An Introduction

If you let yourself be blown to and fro,

you lose touch with your root.

Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching; transl. by Stephen Mitchell

Im sitting on the old footbridge that leads to my cabin in the woods. Beaver Creek passes silently below. Ducks fly overhead. Ferns, cardinal flowers and moss grow amid grey rocks at the waters edge. Spiders wander over my notebooks, which are spread out on the bridges rough planks, pages held open by stones.

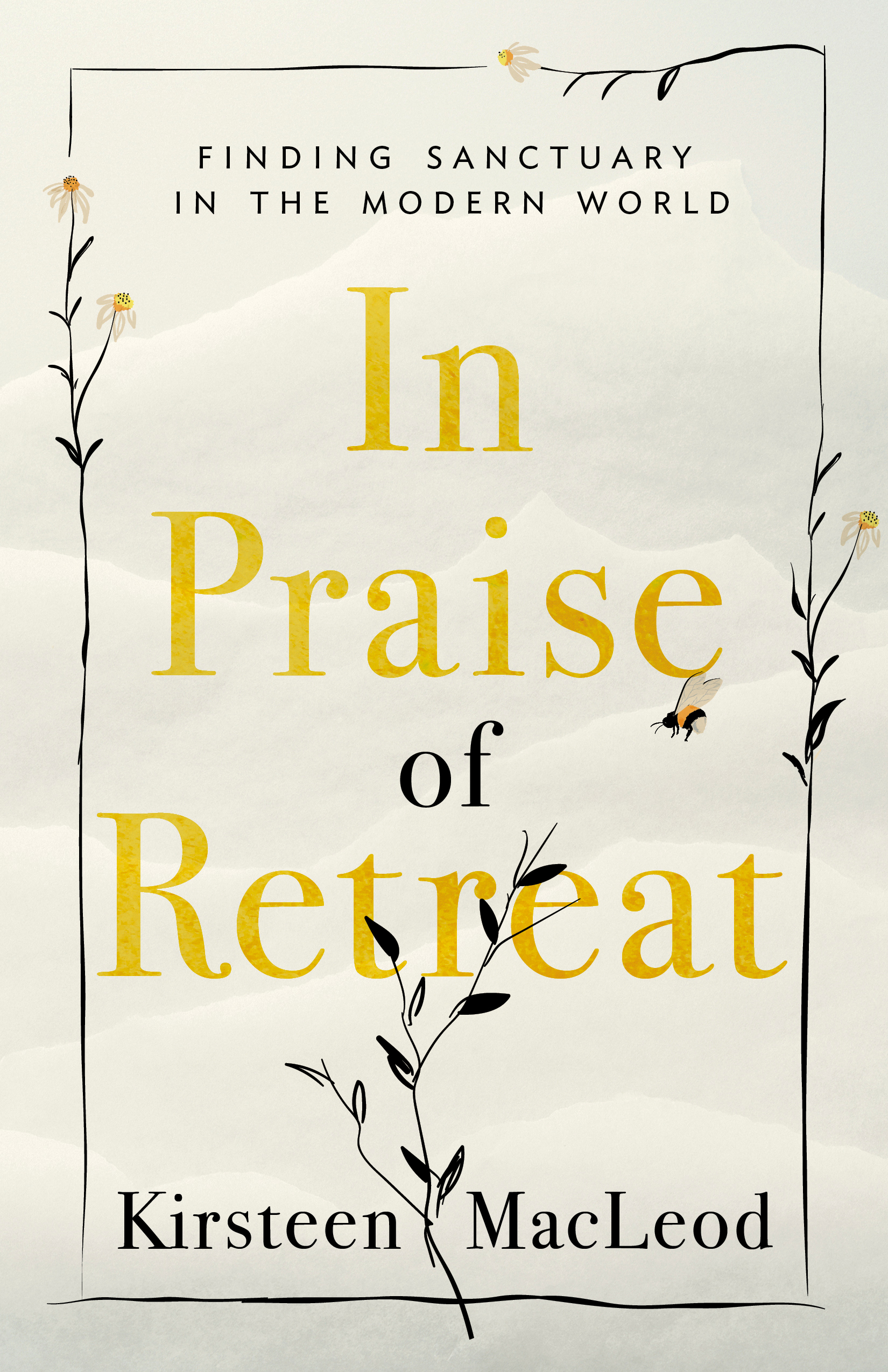

This is the place that inspired this book. By the creek and in the forest, I discovered a rich inner dimension I didnt know existed. Far from my city life and work-obsessed routines, I began to see what gives my life meaning. I recognized the value of protecting a divine spark, though Im not religious, and of amplifying the extraordinarynature, spirit, art, creative thinkingin impoverished times. A retreat means removing yourself from society, to a quiet place where moments are strung like pearls, and after long days apart spent in inspiring surroundings, you return home refreshed and with a new sense of what you want to do with your life.

In the fraught modern era, youd think our timeless human desire to retreat would feel more urgent than ever. Yet taking a step back has become an act of 21st-century rebellion when disengaging, even briefly, is seen by many as self-indulgent, unproductive and anti-social. But to retreat is as basic a human need as being with others. To withdraw from the everyday is about making breathing space for what illuminates a life.

