Contents

Guide

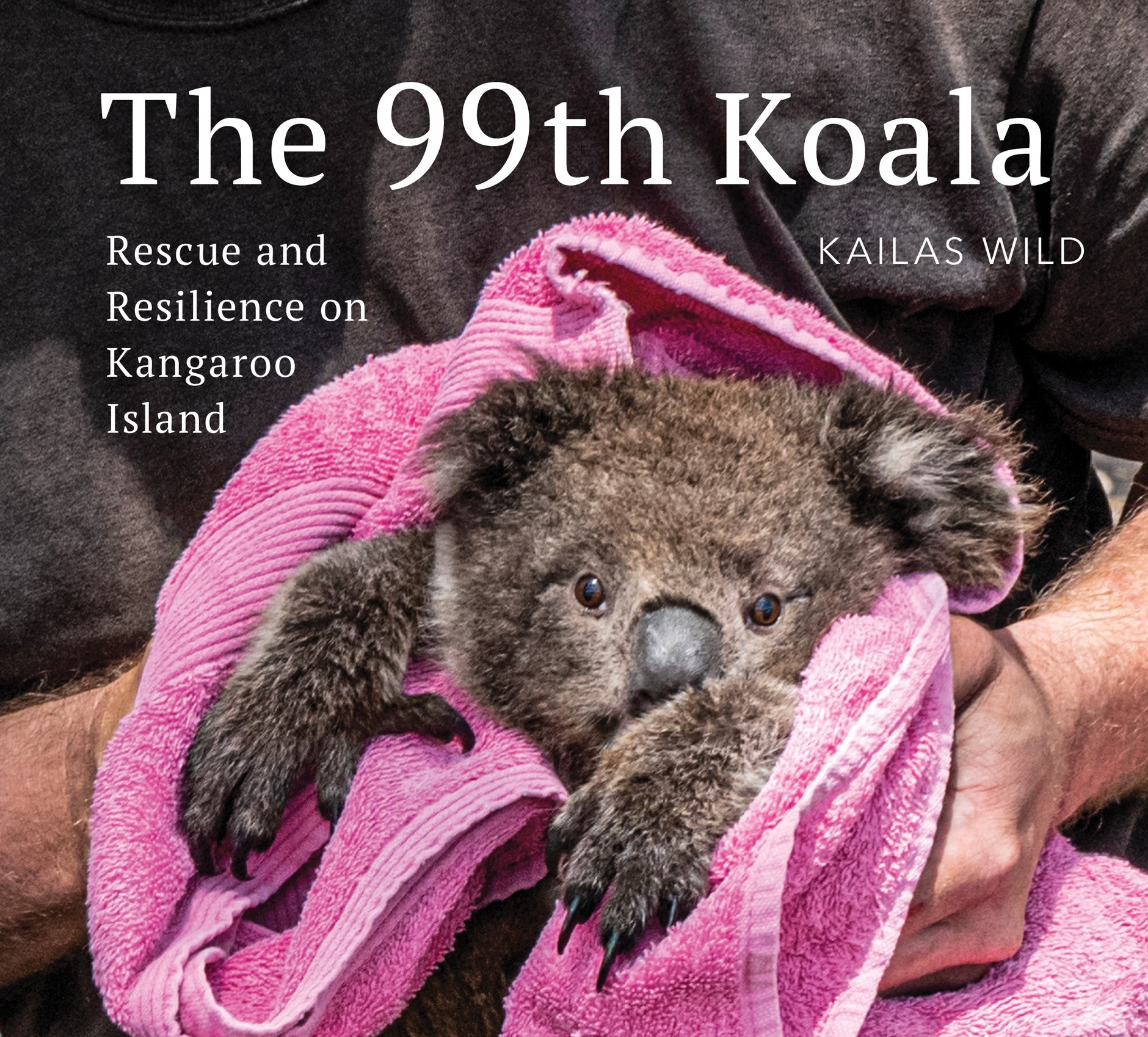

Australias Black Summer bushfires were absolutely devastating. A combination of unprecedented heat and dryness meant that fires took hold with an intensity not seen before, and without sufficient rain, they felt unstoppable. Between June 2019 and February 2020 over 12 million hectares were destroyed. Every state and territory was affected almost every person in the country was touched in some way.

Maybe you were one of those Australians living in the bush under threat of fire. Maybe your town or city was blanketed by the thick deadly smoke, which even drifted across the Pacific Ocean to New Zealand, turning skies there hazy yellow. If you were lucky enough to have escaped both, then chances are you were anxious about someone who hadnt been. As a country, our hearts went out to those whose safety was threatened, who lost their homes, and most of all those who lost loved ones. At least 34 people died.

We all shared the profound sense of grief at the loss of over a billion of our unique wild animals, along with their habitats. The number was, and still is, beyond comprehension.

For months we all felt helpless, myself included.

This is the story of what I did in response to that feeling to try and help wildlife, and also myself. The seven weeks I spent on fire-ravaged Kangaroo Island helping rescue koalas were some of the most gruelling but rewarding of my life an experience that has changed me in ways Im still learning about.

Fire

My first encounter with the destructive nature of fire was at the age of ten: I arrived home from school to find fire engines on our 12-acre bushland property. A small fuel reduction burn had smouldered underground for days before bursting into life and threatening the house when everyone was out except my 80-year-old nan. Ill never forget my nan telling me not to worry my mum, who was at work at the time, and later my mum being as shocked that she hadnt been told as she was by the fire itself.

A couple of years later, a candle Id left alight in my bedroom led to the room burning to the ground. Luckily, it was separate from the main house but I can still remember the sound of glass exploding and how scared and helpless I felt as I watched on, completely incapable of doing anything to stop it. The experience drew a line under my childhood.

The Black Summers megafires also moved me onto a different stage of my adult life.

My direct contact with the fires began on 13 September 2019. An ecologist friend of mine, Mark, was helping fight the Bees Nest fire that threatened the rainforest adjoining the World Heritage Mount Hyland Nature Reserve, on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales. I went up to help. For a week, alongside the property owner Rosie and other community volunteers, we used dry, manual techniques to hold containment lines, clear around rough-barked trees to stop fire travelling up their trunks into their canopies, put out fires that were edging their way through rainforest and took shifts throughout the night to ensure the fire hadnt managed to jump. Im an arborist by trade, so I helped reduce the major fuel loads in the fire path and clear burnt trunks that had fallen across access roads and evacuation routes. We managed to save some small patches of forest, and Rosies house survived, but 50,000 acres were lost in that fire alone.

Cool temperate rainforest is typically cold and damp as the name suggests, and seeing it burn barely out of winter was a major, terrifying warning signal for what was to come as summer approached.

My second encounter with the fires was closer to home, north-west of the Blue Mountains at Running Stream. On 18 December, my then-partner Ellas family were preparing for the Palmers Oaky fire which was approaching their property. With winds expected to pick up in their direction, I drove up from Sydney to help them defend their home.