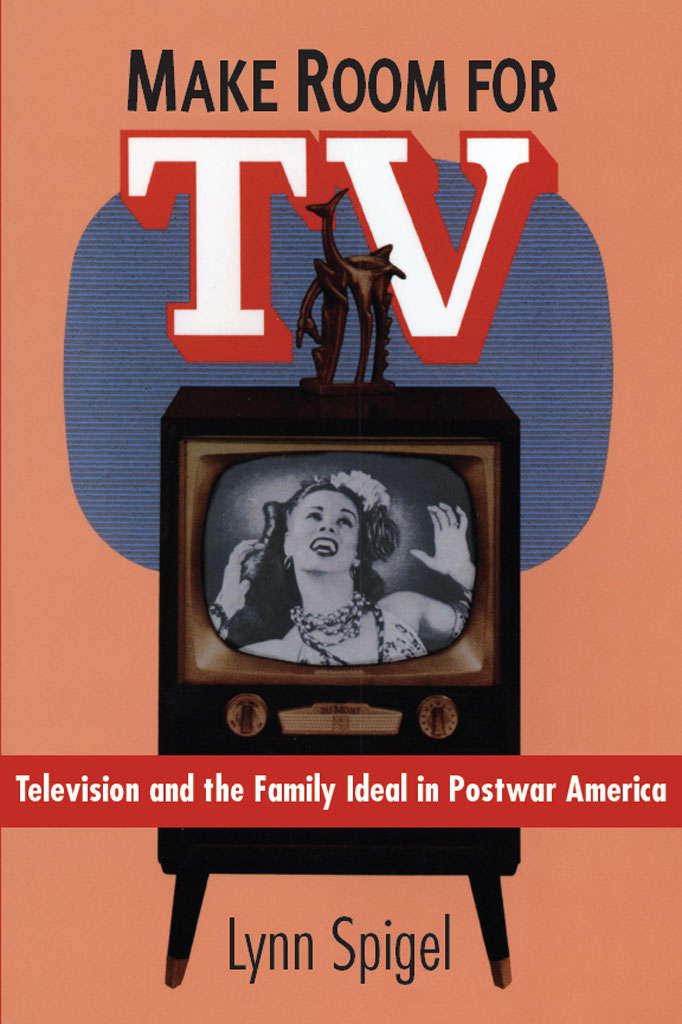

Lynn Spigel - Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America

Here you can read online Lynn Spigel - Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: University of Chicago Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Chicago Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lynn Spigel: author's other books

Who wrote Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1992 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1992

Printed in the United States of America

14 13 12 11 8 9 10 11

ISBN 978-0-226-76963-9 (e-book)

ISBN (cloth): 0-226-76966-6

ISBN (paper): 0-226-76967-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Spigel, Lynn.

Make room for TV : television and the family ideal in postwar America / Lynn Spigel.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Television and familyUnited States. I. Title.

HQ520.S75 1992

306.87dc20

91-32770

CIP

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

MAKE ROOM FOR TV

Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America

Lynn Spigel

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

To

Bill Forman

and to my parents,

Roslyn and Herman Spigel

This book is a product of a dialogue with friends, family, and colleagues who gave me their support and encouragement. The people I want to thank will recognize their particular contributions.

I first wish to express my deepest gratitude to Bill Forman for his editorial suggestions. He saw this project through its six-year span and lived through the numerous forms it has taken. His willingness to reread chapters and provide new thoughts is a true act of kindness.

I also want to thank the numerous people who helped foster and spur ideas for this project. Janet Bergstrom was irreplaceable, both as a friend and as a teacher. Her intuitive intelligence and nonconformist scholarship have greatly influenced this work and my general understanding of feminist collaboration. Nick Browne devoted many hours to the formation of this study when it was first conceived in graduate school. His efforts have had an enormous impact on this book and on my thinking in general. George Lipsitz had a special role in the books formation, both through his own imaginative writings on American popular culture and through his direct support of my research. Robert Allen read numerous drafts and inspired me with his vision of American cultural history. Lary May encouraged the transformation of my research into a book and influenced its contents with his own writings on American cultural history. Douglas Mitchell, my editor at the University of Chicago Press, had faith in this project from the start and always offered guidance and encouragement. Kathryn Montgomery, Paul Rosenthal, William Roy, and Kathryn Kish Sklar all provided insights in the early stages of this study. I also extend my warmest gratitude to other family, friends, and colleagues, including Marcia Untracht, Margie Solovay, Chris Berry, Denise Mann, Mary Beth Haralovich, Constance Penley, Elisabeth Lyon, Henry Jenkins, William Lafferty, Thomas Streeter, Michael Curtin, Jackie Byars, David Eason, Cory Creekmur, Beatriz Colomina, Patricia Mellencamp, Lauren Rabinovitz, Lisa Freeman, Charlotte Brunsdon, David Morley, Richard deCordova, Matthew Geller, William Boddy, and Mary Carbine.