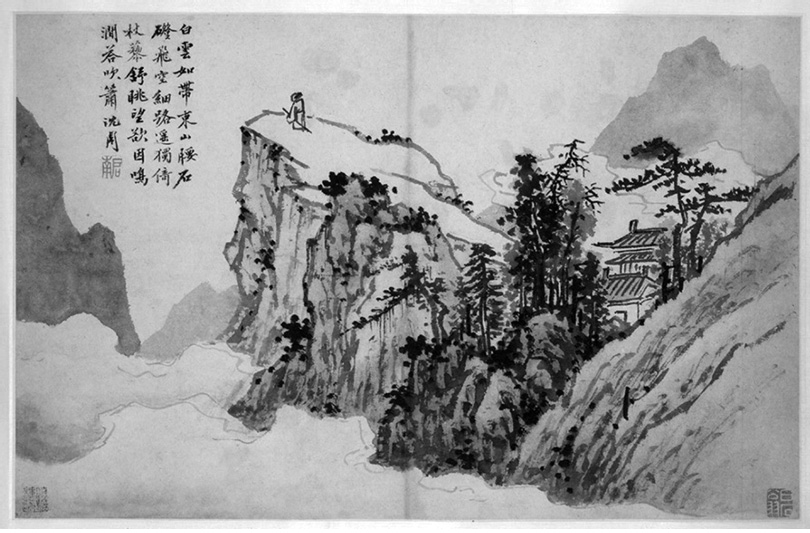

For millennia, people have retreated from human concerns as a corrective, spiritual and otherwise. This is a universal impulse, evident in all times, in all cultures. Throughout history, opinion has swung between two poles on the question of how to find fulfillment in lifein solitude, or in society? In the sixth century BC, when early philosophies for a good life dawned in China, Confucius said the key was to meet ones social obligations. Lao-Tzu said the key was to avoid themthough his teachings show that he cared deeply for fellow humans, and for the natural world.

Lao-Tzu left few traces, and even his name is uncertain; likely translations include the Old Master or the Old Boy. He fled corrupt court life, legend has it, through the western mountain passes of China, disguised as a farmer and riding a water buffalo, or a blue ox, or a black ox, depending on the source. The sage was supposedly recognized by a border guard and asked to share his wisdom before he departed. Lao-Tzu dictated the Tao Te Ching and then disappeared, likely to become a hermit. The Book of the Way, as its known in English, imparts its lucid counsel about living a self-directed life and has inspired kindred spirits ever since, including the Sage of Concord, Henry David Thoreau.

In the 21st century, when we over-venerate the active and the social, I find myself in deep sympathy with the Taoist philosophers of antiquity, who viewed the universe as a flux of paradoxical opposites. Early terms they used to describe this were the firm and the yieldinglater referred to as yang and yin. Visually, this indivisible unity is represented by a circle, half light and half dark, each containing a dot of the other shade. The idea is that energies are in interchange, universal energies from which everything emerges, and their dynamic balance brings cosmic harmony.

Contrary to Western dualism these opposites are not at war but hold equal importance, permeate one another, and create a whole. The world of being arises out of their change and interplay, explains Richard Wilhelm, who translated the I Ching, or Book of Changes, into German in 1924, thus opening up the spiritual heritage of China to the West. The I Ching is the common source for both Taoist and Confucian philosophy and was first published in English in 1950.

Westerners may consider such concepts esoteric or mystifying, but they are common in the East. And common sense, I believe. It seems logical that we need action and engagement, yang energy, and also the complementary yin, which is solitary, reflective and receptive. This does not mean passive, as its often misinterpreted in the West. Wei wu wei, or effortless effort, describes yins power, observable in the action of a river on rock. To quote the Tao Te Ching, written between 300 and 600 BC: Nothing in the world/is as soft and yielding as water./Yet for dissolving the hard and inflexible,/nothing can surpass it.

Similarly, to retreat is about widening our perspective, about the pursuit of the whole, developing yin attributes rather than rejecting them. In a historical time when solitude and silence are conflated with boredom, and no one wants to be seen as a weird loner, retreat has become a countercultural notion. I admit to being irritable about this. I believe independent people like solitude, and retreating is healthy for everyone at particular times of life, for particular reasons. A retreat is different from a holiday: its a temporary, voluntary withdrawal from everyday life for a purposefor personal, social, environmental, spiritual, artistic or even professional reasons. Its about deep engagement and, often, dissidence.

Granted, not everyone wants to flee permanently through the Han-Ku Pass as Lao-Tzu did, or has the means to do so, including me. Thats why over the past 20-plus years I became a serial retreater, creating islands of space and time, a week here, a month there, to answer a faint call, barely heard above the din of the everyday: There must be something morewhere can I find it? One good retreat led to another, and slowly, my life transformed.

Retreat is an adventure, and it involves uncertainty. Whether we go to the quiet woods to rest or make art, walk a pilgrim path or sit in silent meditation, were in some way seeking a new way to be. Were creating space for change.

Im not dismissing ordinary, active, social life and its routines: thats how we keep the lights on, the dog fed and the world turning. No one needs reminding of the value of the everyday, or of relationships and work. But I believe we have mistaken this half of reality for the whole. As modern times sweep away the extraordinary, the transcendent and our attention, retreat offers a way to reclaim whats being lost. Like many people, I dont want to be blown about by the wind, always in company. I have other priorities, which is where retreat comes in.

I have often wondered why I am so interested in retreat and its yin companions, solitude and silence. This book is my chance to consider the question, for myself and everyone else who wants to inhabit a slower, quieter, more thoughtful world than the 21st century usually offers. Drawing on my own experiences, and the wisdom of hermits, monks, pilgrims, naturalists, writers and artists, solitary thinkers and other independent spirits, living and dead, I will explore the art of retreat and how it can reconnect us to our essenceand why this is a matter of urgency for personal and planetary health in modern times.