Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

LINER NOTES

FOR THE

REVOLUTION

THE INTELLECTUAL LIFE OF BLACK FEMINIST SOUND

DAPHNE A. BROOKS

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTSLONDON, ENGLAND2021

Copyright 2021 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Cover design: Tim Jones

Cover image: Photograph courtesy of Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

978-0-674-05281-9 (hardcover)

978-0-674-25881-5 (EPUB)

978-0-674-25880-8 (PDF)

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PRINTED EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Names: Brooks, Daphne, author.

Title: Liner notes for the revolution : the intellectual life of black feminist sound / Daphne A. Brooks.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020030775

Subjects: LCSH: African American women musicians. | African American womenMusicHistory and criticism. | African American womenIntellectual life. | Musical criticismUnited StatesHistory. | African American feminists.

Classification: LCC ML3556 .B74 2021 | DDC 780.82/0973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020030775

In Memory of Lodell Brooks Matthews

In Honor of Juanita Kathryn Watson Brooks

and

for Matthew Frye Jacobson

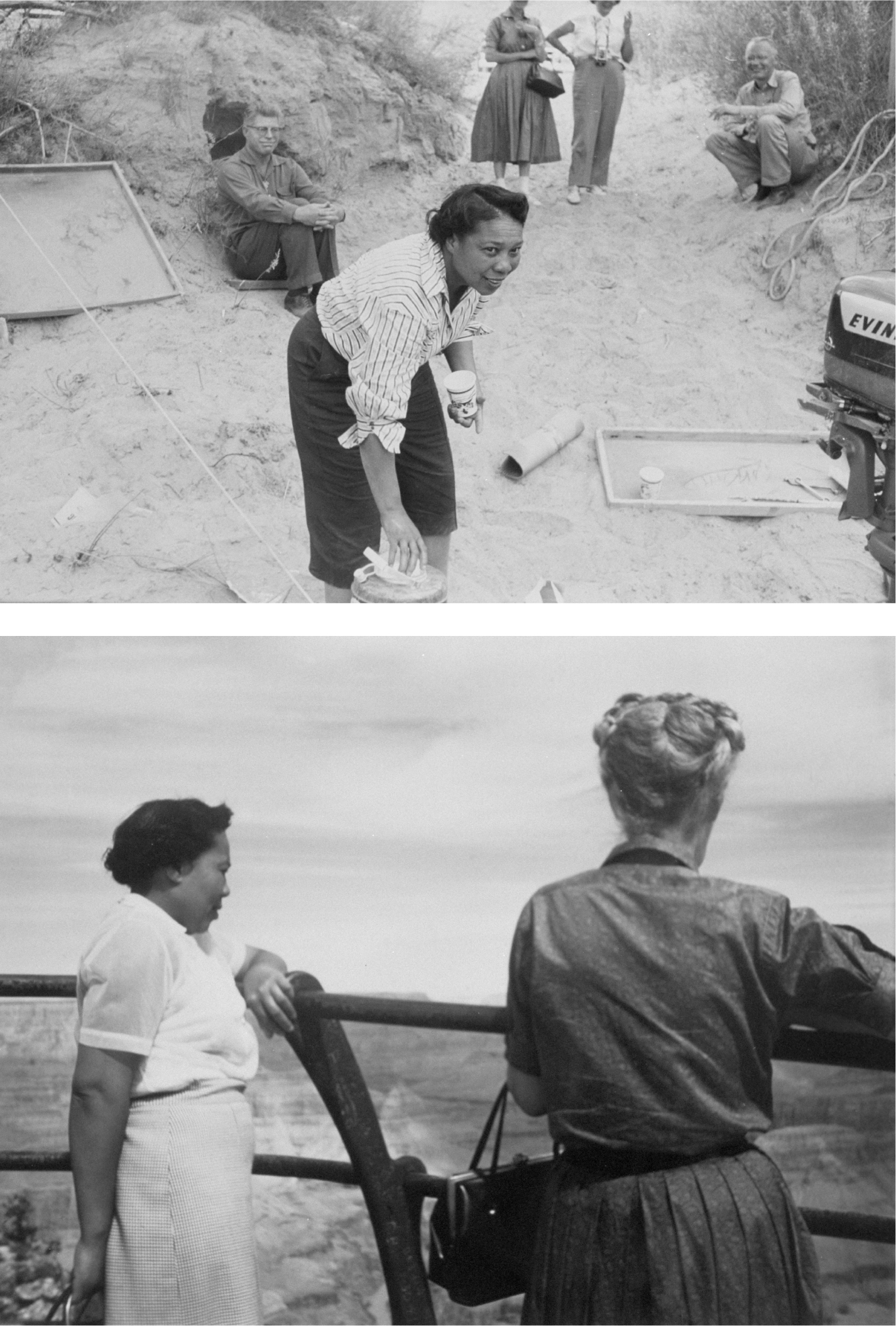

