ALSO BY LIDIA MATTICCHIO BASTIANICH

Lidias Celebrate Like an Italian

Lidias Mastering the Art of Italian Cuisine

Nonna Tell Me a Story: Lidias Egg-citing Farm Adventure

Lidias Commonsense Italian Cooking

Lidias Family Kitchen: Nonnas Birthday Surprise

Lidias Favorite Recipes

Lidias Italy in America

Nonna Tell Me a Story: Lidias Christmas Kitchen

Lidia Cooks from the Heart of Italy

Lidias Italy

Lidias Family Table

Lidias Italian-American Kitchen

Lidias Italian Table

La Cucina di Lidia

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A . KNOPF

Copyright 2018 by Tutti a Tavola, LLC

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bastianich, Lidia, author.

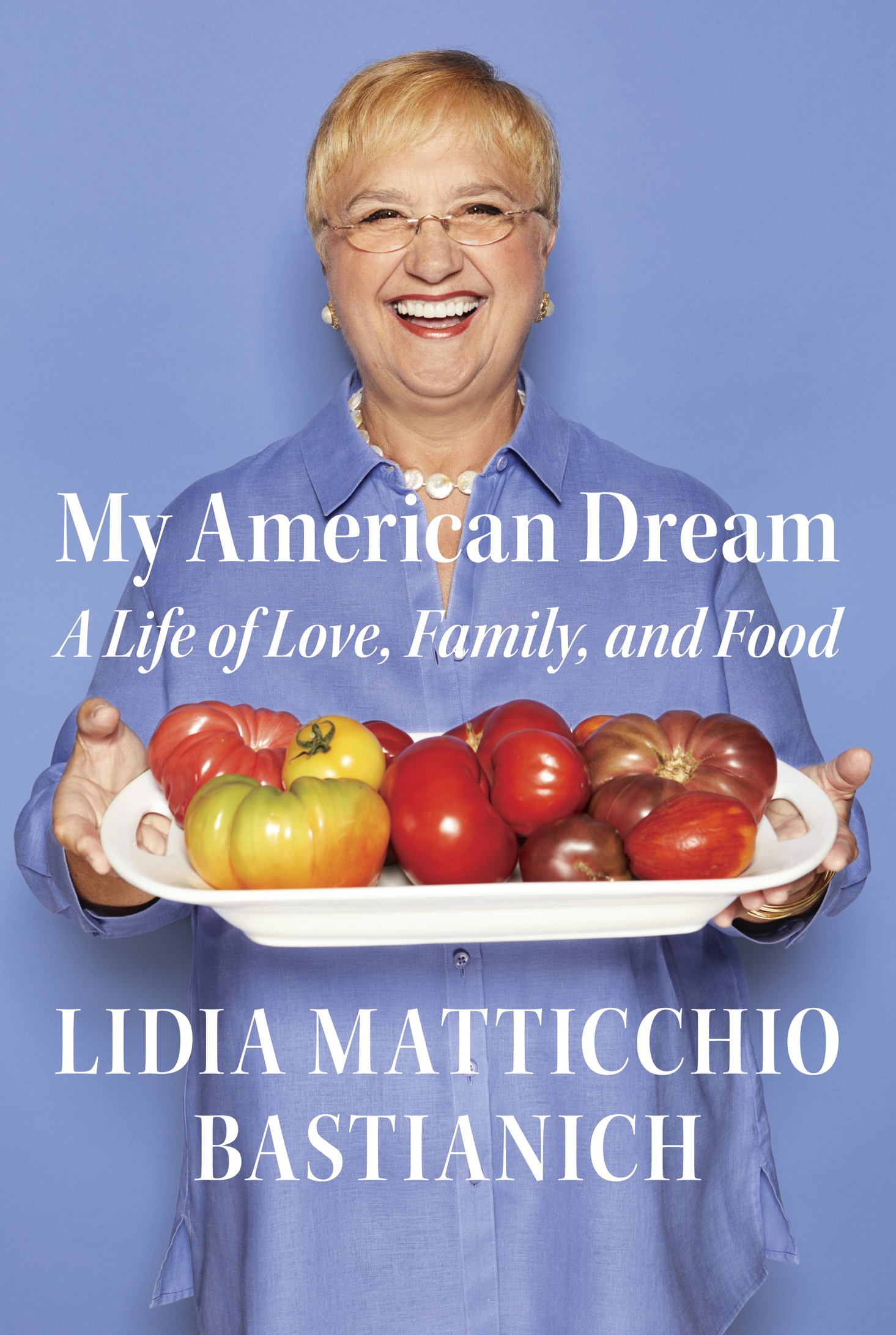

Title: My American dream : a life of love, family, and food / by Lidia

Matticchio Bastianich.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2018. |

This is a Borzoi Book.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017045478 | ISBN 9781524731618 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH : Bastianich, Lidia. | CooksUnited StatesBiography. |

Cooking, Italian. | World War, 19391945RefugeesIstria (Croatia and

Slovenia)Biography.

