roman) as well as prestigious modern (French) cultures.The publication of Kinder-und Hausmarchen in 1812 and 1815 sparked ahost of similar collections of fairy tales from other countries byscholars imbued with the same combination of nationalism andromanticism. By the end of the nineteenth century, numerous folkloresocieties and periodicals had been initiated to further thecollection and analysis of all types of traditional peasant art,music, and oral literature.

Unfortunately,despite the laudable stated aims of these pioneering collectors topreserve unaltered the precious folkloristic art forms of the localpeasantry, all too often they actually rewrote or otherwisemanipulated the materials so assiduously gathered. One reason forthis intrusiveness was the longstanding elitist notion that literateculture was infinitely superior to illiterate culture. Thus the oraltales were made to conform to the higher canons of taste found inwritten literature, and oral style was replaced by literaryconvention. The Grimms, for example, began to combine differentversions of the "same" folktale, producing composite textswhich they presented as authentic - despite the fact that noraconteur had ever told them in that form.

TheGrimms and their imitators were trying to create a patrimony forpurposes of national pride (long before Germany was to become anation in the modern sense), and tampering with oral tradition suitedtheir goals. Texts that are rewritten, censored, simplified forchildren, or otherwise modified may well be enjoyed by readersconditioned to the accepted literary stylistics of so-called highculture. Such texts, however, are of negligible scientific value. Ifone wishes to understand peasant values and thought patterns, oneneeds contact with peasant folktales, not the prettified,sugar-coated derivatives reworked by dilettantes.

Sad tosay, the vast majority of nineteenth-and even twentieth-centuryfolktale collections fail to meet the minimum criteria of scientificinquiry. The tales are typically presented with no cultural contextor discussion. Of their meaning (we do not even know if their tellerswere male or female), and rarely is a concerted attempt made tocompare a particular corpus of tales with other versions of the sametale types. Let the reader think back on folktale anthologies he orshe may have read, as either a child or an adult. How many of thesestandard collections of folktales contained any scholarly apparatuslinking the content of particular tales to the cultures from whichthey came? Appallingly, these criticisms apply even to collections offolktales published by reputable folklorists. The highly regardedFolktales of the World series, published by the University of ChicagoPress, for example, includes volumes of bona fide folktales from manycountries, but the tales are accompanied by only minimal comparativeannotation. The reader may be informed that a given folktale isidentifiable as an instance of an international tale type (as definedby the Aarne-Thompson typology, available since 1910), but little orno information is given on how the tales reflect, let us say, German,Greek, or Irish culture as a whole. This criticism applies as well tomost folktale anthologies published in other countries.

Anotherreason for the inadequacy of nineteenth-century folktale collections,especially those representing countries outside Europe, is that thecollectors were typically not from the place where the tales weretold. English, French, German, and other European colonialistadministrators, missionaries, and travelers recorded stories theyfound quaint or amusing. Either informants self-censored the tales toprotect their image or else the collectors, who were not necessarilyfully fluent in the native languages, simply omitted details theydeemed obscene (by their own cultures' standards) or elements thatwere not altogether clear to them. Thus most nineteenth-centurycollections of tales from India or the Middle East contain only theblandest tales, sometimes in severely abridged or abstract form, withno hint of even the slightest bawdy or risqu motifs. Althoughfolklorists today are not ungrateful for these early versions offolktales, they cannot condone the lack of honesty in the reportingof them. What remains badly needed are collections of folktales madeby fieldworkers whose roots are in the region and who speak thenative language of the taletellers.

In thepresent volume we have two scholars with the requisite expertise.Ibrahim Muhawi was born in 1937 in Ramallah, Palestine (nine milesnorth of Jerusalem). After completing high school at the FriendsBoys' School in Ramallah, he went to the United States where, in1959, he earned a B.S. in electrical engineering at Heald EngineeringCollege in San Francisco. Then came a dramatic shift of intellectualgears, with a B.A. (magna cum laude) in English from California StateUniversity at Hayward (1964), followed quickly by an M.A. (1966) anda Ph.D. (1969), both also in English, from the University ofCalifornia, Davis. After teaching English at Brock University in St.Catharines, Ontario, Canada (1969-1975), and at the University ofJordan in Amman (1975-1977), Muhawi joined the English department atBirzeit University in the West Bank, where he served as departmentchairman from 1978 to 1980. It was there that he met the coauthor ofthis book.