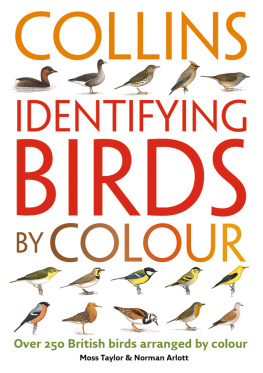

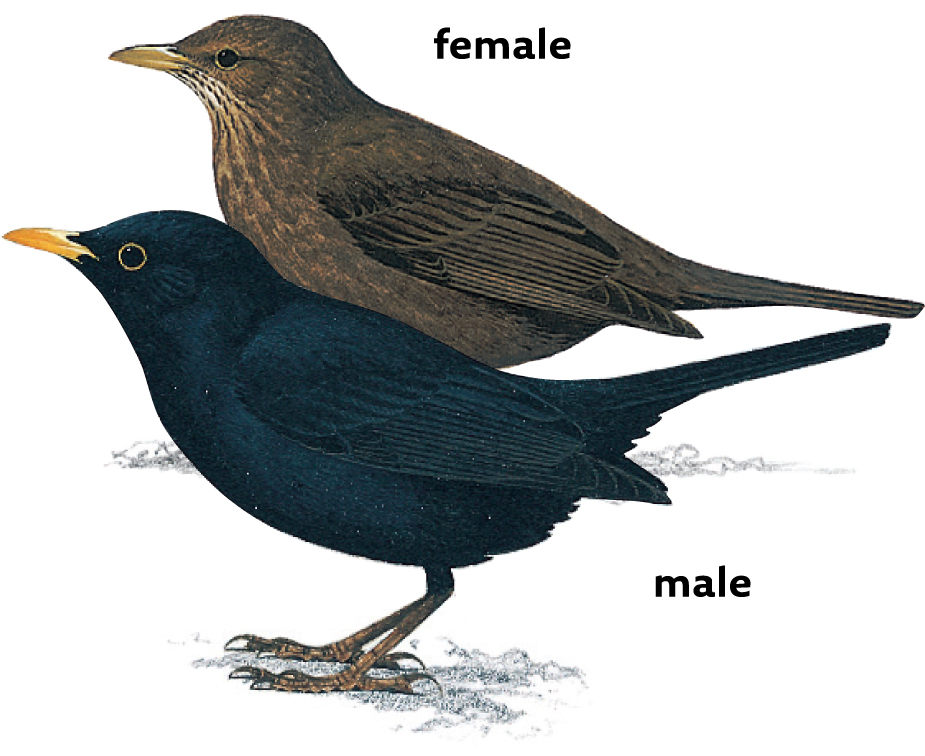

The Blackbird appears twice the male in the black section, the female in the brown.

