Independence is loyalty to ones best self and principles.

Mark Twain

A changed world

Why do we travel? Is it to see iconic places, to visit friends and family, to break the routine, to learn, to have fun, to be pampered, to shop? Yes, certainly, it can be for all these reasons. It might be to tick off an item on your bucket list, to collect anecdotes for dinner parties, or to take the perfect Instagram shot. Or maybe its because we have all the possessions we need and are looking for another way to spend our money. Or that the grass always seems greener somewhere else.

Is it because we are easily swayed by the marketers who tell us that we are lesser beings without a passport full of stamps? We want to believe that we are capable of making up our own mind rationally, but the reality is our decisions are mostly emotion-based and groupthink often has the stronger say.

Maybe it is that we give little thought to our reasons for travel. We simply pack our bags and go.

Or at least we did, until our jet-setting ways came to an abrupt halt in 2020 and we looked, amazed, at photographs of blue skies over Beijing and fish in Venetian canals. Despite the economic disaster of lost tourism income, the tortoises of the Galapagos Islands must have breathed a sigh of relief. Streets stripped bare of visiting hordes opened the way for new relationships between residents and their cities.

These positive changes gave us real pause for thought and inescapable evidence of the negative impacts of travel. They turned our minds towards the opportunities and virtues of staying home.

Weigh up both sides

Until recently, travel wasnt for everyone. There were pilgrimages, merchant voyages and Grand Tours, but most people lived their entire lives within the boundaries of their village, town or city. They might have ventured to the next town within walking distance, for matters of trade, but holidays were holy days and their observance was centred on home, church and the market square.

Perhaps its our eras wealth and access to cheap and easy transportation more than inherent wanderlust that sends us on our journeys.

While the internet is awash with all the positives about why we should travel, there have always been dissenting voices. Ralph Waldo Emerson said it brought ruins to the ruins. And Marcel Proust wrote that, the real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.

Like many others, Paul Theroux was at pains to apply a measure of status by distinguishing travellers from tourists (travellers being trailblazing adventurers, tourists mere followers). While the American journalist Elizabeth Drew noted that travel was more likely to lengthen conversations than broaden minds.

The debate has washed back and forth. The phenomenal growth in tourist numbers has made us ambivalent towards travel, as weve become more aware of the damage our travels have unwittingly inflicted on host communities, natural environments and, indeed, the planet.

How should we live?

Has our pursuit of the good life, with its attendant wealth and consumption, made us blind to what is most important? Have we forgotten to ask ourselves how we should live in a way that is most likely to achieve meaning in life?

In searching for an answer we might examine the way in which travel can crowd out what really matters: home, belonging, relationships. We might also ask, in terms of contemporary concerns and obligations: How should we live in these times of uncertainty and rapid change? How should we live in ways that minimise damage?

We might more honestly examine travels downsides. It can be lonely, uncomfortable, fatiguing, tedious and disappointing. It can, on occasion, be frightening. And what of the financial strain? Most people identify financial concerns as the major cause of their stress and acknowledge that the best coping mechanism is adjusting expectations.

It is within ourselves not out in the world where we must find our answers. Independent-mindedness is the key to deciding what is best for us and resisting the social and commercial forces that try to control our choices. In place of consumption we can choose contentment, acceptance, gratitude, with who we are, what we have, and how we live.

Finding home

In the 1920s American writer Henry Beston spent a year living alone on an isolated stretch of the Maine coastline. In the book that he wrote of his experience The Outermost House: a Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod we follow him through the seasons and through his ever-growing affinity with his remote home as he observed and recorded the world constantly changing around him.

He wrote of storms more fantastic than fireworks displays and of the surfs world of sounds. In this one place his home he showed what is gained when we engage our five senses, how the tiniest details open up new vistas of understanding. Everything weaves together into a whole that becomes a sense of place. The deep and satisfying attachment that can only be achieved by taking the time and making the effort to be acutely attuned to ones surroundings.

As this was the 1920s Beston wasnt observing his world through a smartphone, nor did he allow his vision to be constrained by the lens of a camera. He committed to memory what he saw through his naked eye, then put what he had observed into words. Reading those words a hundred years later we relearn what we have forgotten. We discover ourselves through our sensual experience of what is immediately around us. This is how we connect to a place and come to know who we are.

