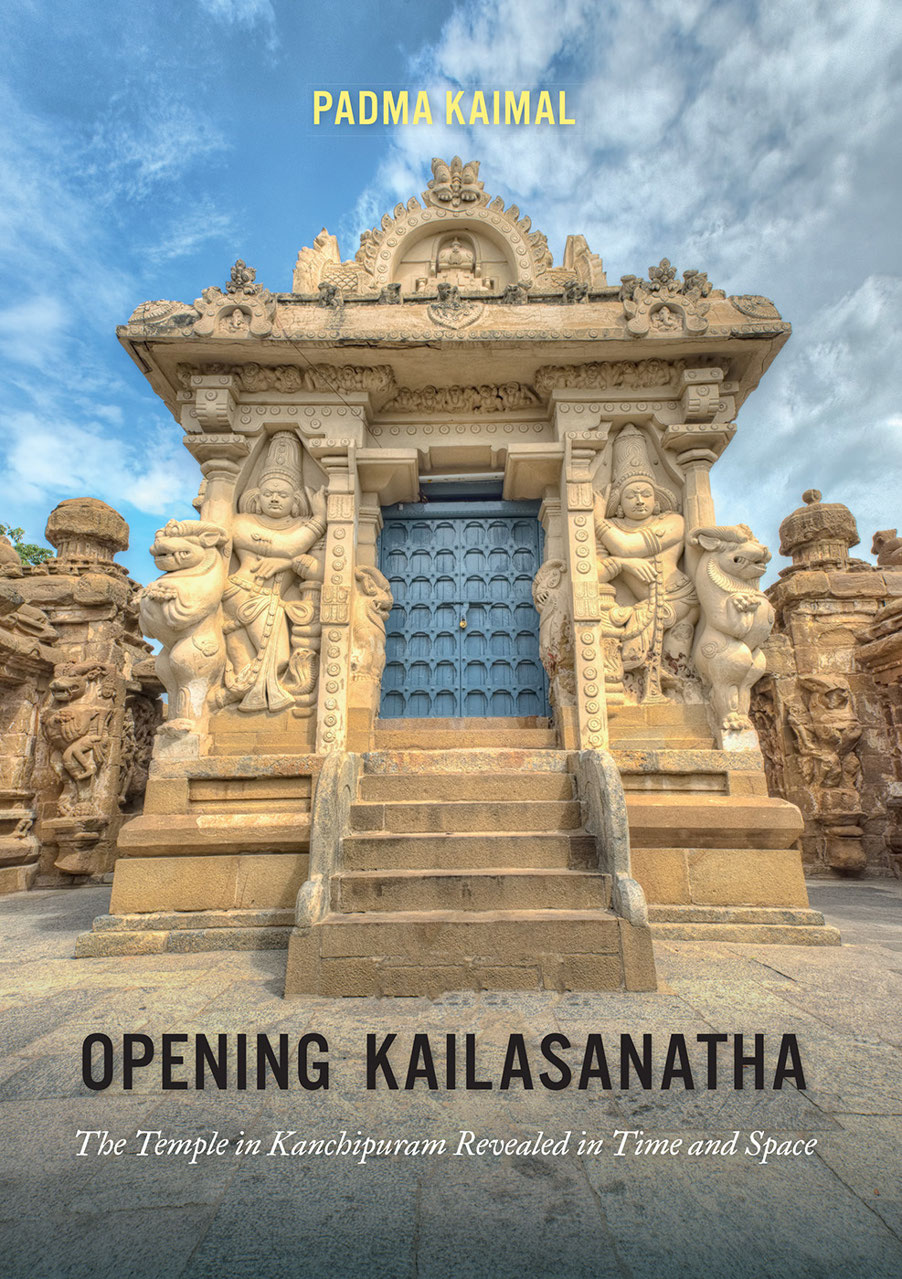

OPENING KAILASANATHA

OPENING

Kailasanatha

The Temple in Kanchipuram Revealed in Time and Space

PADMA KAIMAL

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

Seattle

Publication of Opening Kailasanatha has been aided by a grant from the

Millard Meiss Publication Fund of the College Art Association.

This book was made possible in part by a grant from

the McLellan Endowment, established through the generosity of

Martha McCleary McLellan and Mary McLellan Williams.

Additional support was provided by grants from the Colgate University Research Council,

Office of the Provost and Dean of the Faculty, and Michael J. Batza Chair in Art & Art History.

Copyright 2020 by the University of Washington Press

Design by M. Wright

Composed in Adobe Text, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

25 24 23 22 215 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information

storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

uwapress.uw.edu

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONTROL NUMBER: 2020932709

ISBN 978-0-295-74777-4 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-295-74778-1 (ebook)

Interior photographs are by the author unless otherwise noted.

The paper used in this publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of

American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper

for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.481984.

To Andy, Sophie, and Phoebe, my darlings, my heroes

CONTENTS

Inscriptions on Rajasimhas Prakara

The Foundation Inscription of the Rajasimheshvara,

Rajasimhas Vimana

The Foundation Inscription of the Mahendravarmeshvara,

Mahendravarman IIIs Vimana

The Foundation Inscriptions around Vimanas C, E, and G,

Marking Donations by Pallava Queens

PREFACE & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS BOOK COULD HAPPEN BECAUSE MANY PEOPLE GAVE ME THEIR TIME, insights, expertise, encouragement, and funding. Listing all of those people here is a challenge I am likely to fail, and for this I am very sorry. But I am deeply grateful to everyone who interacted with me over the past twenty-five years about the Kailasanatha temple complex in Kanchipuram. All of you have helped me to think out these ideas and to have the luxury of time to write them down.