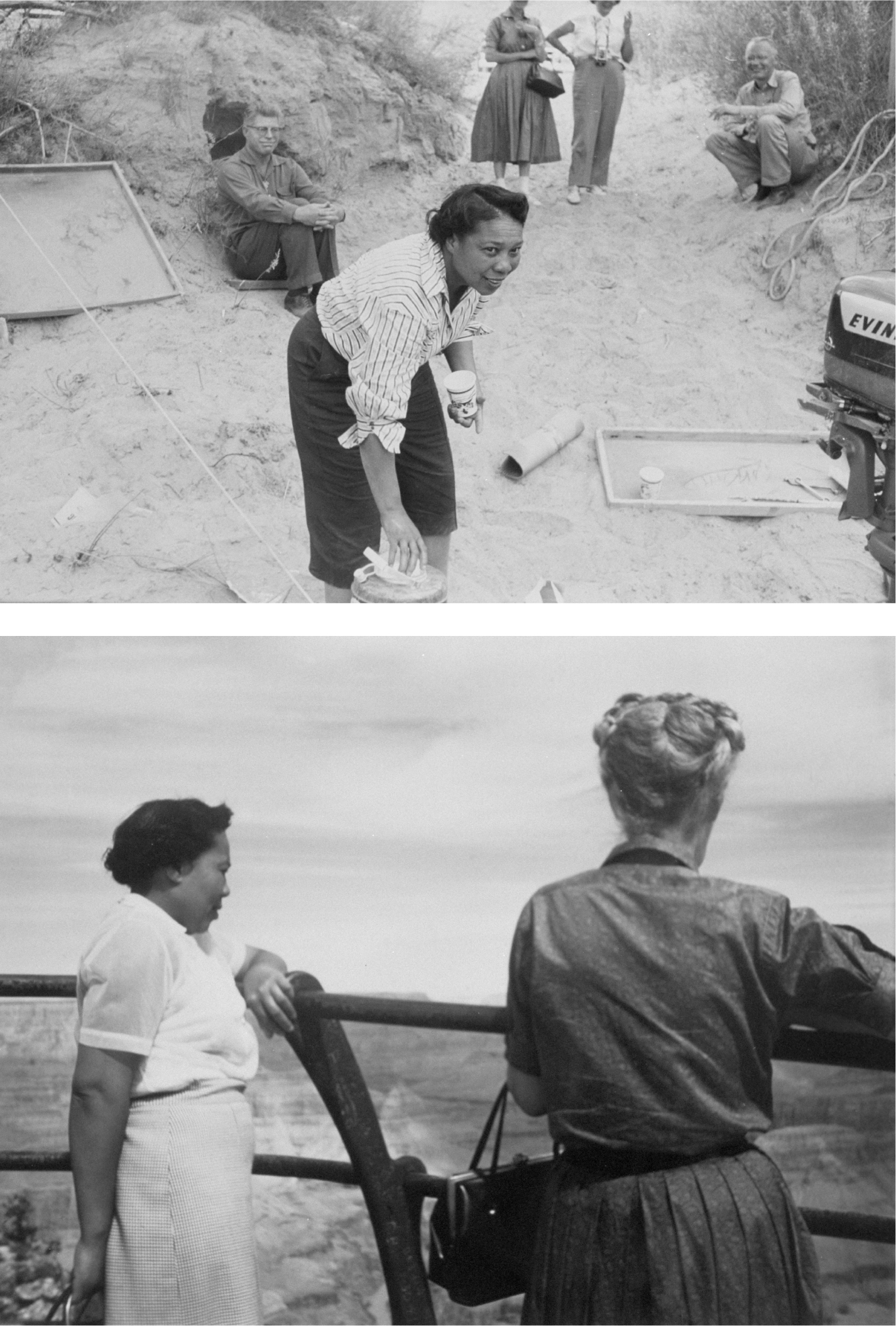

The authors aunt, Lodell Matthews, at the Colorado River circa 1956

Lodell Matthews and Margaret Marston take in the Points, circa 1956

CONTENTS

Throughout this book, I use the terms African American and Black interchangeably. Readers will note a variety of texts which I cite that do so as well. I also make use of a number of other works which use black for this same point of reference. All of these variations refer to people of African descent, and my decision to turn back to capitalizing Black is done so in the spirit of emphasizing a core principle framing this books aims: to reveal and explore the shared sociohistorical and cultural conditions of various peoples of African descent resulting from systemic subjugation across space and time. P. Gabrielle Foremans invocation of nineteenth-century journalist T. Thomas Fortunes resoundingly emphatic reasoning for this practice, quoted in her own Note on Language (in Activist Sentiments: Reading Black Women in the Nineteenth Century [Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009], xv), is instructive, and so I reference it here as well and with great thanks to Foreman for setting yet another example for me. Says Fortune in his 1906 speech entitled Who Are We, I AM A PROPER NOUN, NOT A COMMON NOUN.