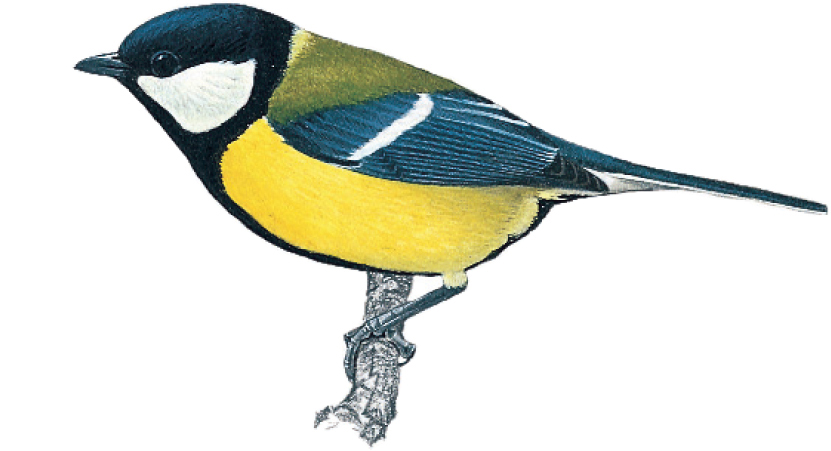

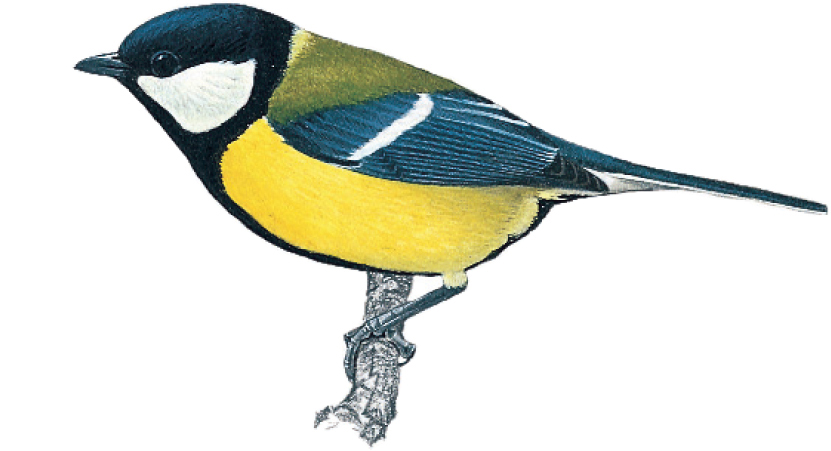

With its black cap, yellow breast and blue-grey wings, the Great Tit appears several times.