Long before conceiving this project, I received a Junior Fellowship from the American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS) thanks to Joanna G. Williams. That gave me my first chances to visit the Kailasanatha in 198485. P. Venugopala Rao, head of the AIIS Madras office, and his assistant Perumal made my research year a success by gracefully navigating many bureaucratic waters for me. The invaluable support of the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Board as well as the Archaeological Survey of India enabled me to photograph and study this and many other sites.

Overwhelmed on my first visit by the visual wealth of the Kailasanatha, I wandered through it for hours and wore out the patience of my bicycle rickshaw driver. I had come to look at a few potential portraits, but I left convinced that the temple complex deserved someones sustained attention. I could not yet imagine it would be mine.

My dear friend Dennis Hudson gave me the courage ten years later to think that that someone might be me after all. His own study of the Vaikuntha Perumal temple in the same city made a convincing case for that temple having been designed as a kind of response text to the Kailasanatha, though exactly what this earlier building meant still remained puzzling to us both. He helped me get started. As we talked about cave temples, he taught me that directionality is the most likely principle organizing the placement of sculptures on temples in the Tamil region. And he collaborated with me to produce a pair of papers on the Kailasanatha for the 1996 symposium of the American Council for Southern Asian Art. We focused on the tall-towered vimana at the center of the compound. I speculated that its sculptures of Shiva embodied ideals of kingship. Dennis engaged the inscriptions astonishing revelation that a king had taken initiation into a Tantric sect. David T. Sanford and Michael Rabe were among the most energetic colleagues to respond to our papers. David cracked open for me the identity of Jalandhara as the defeated figure at the center of the north wall.

Dennis would live just long enough to complete his study of the Vaikuntha Perumal. I then pursued the Kailasanatha project without him. Generous fellowships from the American Association of University Women and the National Endowment for the Humanities gave me three semesters of leave from teaching in 20012 that let me immerse myself in literature on goddess worship in South Asia. I began to see that goddess imagery played a larger role at the Kailasanatha than most scholarship on that monument had led me to expect.

Major grants from the Colgate University Research Council permitted me to return to the site in 1999 and 2010. South Asia scholar Kimberly Masteller; her husband, Donovan Dodrill; and my parents, Lorraine and Chandran Kaimal, joined me at the site in 1999 for delightful conversation, study, and photography. Kim brought her expertise on goddess temples. Donovans sharp eyes caught the small sculptures of Shiva as a meditating ascetic on the tiny towers over cells 1529 of Rajasimhas prakara.

That tour got me thinking about that prakara as a kind of goddess temple in its own right, a hypothesis I shared at the 2001 conference of the American Academy of Religion and then in its journal. Leslie C. Orr organized both projects, bringing me together with Corinne Dempsey, Whitney Kelting, and Richard Cohen in challenging the alleged marginality of goddesses in South Asian practice. I was able to continue workshopping that thesis and other thoughts about the monument with scholars and wider audiences thanks to speaking invitations from Rebecca Brown at St. Marys College of Maryland, 1999; Rob Linrothe at Skidmore College; Vivien Fryd at Vanderbilt University; Michael Cothren at Swarthmore College; Margaret Supplee Smith at Wake Forest University; Susan Mann, Deborah Harkness, and Karen Halttunen at the University of California, Davis; Adam Hardy at De Montfort University, Leicester, England; Rick Asher at the University of Minnesota; Donald Wood at the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama; Indira Peterson for a symposium at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Janice Leoshko at the University of Texas, Austin; Charlotte Schmid at the cole franaise dExtrme-Orient (EFEO) and Emmanuel Francis at the Centre dtude de lInde et de lAsie du Sud; Nicolas Dejenne at the Universit Sorbonne NouvelleParis 3; and Elizabeth Cecil at Brown University. At each place, lively questions from colleagues and audiences flushed out my weaker assumptions and pressed me to interrogate the monument more closely.

By 2009, I had a clear vision of the published record and the many parts of the monument, but I did not yet have a compelling story to tell. I had pieces, but they did not add new insights about the whole. That changed when I had the great fortune to spend 201011 at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) at Princeton University as the Louise and John Steffens Founders Circle and the Starr Foundation East Asian Studies Endowment Fund Member. The time to think, read, and write was wonderful, but more precious were the guidance, the hard questions, and the fascinating conversations I had with the faculty and other members. I must extend particular thanks to Yve-Alain Bois, Caroline Walker Bynum, Nicola Di Cosmo, and Irving and Marilyn Lavin on the faculty; Marian Zelazny on the IAS staff; and fellow IAS members Norman Kutcher, Daniela Caglioti, Katrin Kogman-Appel, Menachem Kojman, Mehmet-Ali Ata, Toni Bierl, Eleonore Le Jalle, Richard Taws, and Himanshu Prabha Ray. Mehmet-Ali transformed my understanding of how art can represent time and convinced me that reducing the past to the political does an injustice. Toni encouraged me to pursue evidence of complementarities in place of binaries by sharing his own parallel discoveries in ancient Greek materials. Himanshu urged me to consider the buildings marginal sculptures as spaces in which individual artisans had room to improvise on underlying themes. At the Lavins suggestion, their friend Frank Gehry stopped by my office to look at my photos and observe that the Kailasanatha, like his creations, was a building that could produce the illusion of movement.