Two hundred and forty-six years of outward submission during slavery time got folks to thinking of us as creatures of task alone. When in fact the conflict between what we wanted to do and what we were forced to do intensified our inner life instead of destroying it. We developed turtle shell. So when folks come feeling around they find something smooth and round and simple on the outside. Like the six blind men who felt all over the elephant. But if more had been known about us, this mistaken simplicity never would have got abroad.

ZORA NEALE HURSTON, You Dont Know Us Negroes

Quiet as its kept, Black women of sound have a secret. Theirs is a history unfolding on other frequencies while the world adores them and yet mishears them, celebrates them and yet ignores them, heralds them and simultaneously devalues them. Theirs is a history that is, nonetheless, populated with revolutionaries: turn-of-the-century vaudevillian Muriel Ringgold rocking her entirety in full costume as the sea; blues trailblazer Mamie Smith breaking the era of modern records wide open all crazy in Stagolee-style love; opera ingnue Anne Brown rewriting Bess to Gershwins Porgy; High Priestess Nina orchestrating a Brecht and Weill tempest aimed at overturning Jim Crow; and slinky Afrocosmopolitan Eartha staging her own geopolitical cabaret. Its a history wide enough to encompass rebel-with-her-own-cause rock and roller Etta James in a fast car out on the open road and folk historian Odetta going deep into scholar, thinker, rule-breaker Zoras precious vault so that the real work (songs) can begin. Its teen Aretha in shimmering sequins attacking Al Jolsons Swanee and those glam ambassadors, the Supremes, pointing us toward Somewhere one day after a King had been slain. Its the body and soul of a grown-ass musician building bridges over troubled water for her listeners; the electric kinetics of Anna Mae Bullock breaking free from domestic tyranny; funk philosopher Betty Davis inventing her own erotic lexicon; and intergalactic trio Labelle delivering Afrofuturist theory all up in the club. Theirs is a history of the utopic and the transformative, the strange and the strategically unruly: Diana reaching out and touching the hands of the multitudes in the Central Park rain; Afropunk Godmother Grace driving Atlantic World nightlife right to the edge while Poly Styrene and Skin work on burning the whole house down. Its Whitneys melisma lighting up postCivil Rights America, and its Ms. Hill with her renegade contralto scoring a thousand turn-of-the-century sorrow songs for the hip hop generation. Its a hardworking, H-town, new millennium storm system performing radical Black pop feminism to fight catastrophe, and its her avant-garde genius baby sis staging a Blackest-of-Black uprising right in the center of the lily-white Guggenheim. Theirs is a history of game-changing art that stands as an affirmation of our past as well as the unrecorded future of sound, that which is booming in the not yet, the place where all those sisters of the yam are running us straight into the dawn.

Shake That Thing: The Secret & the Subterranean Dimensions of Black Womens Sounds

Liner Notes for the Revolution tells the story of how Black women musicians have made the modern world. It is the first extensive archival interrogation of what ethnomusicologist Christopher Small has famously referred to as the musicking extending in all directions in our world made by women who have been overlooked or underappreciated, misread and sometimes lazily mythologized, underestimated and sometimes entirely disregarded, andabove all elseperpetually undertheorized by generations of critics for much of the last one hundred years. These critics and tastemakers, collectors, and far too many scholars have engaged in a long game, one that involves oversimplifying, simplistically romanticizing, and, at key moments, rapturously cry-me-a-river sentimentalizing the complexities of Black women musicians work. It is the problem of their hold on the narratives about Black womens sonic artistry that constitutes a significant portion of this book.

But make no mistake. They are not the stars of this show. Rather, it is the remarkable sisters who both have made and have been thinking and writing about Black womens music for over a century now. They are the ones who stand front and center in this study, and they are the ones who have so fundamentally reshaped structures of feeling and expressive cultural forms in the popular domain since the dawn of the twentieth century that one would be hard-pressed to imagine an American culture without their influence. But do we even know some of these sisters names? These women, this book argues, are culture