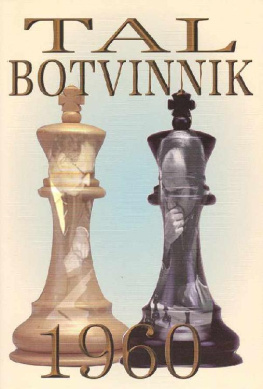

Tal-Botvinnik

1960

Match for the

World Chess Championship

Mikhail Tal

2010

Russell Enterprises, Inc.

Milford, CT USA

Tal-Botvinnik 1960

Match for the World Chess Championsip

by Mikhail Tal

Copyright

1970, 1972, 1976, 1996, 2000, 2003 2010

Hanon W. Russell

All rights reserved under Pan American and International Copyright Conventions.

No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

ISBN: 978-1-888690-08-8

Published by:

Russell Enterprises, Inc.

PO Box 3131

Milford, CT 06460 USA

http://www.russell-enterprises.com

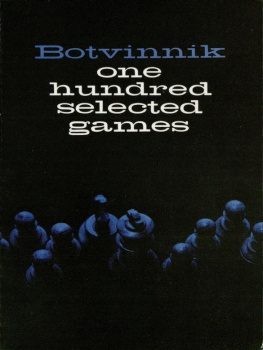

Front Cover: On the front, facing each other as kings of chess, Mikhail Botvinnik (left) and Mikhail Tal. Tal is shown at about the age that his great adversary was during their match. Back Cover: Tal is shown two years after his victory, a young world champion with a wide grin for the world.

Cover design by Out Excel! Corp., Al Lawrence, President; Jami Anson, Art Director. The publisher wishes to express its thanks to Glenn Petersen, editor of Chess Life and the United States Chess Federation for permission to reprint the photographs contained in this book.

Table of Contents

From the Author

In the spring of 1960, two Soviet chessplayers again met each other in the match for the championship of the world. This time, I played the role of challenger.

I will not hide the fact that it was very flattering that the world championship match between Botvinnik and me aroused great interest among chessplayers. All the match games were analyzed in detail in the pages of the press. Grandmaster Ragozin headed the remarkable analysts who, soon after the finish of the duel, published books about the match. To add something to their variations is a problem which is by no means easy.

But this author has not tried to do that. His goal was not to discover some move in the struggle through the eyes of a detached spectator, but to try to give the personal feelings, thoughts, agitation, and disappointments of a direct participant in the combat. Let the reader not complain that, in this book, he will not see Tal, figuratively speaking, in a starched white shirt and tie, but in his working clothes; I will relate the story of the match, basically, from the beginning of this intense duel.

Of course, such a book might be, to a certain extent, one-sided. I therefore placed before myself one goal - to reveal to the reader, in detail, the dialectical developmental process of a chess game, beginning with the opening. A book this size does not permit me to give an opening manual, and in fact, such would be beyond the scope of this endeavor.

Each game is prefaced with a small introduction, in which I discuss the attitude before the game, or go in for a small lyrical digression, sharing my thoughts that I had at the time of the match.

Mikhail Tal

Riga

September, 1960

Before the Match

The cherished dream of every chessplayer is to play a match with the world champion. But here is the paradox: the closer you come to the realization of this goal, the less you think about it. At the very beginning of my creative path I mentally depicted my meeting with Botvinnik more than once. Botvinnik the hero of our generation, on whose games and labors more than one Pleiad of Soviet chessplayers has been nurtured. Later, this goal became less of a dream as I became a member of the large group of participants who were to play a series of tournaments leading to the right to play a match with the world champion. However, current affairs somehow pushed these sweet dreams into the background. Curiously enough, at the time of the Candidates Tournament, I did not find myself once dreaming those dreams which until recently had seemed so forbidden. But the tournament ended, I had succeeded in taking first place and had earned the right to play the match.

It then would seem that there was not a minute to lose before preparations for the match should begin. Far from it. My nervous reaction after that marathon tournament had been so great that I was in no condition to think about the match, or for that matter, any serious chess work. And there was not much time before the beginning of the match less than six months. Rather than venturing it myself, Alexander Koblents and I began the business of discussing the problems of preparation for the most important event in my life.

Until that time, I had considered myself, and not without reason, among the ranks of tournament chessplayers I had only had one occasion to play an actual match (that was in 1954, when I, to tell the truth, really did not imagine that it was necessary to prepare for such a contest). Therefore I was completely unfamiliar with the specific character of this type of competition.

Nevertheless, there exists a huge difference between tournament and match play. First of all, to express it coarsely, there is the bookkeeping. While in a tournament a participant is not bound by his point showing at least in the first part of the tournament and can venture the luxury of staying up late at the start, each match game is equally important. You see, in a match there are no other competitors, no outsiders and a chessplayer cannot plan in advance from whom he will win without fail, with whom a draw will be sufficient and (as often happens!) to whom it will not be shameful to lose. The cost of each point in a match in comparison with a tournament grows twofold: if one chessplayer wins, then his rival automatically loses, and therefore match games always evoke a greater feeling of responsibility.

Matches have their own psychological character. If in the Candidates Tournament, I became weary meeting one and the same opponent four times (and this was after an interval of seven rounds!), then what is to be said about a match, in which I would meet the same chessplayer day in and day out? This is even more taxing.

Finally, the problem of preparing for a match is also significantly more difficult. I have not yet mentioned that my opponent was an unsurpassed master of home preparation. If I often employed risky variations, it may have worked out in a tournament; if I put my hopes on some risky opening adventure in a match, my bluff was certain to be called.

In a word, I had comparatively little time in which to study the ABCs of match play, while my opponent, in the last ten years, had defended his Championship Dissertation only in this milieu. And, actually, when we began to go over games played by Botvinnik since he had won the title of world champion (1948), it did not take much to convince us that the overwhelming majority of them were played in title matches, in which he had three times defended his title, and once recovered it.

I was often chided for the fact that only one month after the conclusion of the Candidates Tournament, I entered the First International Tournament at Riga (and it was extremely unimportant). Here I must frankly admit that this appearance was also one of the ingredients of my preparation for the match. Chess fans, probably, focused their attention on the fact that in the majority of my games in this tournament, I turned out to be on the defensive, sometimes right from the opening. Inasmuch as defense has always been my Achilles Heel, I did not treat it lightly. In all fairness, it must be noted that the pace was set by the two winners of the tournament, Boris Spassky and Vladas Mikenas; their results at the end were so impressive, that I, at no time in this competition, saw any possibility of being their equal.