Certainly, this book would not have been possible without the collegial support, insights, and goodwill of my colleagues at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. I especially want to thank Julie DAcci, John Fiske, David Bordwell, Kristin Thompson, Tino Balio, J. J. Murphy, and Jeffrey Sconce for their willingness to discuss ideas, make suggestions, and provide a context of generous collaboration. I am also indebted to Maxine Fleckner and Don Crafton at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Television Research; Eleanor Tannin, Robert Rosen, Steven Ricci, and Dan Einstein at the UCLA Archives; William Bird at the Smithsonian Institution; and my research assistants Aimee Lefkow, Reg Shrader, Shelley Happy, and Paul Seale.

Finally, I want to express my gratitude to my mother Roslyn and my father Herman Spigel, with whom I did my first fieldwork. A TV repairman for Macys department store, my father took me out to his customers homes where I sat curiously watching him tinker with the tubes and wires of TV consoles located somewhere in the outer limits of postwar suburbia. Memories like that always make for odd connections between history and life.

In 1927, the American modernist architect R. Buckminster Fuller built his famous Dymaxion House, a glass octagonal structure supported by a steel frame, one of the first in a history of homes of tomorrow to include a television set. When Fullers house was first displayed to the public in 1929 at Marshall Fields department store in Chicago, it was scarcely more than a science fiction oddity to the curious onlookers who were told that the home would one day be produced on assembly lines across the nation. The television set, placed in what Fuller called the get-on-with-life-room along with a radio, phonograph, and numerous domestic office machines, seemed to be, like the house itself, an alien contraption to the customers at the Chicago store. Twenty years after the Marshall Fields exhibit, Fullers dream for mass-produced housing would become a reality, albeit in a completely transmuted form. In 1949, on the unlikely spot of a potato field in Hempstead, Long Island, more than 1,400 people lined up on a cold March morning anxiously waiting to purchase their very own home of tomorrow, a prefabricated Cape Cod/ranch-style cottage filled with modern labor-saving appliances and located in the most famous of the mass-produced suburbs, Levittown. Although these eager consumers were the first on their block to become Levitt families, it wasnt until the following year that the developer introduced his newest built-in feature, an Admiral television permanently embedded in the living room wall. In less than a quarter of a century, the television set had become a staple fixture in the American family home.

This book is a cultural history of American television, concentrating upon its installation into domestic space in the years following World War II. During this period, the primary site of exhibition for spectator amusements was transferred from the public space of the movie theater to the private space of the home. Americans purchased television sets at record ratesin fact more quickly than they had purchased any other home entertainment machine. Between 1948 and 1955, television was installed in nearly two-thirds of the nations homes, and the basic mechanisms of the network oligopoly were set in motion. By 1960, almost 90 percent of American households had at least one receiver, with the average person watching approximately five hours of television each day.

How, over the course of a single decade, did television become part of peoples daily routines? How did people experience the arrival of television in their homes, and what were their expectations for the new mass medium? Routine events such as television viewing are part of the often invisible history of everyday life, a history that was not recorded by the people who lived it at the time. In order to understand such historical processes, it is necessary to examine unconventional sources, sources that tell us somethinghowever partialabout the ephemeral qualities of daily experiences. This study originated some five years ago when I began to look in popular womens magazines in order to see how television had been advertised to its first consumers. I did find advertisements, but I also found something elsea wealth of representations of and debates about televisions relationship to family life. These popular sources expressed a set of cultural anxieties about the new medium as they engaged the public in a dialogue concerning televisions place in the home. This book investigates that dialogue by examining how popular media introduced television to the public between 1948 and 1955, the years in which it became a dominant mass medium. During this period, magazines, advertisements, newspapers, radio, film, and television itself spoke in seemingly endless ways about televisions status as domestic entertainment. By looking at these media and the representations they distributed, we can see how the idea of television and its place in the home was circulated to the public. Popular media ascribed meanings to television and advised the public on ways to use it. While the media discourses do not directly reflect how people responded to television, they do reveal an intertextual contexta group of interconnected textsthrough which people might have made sense of television and its place in everyday life.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America»

Look at similar books to Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.