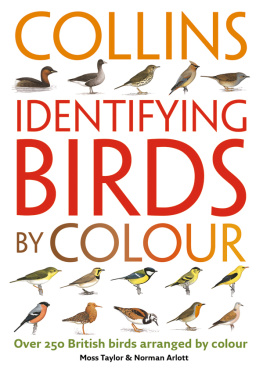

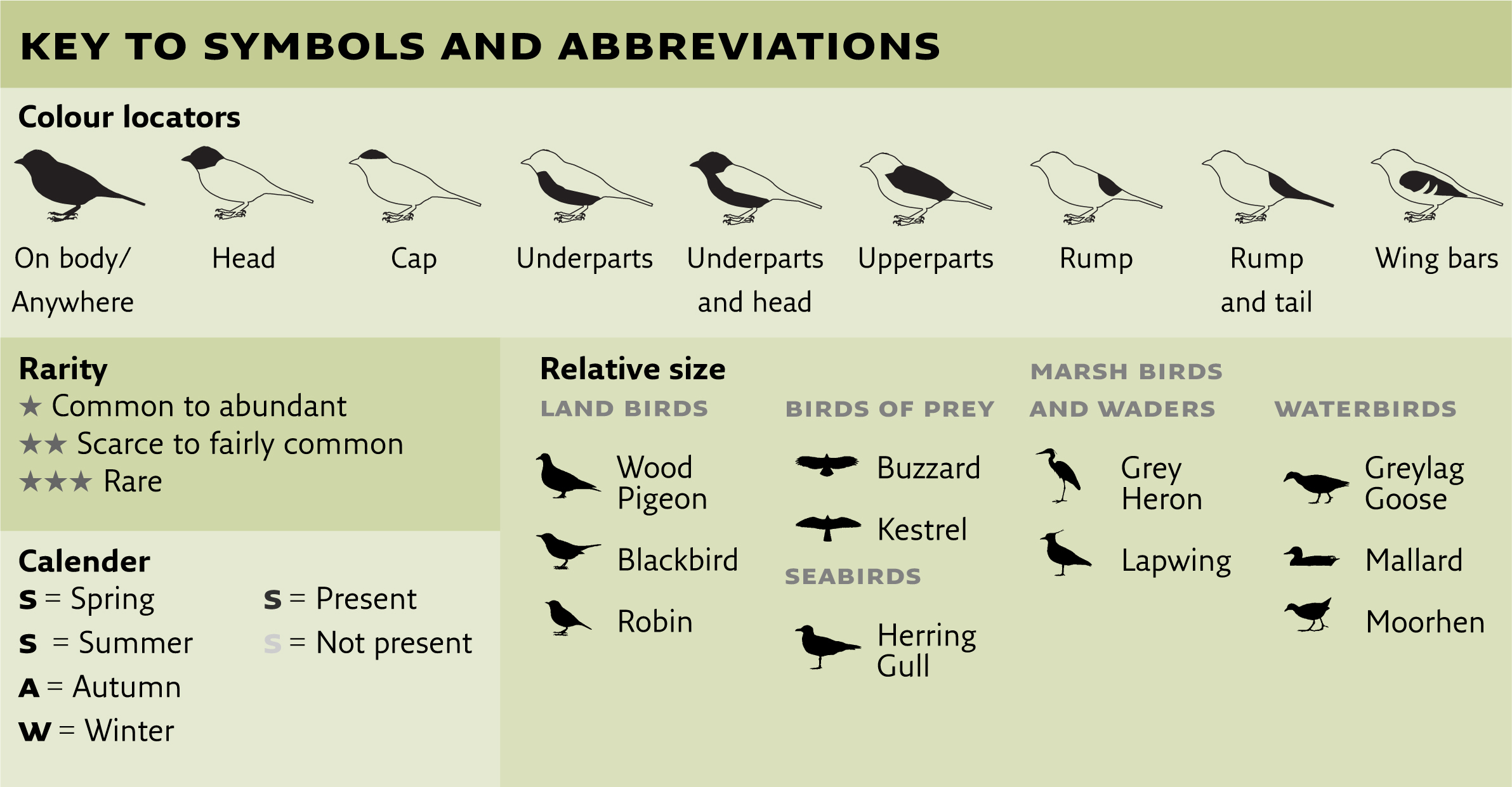

Within each colour section the birds are further arranged into three main groups which are themselve subdivided as follows: land birds (including birds of prey, owls and game birds), marsh birds and waders, and waterbirds (including seabirds). Although the order of colours is somewhat arbitrary, they do roughly follow the colours of the rainbow, commencing with the reds (red, pink, chestnut and orange), through brown, yellow, green, blue and grey, to white and finally black. On the whole, birds are not shown in flight, because colour is rarely used for identifying birds in the air. But where a colour feature is best seen in flight such as a chestnut rump or white wing bars birds are also shown flying.

Of course, features other than colour are used in bird identification, some of which have been alluded to above, such as size and the habitat in which a bird is usually found. Other clues might be shape, type of bill, leg length, voice and behaviour, some of which are expanded on below. Any such additional characteristics are also included in the species accounts accompanying the illustrations.

As well as the illustrations and species texts, this book contains an introduction to the daily lives of birds, some tips for novice birdwatchers, a glossary of some of the terms used in the text and suggestions for further reading. It is very much meant as a basic introduction to bird identification for readers of all ages, using colour as the initial means of recognising the commonest species that occur in Britain and Ireland.

Which birds are included?

About 190 species breed annually in Britain and Ireland and many others occur in winter or on migration. One of the problems for beginners is separating out those species they are most likely to record during their early birdwatching days from those they are least likely to see. Not doing so can easily lead to errors in identification. Its always worth remembering that common birds occur commonly and by definition rarities are just that rare!

This book, then, largely confines itself to those species that are regularly recorded in Britain and Ireland in a genuinely wild state, including all those that breed annually. Only a few rarer species are included. The selection is, to a certain extent, an arbitrary one and readers may well feel that other species should have been included, while some should have been omitted. In addition, some birds, such as the Rose-ringed Parakeet, have been featured because they are seen regularly as escapes or feral birds and rarely pass unnoticed! In general, subspecies (races) are not included unless they occur relatively frequently and are readily identifiable in the field.

For most species, the illustrations are confined to adults, with both sexes illustrated only where there are noticeable plumage differences between the two. With the exception of swans, immature birds are not included. Where there is a marked difference between the breeding and non-breeding plumages of a bird, such as the Golden Plover, both may be illustrated in the relevant colour sections.

Relative rarity value

While it can be exciting to see any species, particularly when first taking up birdwatching, it is always more satisfying to find and identify the less common birds. With this in mind, and in an attempt to classify their relative scarcity value, species are rated in increasing rarity as one-, two- or threestar birds. It must be remembered, however, that what is common in the south of England may be rare in Scotland or Ireland, and vice versa. Thus the Jay is given one star and yet is virtually unknown in the far north of Scotland, while the White-tailed Eagle is given three stars but may well be seen almost daily by residents of some of the Scottish isles. Some of the least common birds are ones that occur in Britain and Ireland only as migrants, usually in the spring or autumn.

The naming of birds

Unfortunately, English bird names have been going through a period of change in recent years and it is almost impossible to arrive at a standard list that is acceptable to all organisations and journals. The names used in this book are those that are most often used by birdwatchers in Britain and Ireland. To overcome this problem, and to be absolutely clear which species is being described, the scientific name is also given after the more familiar English one. The binomial system that uses two Latin words is universally recognised and is unique for every species, although even these names have been updated recently in the light of new DNA research.

Relative sizes of birds

Most books on bird identification give absolute measurements of the birds length and wingspan in centimetres. These figures actually mean very little to most people. The system adopted in this book is to compare the size of each bird with the silhouettes of up to three common species that occupy the same habitat and are likely to be recognised by most readers. Thus land birds are compared with a Wood Pigeon, Blackbird or Robin, marsh birds and waders with a Heron or Lapwing, waterbirds with a Greylag Goose, Mallard or Moorhen, and seabirds with a Herring Gull. The only exceptions are the birds of prey, which are compared with a Buzzard or Kestrel. Size comparisons are only approximations and take into account the general appearance of the bird in the field. Where the size is noticeably larger (>) or smaller (<) than the comparative species, this is denoted by the appropriate symbol. Note that colour illustrations on a page are not shown in relative size to each other.