Classification: LCC TX 649. B 38 A 3 2018 | DDC 641.5092 [ B] dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017045478

Ebook ISBN9781524731625

Cover photograph by Melanie Dunes

Cover design by Kelly Blair

v5.2

ep

To my five precious grandchildren, Olivia, Lorenzo, Miles, Ethan, and Julia. This book is the story of your great-grandparents and their children. You are the products of my mothers and fathers hopes and dreams for a new beginning. You have my unconditional love and blessings. Go forth, flourish, and help keep this great country of ours ever greater. Our life here began as Italian immigrants but we are now all proud Americans.

Contents

1

Giuliana

Few people outside of my immediate family know this, but for the first five years of my life, my name was not Lidia, it was Giuliana. My mother had chosen this name for me as a way to remember her homeland, which was then part of the FriuliVenezia Giulia region of northern Italy. The Second World War had ended, and communism was coming to Pola, the small city on the southern tip of the Istrian Peninsula, overlooking the Adriatic Sea, where my family lived. The Yugoslav Partisans, who were communist-led, had fought as guerrillas against the Nazis and Fascists and had taken over the government of Yugoslavia when the Germans were defeated. As part of the 1947 Treaty of Paris, our city, and most of the Istrian Peninsula, which had become part of Italy after World War I, was given to communist Yugoslavia.

The redrawing of borders sparked a mass exodus from the area, with more than three hundred thousand people fleeing to Italy to reclaim their Italian citizenship. Many of them had deep Italian roots; they spoke Italian, and their families were Italian. Many of them migrated on to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States. My parents planned to join the migration, but my mother was pregnant with me, and they knew that travel would be difficult. There was also the question of where to go once we crossed the border. Refugees were being placed in camps, and my father was not comfortable with the idea of my mothers giving birth and caring for an infant in such a place. They also had my three-year-old brother, Franco, to consider. The war was still raging when my mother gave birth to him in July 1944. With the collapse of Fascist Italy in 1943, the Germans occupied the city and used it as a U-boat base, making it a target for Allied bombardments. The family had no money for clothing or food, much less furniture, so my mother fashioned a cassetta, a wooden cradle, for little Franco from a spaghetti box marked with the word fragile on two sides, and she fitted it with a mattress of corn leaves. When he was five months old, two bombs were dropped on Pola. The minute the siren sounded, alerting residents to the bombardment, my father assumed his role as driver of the fire truck for the Pola town arsenal, Cantiere Navale di Scoglio Olivi. My mother awoke to see pieces of the ceiling falling onto her babys cradle, and she hurried to his side, grabbed the spaghetti box with Franco inside, and ran to the bomb shelter.

At the end of the war, Pola was under the Allied forces when my mother became pregnant with me. The exodus of the Italian Istrians was still open, and many of my mothers friends and relatives were moving to Italy, because Istria was soon to be under the Yugoslavian rule. Food was scarce, and jobs were scarcer.

Still, my mother was an Italian schoolteacher and had the possibility of finding a good job somewhere in Italy. Her supervisor had requested a teaching position for her in Brescia, a city at the foot of the Alps, between Milan and Venice. The position supposedly included housing, so my father loaded all of the familys furniture onto his truck and traveled there to set up what was going to be our new home. He was lucky he had a truck. Many of the optantiopters, people who had opted to leave Istrialoaded their belongings, packed in crates and boxes, onto trains. Some would go toward Trieste, Italy, the Free Territory, their horse-drawn carts with piles of pots, pans, chairs, tables, and other furniture as high as the carts could handle. I recall the stories that my grandmother Nonna Rosa would tell me about how some of those optanti had even dug up the bones of their deceased from the cemeteries and took them along in boxes. They could not bear to leave their loved ones behind.

When my father got to Brescia, he found that the promised apartment was nothing more than a single room, much too small to accommodate our growing family, and a search of the area for available housing turned up nothing suitable or affordable. My father could not bring his pregnant wife and small son there, so he returned home after one week; he still had all of our furniture loaded in the back of the truck. He told my mother the family would remain in Pola until after she gave birth.

That January, my parents went to the pier in Pola to bid farewell to friends boarding the Toscana, a ship full of optanti, for the short voyage to Italy across the Adriatic, headed for Venice and Ravenna; my mother, now eight months pregnant, was teary-eyed and shivering in a coat that barely covered her belly. One month later, on February 21, 1947, she gave birth to me at the hospital in Pola, and seven months after that, on the fifteenth of September, the day the provisions of the Treaty of Paris were put into place, the border between Italy and Yugoslavia was officially closed. My parentsand Franco and Iwere now stuck in Yugoslavia.