We are shaped by where we live. The external becomes internal. This is what John Steinbeck discovered when he drove across the United States with his dog Charley in an attempt to find what it meant to be American. In his book Travels with Charley, he explained how America revealed itself to be a larger version of himself. And only he, as an American, would see his homeland in this way. People from other countries could make the same journey, but their interpretations of what they saw and heard would be completely different.

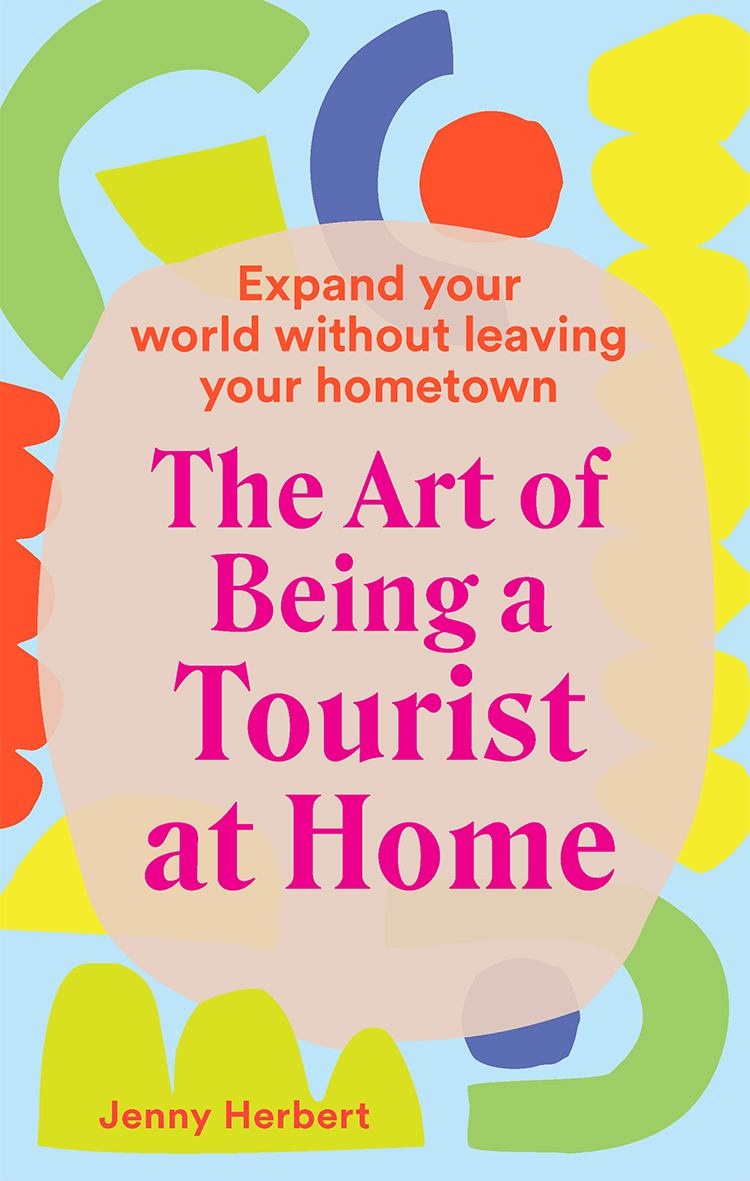

Where to begin?

Well start our exploration of home by putting into practice, locally, the sort of activities we undertake when far away. Walking unfamiliar streets, paying attention to detail, visiting parks and gardens, and meeting people of different nationalities. Well discover how all of these activities can be easily pursued close to home, with the same or greater rewards. Well challenge the myth that we should and must travel.

Two or three hours walking will carry me to as strange a country as I expect ever to see.

Henry David Thoreau

Look again

Years ago, on a Sunday morning in Rome, I rose before dawn and went for a walk in what might have been a completely different city. No traffic, no noise other than church bells ringing and pigeons cooing. I passed only a few people: drowsy carabinieri in the Piazza del Popolo; couples with linked arms on their way to early Mass; waiters setting up outdoor tables. They each offered a quiet buon giorno. The city belonged to them alone.

The Trevi Fountain and Spanish Steps were deserted; the churches were the preserve of a few parishioners. I strolled wherever my steps took me and watched the grand metropolis come slowly to life as cafs opened, traffic built, and the Via del Corso filled with shoppers. It was a rare experience and all it took was a walk at an uncommon time of day.

Next page